Fiona Pardington

An Answering Hark: from the McCahon Artists’ Residency 2013

8 November - 7 December 2013

Fiona Pardington

An Answering Hark: From the McCahon Artists’ Residency

For photographer and New Zealand Art Foundation Laureate Fiona Pardington, to be awarded the 2013 Colin McCahon artist’s residency was a recognition of her significant status as an artist. For New Zealand artists, the painter Colin McCahon’s oeuvre and legacy cast a long shadow that is difficult to get out from under and impossible to ignore. He was, without a doubt, the preeminent New Zealand modernist of the twentieth century, a controversial figure, and is one of the few New Zealand artists that most New Zealanders could name. It is a powerful experience to be working among the same Titirangi kauri that McCahon immortalised with his own unique take on Mondrian.

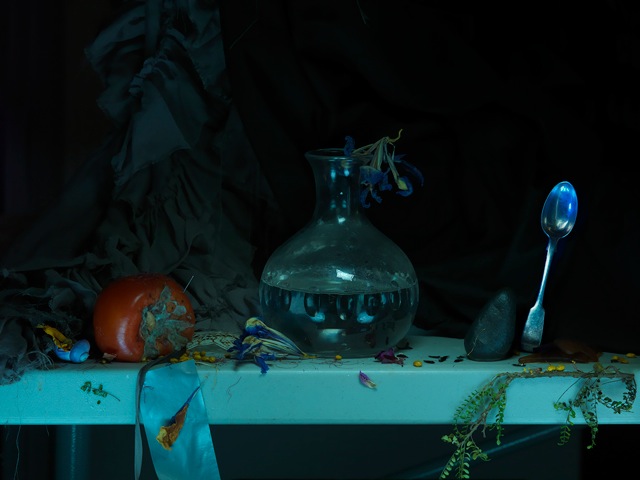

In recent years one of the major areas of focus in Pardington’s work has been the photographic still life – artfully composed tableaux of sentimental, symbolic or otherwise interesting objects, dramatically lit with LED lights. Pardington’s still lifes draw heavily on the European tradition of the vanitas or momento mori painting – the accumulations of vanities and symbols of death that remind us to take life seriously because we too shall die one day. Skulls were a favourite motif, as were wilting flowers and pretty ornaments. Glass was also popular for its fragility and its ability to showcase the artist’s skill in capturing reflection and transparency.

One of the challenges that Pardington faced was bringing McCahon and the residency into the work in a way that was authentic without feeling forced or trite. Working in his old house created a sense of empathy with him – the pressures of making art and the pressures of family sharing a small space, the intense introspectiveness of art-making, and the precarious balance between the domestic and spiritually exultant. To a certain extent the dramatic chiaroscuro and meditation on mortality of the still lifes found a natural resonance with McCahon’s dyspeptic melancholy and the black backgrounds of his paintings. The glassware and candles Pardington has used also seem to suggest McCahon paintings like This is the Promised Land (Auckland Art Gallery, 1948) and A Candle in a Dark Room (Auckland Art Gallery, 1947). For both artists, light is a symbol of spiritual energy.

The presence of the physical location inveigles its way in through many routes. The flowers were sourced from McCahon’s garden – forget-me-nots, the ephemeral pururi gathered by Fiona from McCahon’s own tree every morning before going into the studio – have a difficult but valid presence in the work. McCahon’s personal addictions also have a presence – smouldering cigarette butts in an ashtray as if his shade had been there painting late into the night, the tipple glasses and carafes from the house, the empty flagons he threw into the bush once they were drained of their last drop.

Certain elements are purely Pardington’s own – the dried e-ihumoana (Portuguese man- o’-war), the slave collar and exquisitely gilded dildo (a thread of eroticism extends through most of Pardington’s body of work), a found love letter on a twenty dollar note, silver absinthe spoons, a carved pounamu (greenstone) waka (canoe) representing the divine pounamu boat Arahura sacred to Pardington’s Ngai Tahu ancestors. If Pardington had encountered McCahon’s spirit abroad in the studio one night, the conversation could only have been interesting.

Andrew Paul Wood