Paul Cullen

Provisional Arrangements

10 February - 11 March 2017

Paul Cullen’s Two Rooms exhibition is a modified version of the original Provisional Arrangements exhibition presented in June 2016 in the Ilam Campus Gallery in Christchurch. The studio rehearsals for these exhibitions, which he and I jointly conducted in Henderson, like duettists in an improvised pipe-organ recital, felt like an extended slow/fast game of clattering sticks and moveable furniture – centred on the tautological doubling of mobile moveables.[1]

The process was like arranging and re-arranging components on a room-size gaming board whose markings and rules we could never entirely figure out. Or having a whole day in a street blocked from through-traffic to set up tables and chairs, blankets and plants, for indoor bowls and a nocturnal dinner party. Or extending the green crystal grit of an Auckland bus lane across all of the street so we could drive on a very long inner-city tennis court. Or designing a ‘fabricated terrain’ for objects as actors, like the rooftop outdoor–indoor–lawn–living-room that Le Corbusier designed for Carlos de Beistegui’s Paris apartment and initially planned as a walled croquet field. Or making a rooftop model in a low-sided tray for a bookshelf, like Le Corbusier’s wood-and-plaster model for the top of his Unité d’habitation apartment block, the rooftop of which did resemble a playground of small buildings and sculptural forms piggy-backing on the bulk of the building beneath.[2]

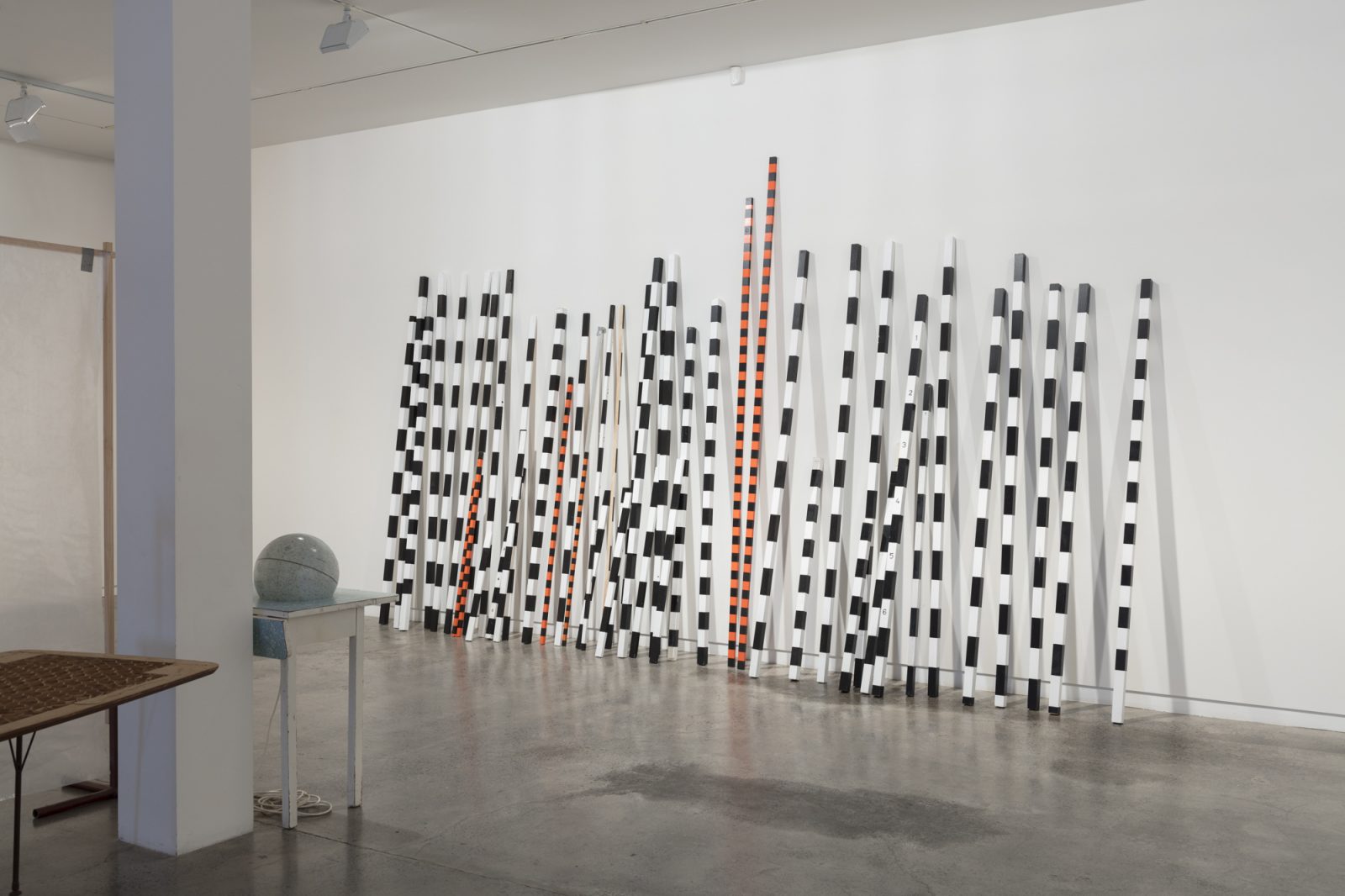

Cullen’s concrete studio floor became a support surface for a multipart apparatus in degrees of disarray or resolution. The portable parts were configured differently as bundles of striped sticks, concrete cylinders and stubby cones trailing rope fuses, misconstrued furniture and clamped-on lower-limb table orthoses, projection-screen metal skeletons and plaster-cast books, were pushed around, stacked, leaned, and variously disposed against walls or in long islands of thing-lines in the space available. Map-like images of a fifty thousand-year-old crater site, an archaic index of catastrophe looped by tracks, presided over the place-trading business of things going on in the studio around them – the articulation / disarticulation of an accented materiality in which everything fitted together by not quite fitting.

Once again, I was in the imaginary of those part by part, stick-stutter, shutter-stutter freeze-frame metonymies of early and present-day modernism, which we shaped and which shape us as alliteratively rhythmic bundlings of articulated segments. From the sectionalised fans of animal profiles in motion shot by Marey’s camera gun, to Muybridge’s proto-cinematic locomotion discontinuities of women step-hopping over chairs, to Charlie Chaplin’s splay-footed waddle, to Little Nemo’s wooden bed flying into pieces as he catapults into space through the conjoint windows of Winsor McCay’s comic strip, to Rilke’s cane-carrying war veteran self-hyphenating into ‘that compulsive two-beat rhythm’,[3] to the noisy rebellion of rafters, purlins, cross-beams and wooden trestles in Bruno Schulz’s The Street of Crocodiles, up to John Panting’s chopped-off thickets of steel bar and strip, Rachel Harrison’s cross-hatched barricade of sawn struts on trolleys, Georg Herold’s roof-batten bony figures with lacquered fabric skin, a Paul Eachus staged studio avalanche of shards, Jason Lindsay’s shattered screen of sticks and skewed plywood geometries, and Richard Reddaway’s spindly Rietveld constructions with mirror-tile mosaic trim.

Not only did Cullen once earn his living repairing furniture, he has spent years working with splinted and braced tables and chairs, ad hoc plumbing fantasies, and with motorised objects, including globes, plastic fruit and angular planets covered in foil. He has become a fabricator and deconstructor of apparatuses, activating and laying bare the prosthetic device wherever he can. The secret worlds of apparatuses that Cullen lays bare look intermittent, incomplete, faltering, misaligned and only temporarily effective. And, just as habitual cycling leads to an exchange of properties between the cyclist and the bicycle, to the extent that life-cyclers can often be found leaning with one foot propped on the kerb, according to the police sergeant in Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman,[4] so Cullen, with his own walking stick now – necessary correction, prosthetic feature marking an interrupted gait – has become more like his art than he had anticipated. He also now lives mid-city, adjacent to a roof garden with a giant chess set, some potted plants and assorted outdoor furniture, and owns his own power-assisted bicycle – rolling displaced exoskeleton, insectile motorised support structure on wheels. Through the spoke streaks of Cullen’s power bike I hear Clark Coolidge chanting: ‘I believe in thresholds, faucet handles, and brads./I believe that we are determined by broken spaces and broken times.’[5]

‘What is an apparatus?’ asks Giorgio Agamben in his essay on Foucault’s use of the term.[6] An apparatus is a type of provisional arrangement really. It’s a set of things linked through a shared task or purpose. Something or some set-up at work, a related group of things, procedures and rules enlisted to perform a particular operation. An apparatus works by co-opting a variety of parts from their general business in the world to converge on a particular project. An apparatus may be a composite object with all its synchronised parts aligned inside a box or casing, such as a camera or an electric blender; or it may be a surrealist relay of objects whose congress occurs through tubes, pipes, and taps across tables, as with one of Marie-Anne and Antoine Lavoisier’s eighteenth-century experiments to observe the chemistry of deflagration combustion; or it may be a compilation of market algorithms, information technology networks and policy statements which structure and support the operation of a corporate finance company.

Given that an apparatus supposes an economy of means with particular goals in sight it is troubling, says Agamben, that contemporary societies, characterised by ‘a massive accumulation and proliferation of apparatuses’, experience the operation of apparatuses large and small as the ‘pure activity’ of organisational means ‘that aim at nothing but [their] own replication’.[7] In terms of the governmental apparatus we witness ‘the incessant though aimless motion’ of this omnipresent machine. There is a strange rapport between modern and contemporary art practices that import the means and methods of organisational systems from outside the field of art, as portable rhetorics that can be abstracted from their original contexts, and the aimless self-replication of the well-functioning governmental apparatus. Such rhetorically and methodologically parasitic art reiterates the foundational lacks and anxieties of modernism. No longer underwritten by shared mythological, religious or political projects, modern art constantly searches for organisational paradigms around which to structure itself. Divorced from any functional necessity and aestheticised for relocation, such definitional languages are always hollowed out in advance.

Like the giant eyes of Dr Eckleburg’s glasses watching over their valley of ashes in Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Cullen’s meteor-site images in the current show stare blankly at the artist’s constructional mannerisms. Cullen’s repeating ancient-disaster images augment and scale up the host of tiny crises signified by each accentuated displacement, proud joint and welded seam, all the nervy staccati of battens and rods, all the material disjunction that shuttles and shuffles its way through the installation’s assembled parts.

Art practices that pursue languages of material disjunction, incompleteness and methodological opacity can seem to silhouette the intractable fabrications that piece our social and imaginary realities together. Being reminded of how our lives and institutions are constitutively riddled with gaps, blocks and obscure mechanisms is both disconcerting and exhilarating. Such practices can promise purchase on the oppressing weight of the world and the fixities of its structures, as well as constantly bring us back to the failings and concrete limits of our bodies, to the physical specifics through which we must thread our speculative dreaming and conceptual schemes.

– Allan Smith, curator

- The French distinguish between furniture as meubles, movables, and buildings as immeubles, immovables.

- For Le Corbusier’s term ‘fabricated terrain’, and images I allude to, see Jacques Lacan, ‘The Search for The Absolute’, in Carlo Palazzolo & Riccardo Vio (eds), In the Footsteps of Le Corbusier, Rizzoli, New York 1991, pp 197–207.

- Rainer Maria Rilke, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, trans Michael Hulse, Penguin, London, 2009, p 46.

- The artist is very attached to this book.

- Clark Coolidge, from ‘Hommage to Ballard’, in Sound as Thought, Sun and Moon Press, Los Angeles, 1990.

- Giorgio Agamben, What Is An Apparatus? And Other Essays, trans David Kishik & Stefan Pedatella, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, 2009. [Emphasis added]

- Ibid, pp 15, 22.