Judy Darragh & Sean Kerr

In Kahoots

14 August - 21 September 2019

But the instant-now is a firefly that sparks and goes out, sparks and goes out. The present is the instant in which the wheel of the speeding car just barely touches the ground. And the part of the wheel that still hasn’t touched, will touch in that immediacy that absorbs the present instant and turns it into the past. I, alive and glimmering like the instants, spark and go out, alight and go out, spark and go out. – Clarice Lispector, Água Viva

In Kahoots is a collaborative exhibition by Judy Darragh and Sean Kerr played out in the key of a present-day fable. Encompassing sculpture, real-time animation, video, sound, wall-based collage and digital photographs, In Kahoots draws on Plato’s Allegory of the Cave to locate a shared meditation on collective resistance, transformation and ecstatic revolution. Across the exhibition the artists invoke myth as a means of navigating a contemporary fray and as a method for making sensible the dynamic, circular and present tenses of time.

Time, gathering its threads into thickets, shapes the horizons and ellipses by which meaning is made. Licked by the shadows of future and past, the present forms its contours in the manner of magma or stardust. Pervasive and formless, flickering in a shapeless rhythm, it moves ever further from the mind’s attempts to take hold. In the short fable-theory Thumbelina, the late philosopher Michel Serres speaks to our grasp of this temporal landscape as irrevocably transformed by computation and contemporary technology. Reflecting on the implications this poses for human consciousness and its multitude of imaginaries, Serres writes of the transmission of knowledge and the creative potentials of cognition as now oscillating in an environment radically altered from that of our ancestors. The horizons of both future and past extend to scales that were previously unthinkable, while the speed and scope with which we can access, act, communicate and exchange knowledge in any given instant create a plethora of new freedoms and concerns. The mind’s energy and focus, now liberated from the rote tasks of memory and recall, might invent new purposes, Serres posits. But these conditions also necessitate the creation of pedagogies and story-forms with the capacity to cultivate new connections and empathies. Young urban-dwellers born within the last five decades, he observes, ‘know nothing of the rustic life, domestic animals, or the summer harvest. They have not lived through ten wars, the wounded, the starving, the motherland, bloody flags, cemeteries, or monuments to the dead. Nor have they ever experienced, through their suffering, the vital urgency of a morality. What literature or history will they be able to understand?’2

Serres’s stance is by no measure one of morose condemnation; rather it is a call to, and celebration of, contemporary stories and sensibilities. With a carefully measured paternalism, he looks to a generation with ‘pockets filled with all of the knowledge in their smart phones’. It is their bodies, Serres writes, that are now free to leave the cave, where once they were shackled to the lectern and their seats. The new autonomy of our understanding ‘finds complement in corporeal movements without constraint and a brouhaha of voices.’3

Drums roll in the distance: what shadows through yonder cave-window breaks? Of what present ruptures do the signs now speak? Sashaying between allegory and animistic world-building, Darragh and Kerr follow Serres to the scene of Plato’s primal ‘allegory’ to refigure the cave as a site fit for the return of said bodies and voices. Yet they find it already shaking with the energy and messengers of new movements, already overfull and all a-mingle with the shadow-forms cast by the real fakes, fake reals, deep fakes and algorithmic manipulations of the mediated landscape. The images spark and go out, alight and go out. Yet an invisible rhythm of uprising remains. The mythical cosmic egg cracks open, from Zeus’s splitting headache Athena is born. Classic. They return to the classics, drawing on the sculptural legacy of gesture as bearer of the news.

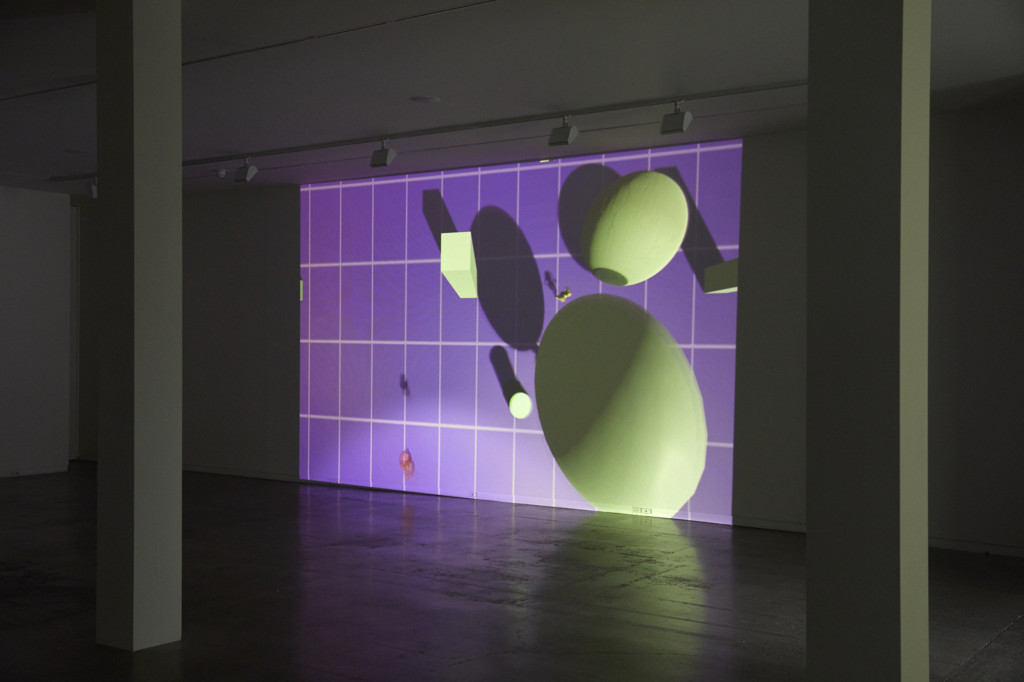

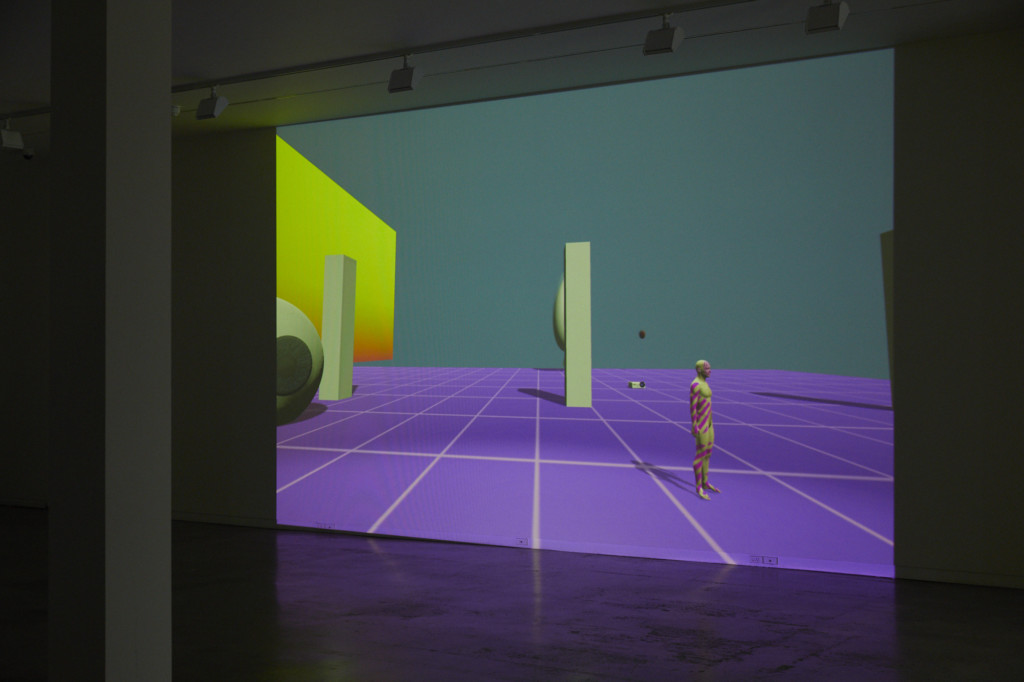

The real-time animation work Sleep on It develops from Kerr’s current research exploring the interactive potential of new media technologies. Built with the gaming platform Unity, Sleep on It sets in motion a self-generating conglomeration of viewpoints and dance routines in a shifting, in-the-present world. Shaped with signature Darragh and Kerr panache, levitating wigs and the ghost of paintings past float among the cave fires of the street-cum-nightclub. A large roving eyeball becomes one gaze among many, ears flex for the sounds of battle cries and beats, figures rework their own scripts and priorities. Bouncing between the rocks of purification and poiesis, revolution and revelry, with their evolving cast of characters Darragh and Kerr hone-in on the echoes and imaginaries of emerging collective bodies with the mirth and generosity that is characteristic of both artists’ practice.

1 Clarice Lispector, Água Viva, trans Stefan Tobler, New Directions, New York, 2014, pp 9–10.

2 Michel Serres, Thumbelina: The Culture and Technology of Millennials, Rowman and Littlefield, London, 2015, p 4.

Judy Darragh and Sean Kerr

Multi media installation, sound projected image Realtime 3D LED, mirror wall

Judy Darragh and Sean Kerr

Multi media installation, sound projected image Realtime 3D LED, mirror wall

Judy Darragh and Sean Kerr

Multi media installation, sound projected image Realtime 3D LED, mirror wall

Judy Darragh,

Mixed media

420 mm diameter

Judy Darragh

Mixed media

Mixed media

400 x 400 x 400 mm

Judy Darragh

Mixed media

600 x 430 x 290 mm

Judy Darragh

Mixed media

950 x 380 mm

Judy Darragh

Mixed media

800 x 800 mm

Judy Darragh

Unique archival digital print

710 x 900 mm

Judy Darragh

Mixed media

190 x 250 x 250 mm

Judy Darragh

Unique archival digital print

905 x 710 mm

Judy Darragh

Six part collage

460 x 315 mm each

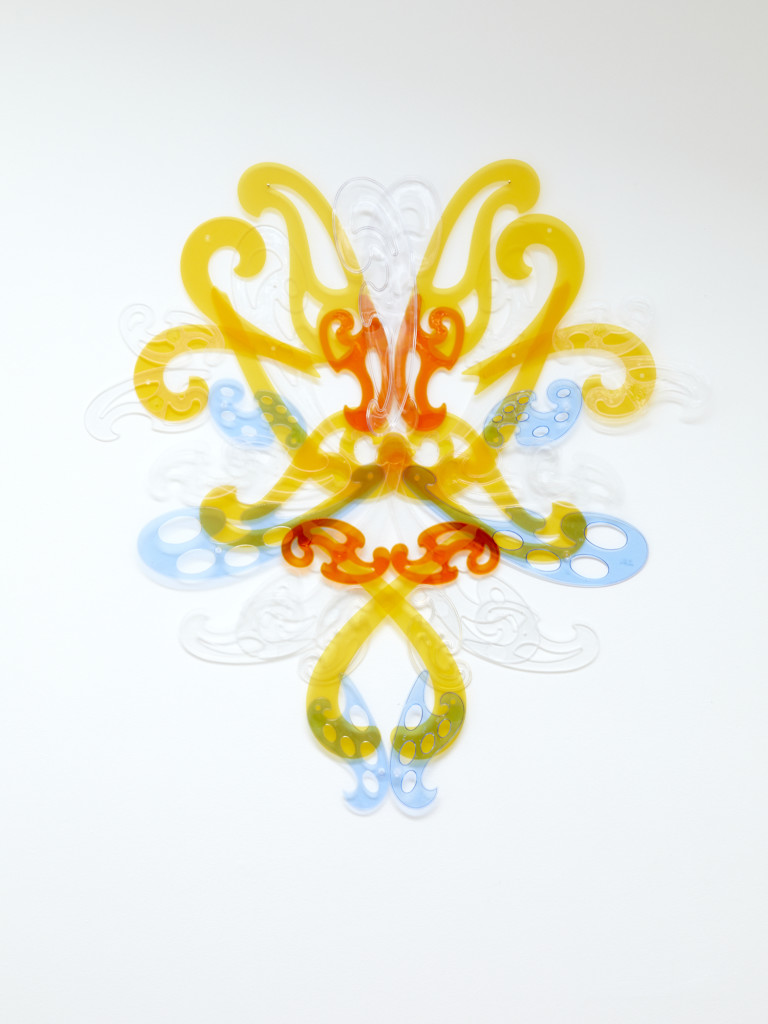

Judy Darragh

Mixed media

1230 x 630 mm

Sean Kerr

Unique cast bronze

150 x 35 mm each

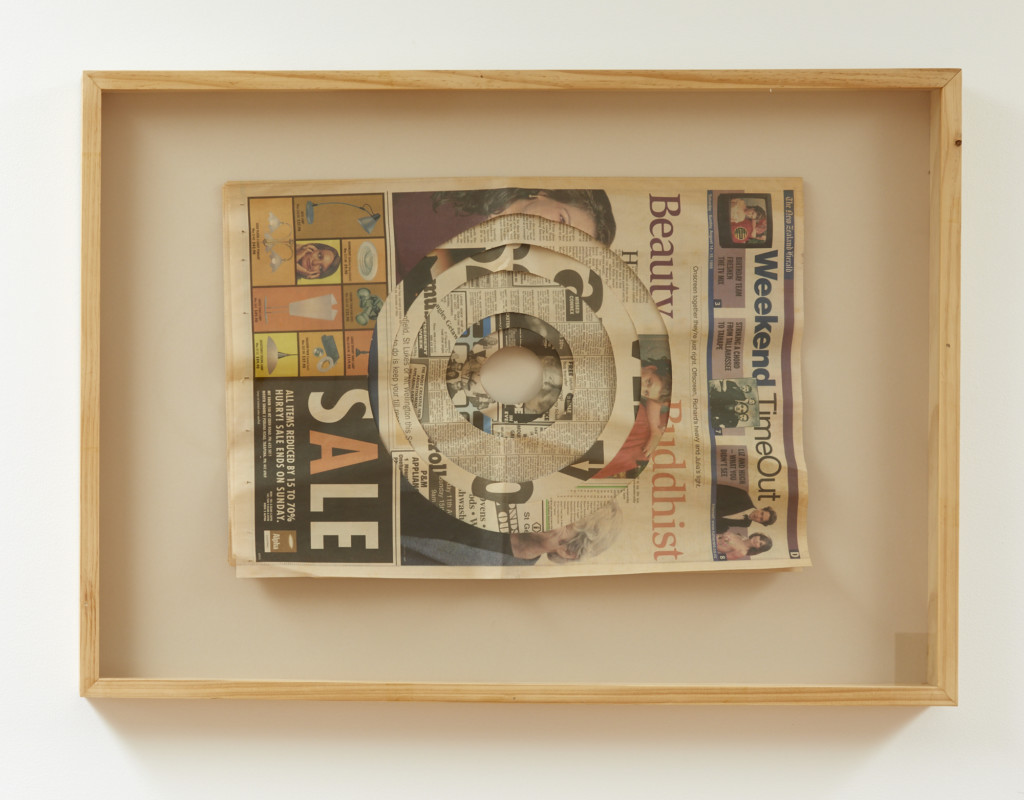

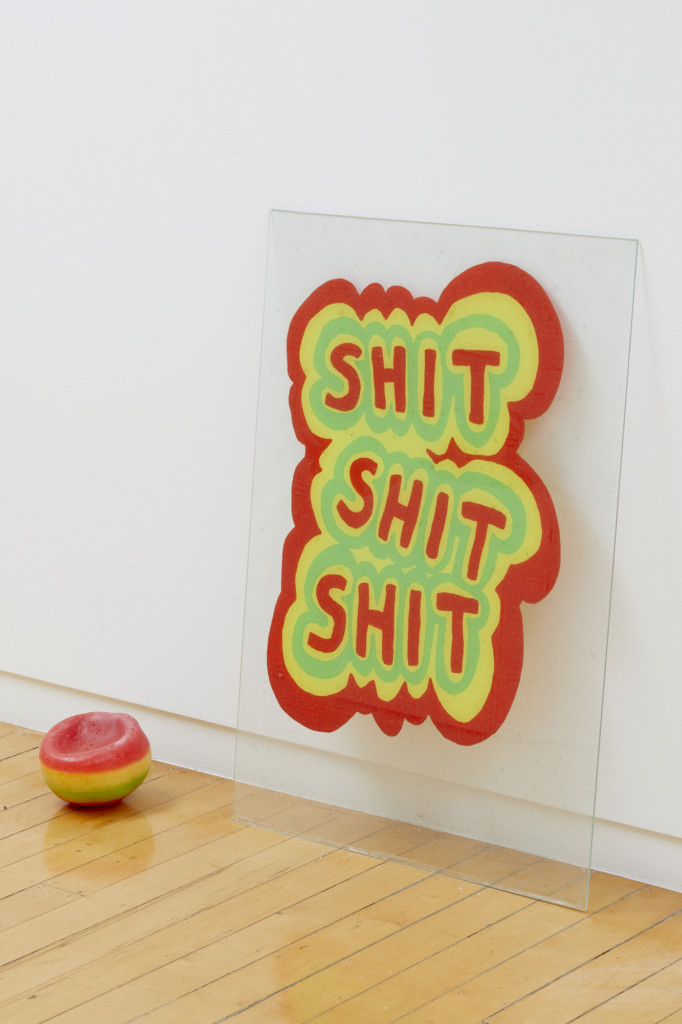

Sean Kerr

Found materials

620 x 870 mm

Sean Kerr

Slip cast ceramic

200 x 290 x 200 mm

Sean Kerr

Cast resin

220 x 130 x100 mm

Unique synchronized HD video

773 x 887 mm

Sean Kerr

Recycled aluminium

150 x 340 x 120 mm

Sean Kerr

Mixed media

860 x 610 mm