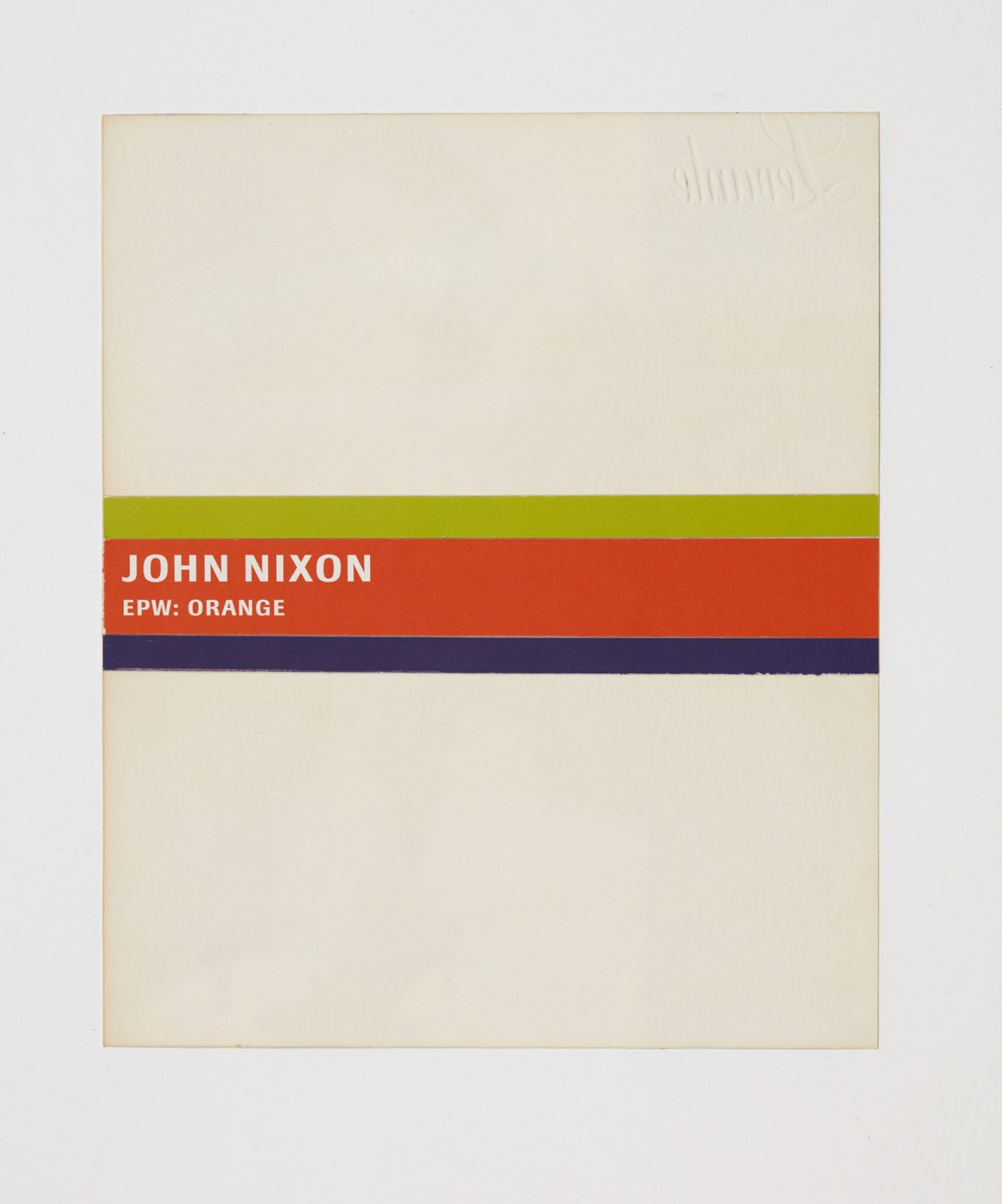

John Nixon

Collages: selected works

28 April - 27 May 2017

Modernism in the Medicine Cabinet.

Collages: Selected Works brings together 110 previously un-exhibited John Nixon collages produced over the last 30 years. Collages has come together in a timely manner alongside John Nixon: Abstraction, a 30 year survey of his paintings drawn from the Chartwell Collection, a separate self-contained presentation within the Auckland Art Gallery’s broader exhibition Colour is An Abstraction.

Colour is An Abstraction reflects on international artists’ exploration of colour in the late Twentieth and Twenty First Centuries, contemplating its numerous social and psychological roles. Nixon’s contribution of paintings were acquired by Chartwell Collection founder Rob Gardiner, a long-term supporter of his work.

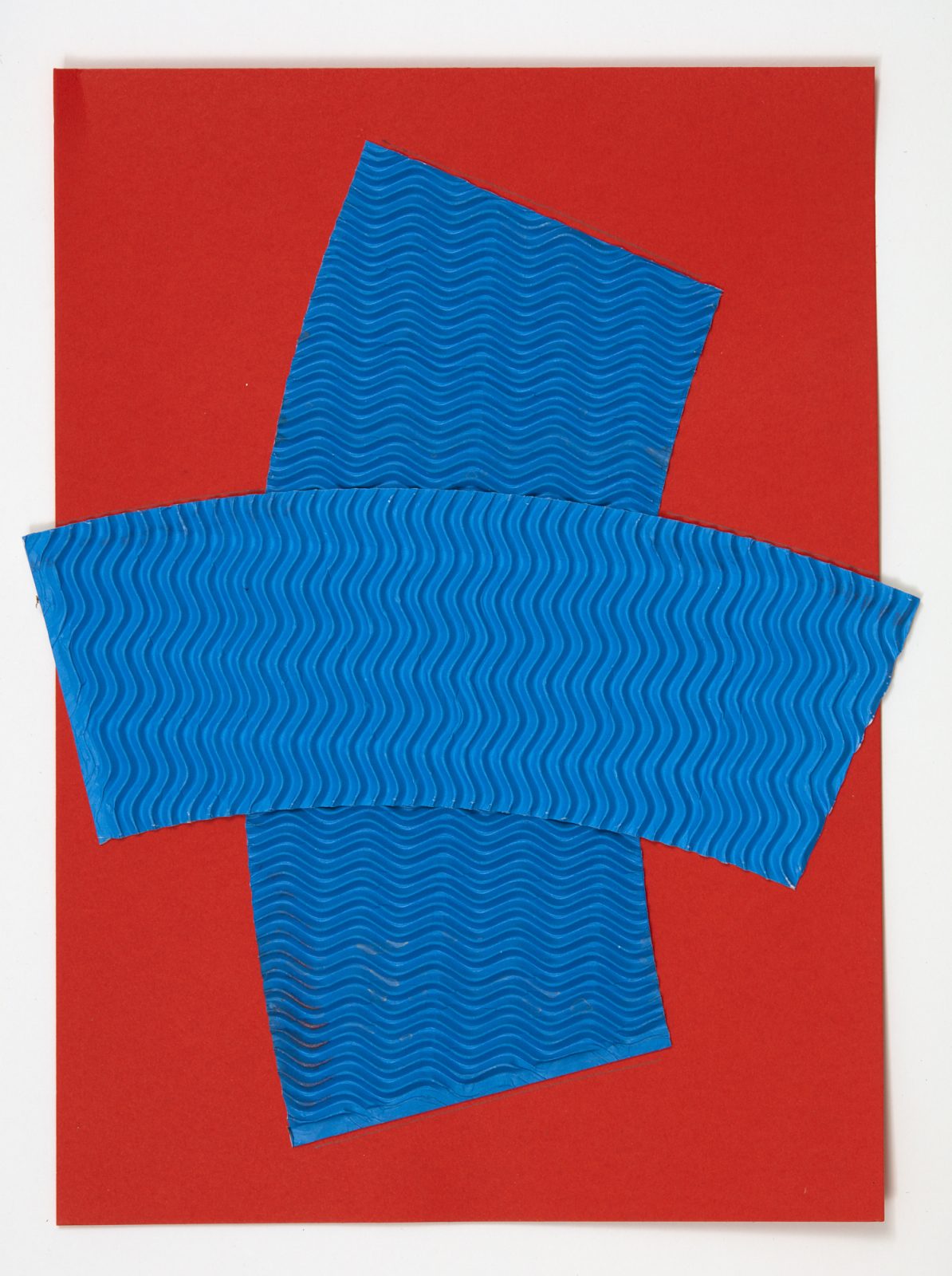

Collages at Two Rooms proposes a parallel exhibition, one which establishes a dialogue with and counterpoint to Nixon’s Auckland Art Gallery painting survey. This exhibition brings together a large collection of collages made over an extended period, which he asserts, “present an even more open and experimental vocabulary than the paintings.” Nixon’s comment prompts a reconsideration of the roles collage plays in his practice, particularly in relation to painting. Further, it encourages reflection on the unique medium of collage and its capacity to remain open and experimental.

The eclectic histories of collage span the movements of Constructivism, Cubism, Dada, Surrealism, Pop Art, Fluxus and Conceptual Art (to name a few). They further scatter in to an array of contemporary appropriations and remixes in diverse media from the zine to the GIF. What is at stake – both in the historical roots of collage and our current fragmented, pluralistic aesthetic situation – is the potential, and the need, to experiment.

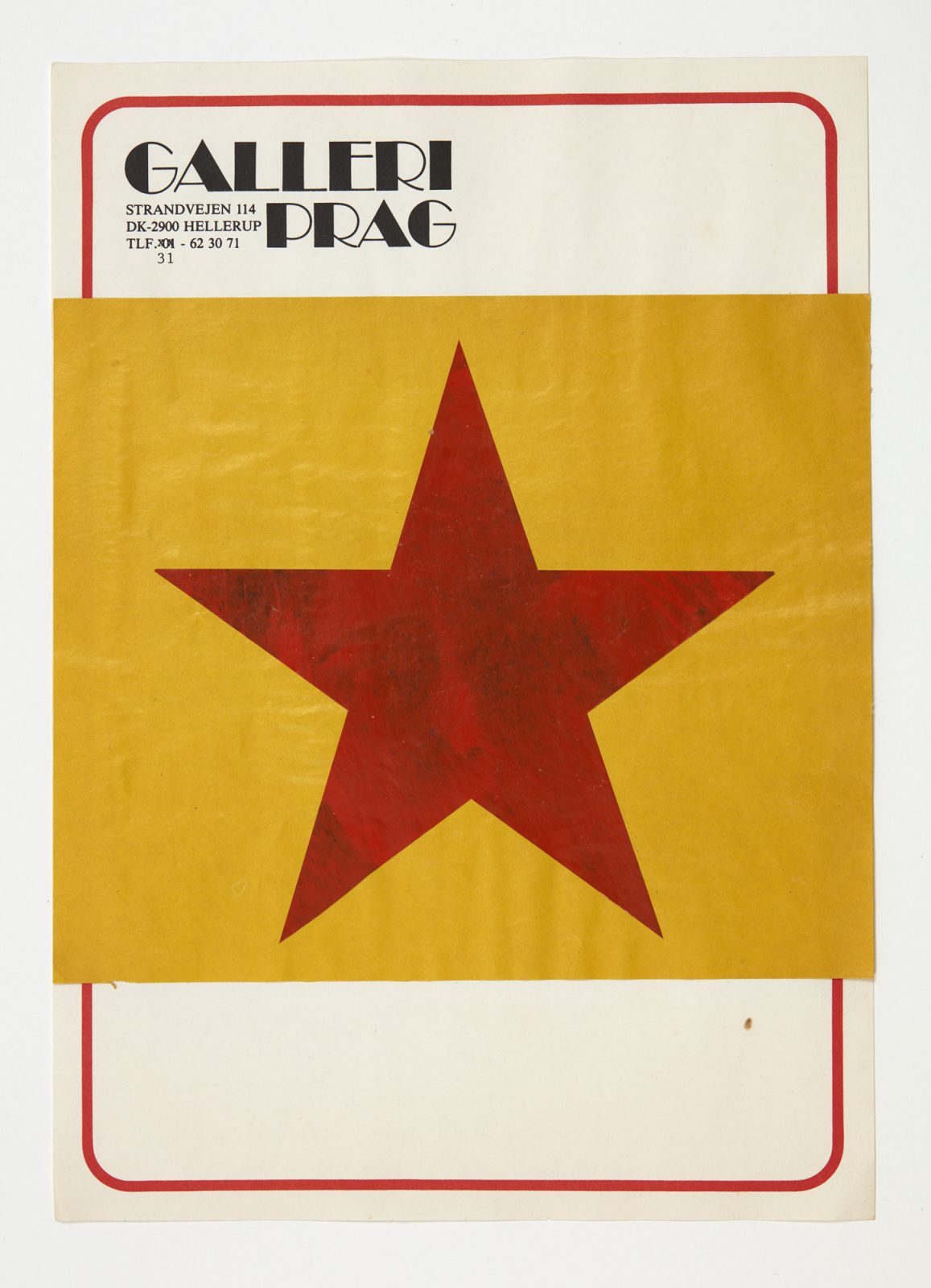

As a medium and a tradition, collage has no explicit politics. Its emergence in the early Twentieth Century represented a radical departure from established art forms, and a reappraisal of the prevailing ideological, political, economic and social contexts in which they circulated. From formalist innovations to propaganda, collage has since been aesthetically deployed by agents across the political spectrum for well over 100 years and counting.

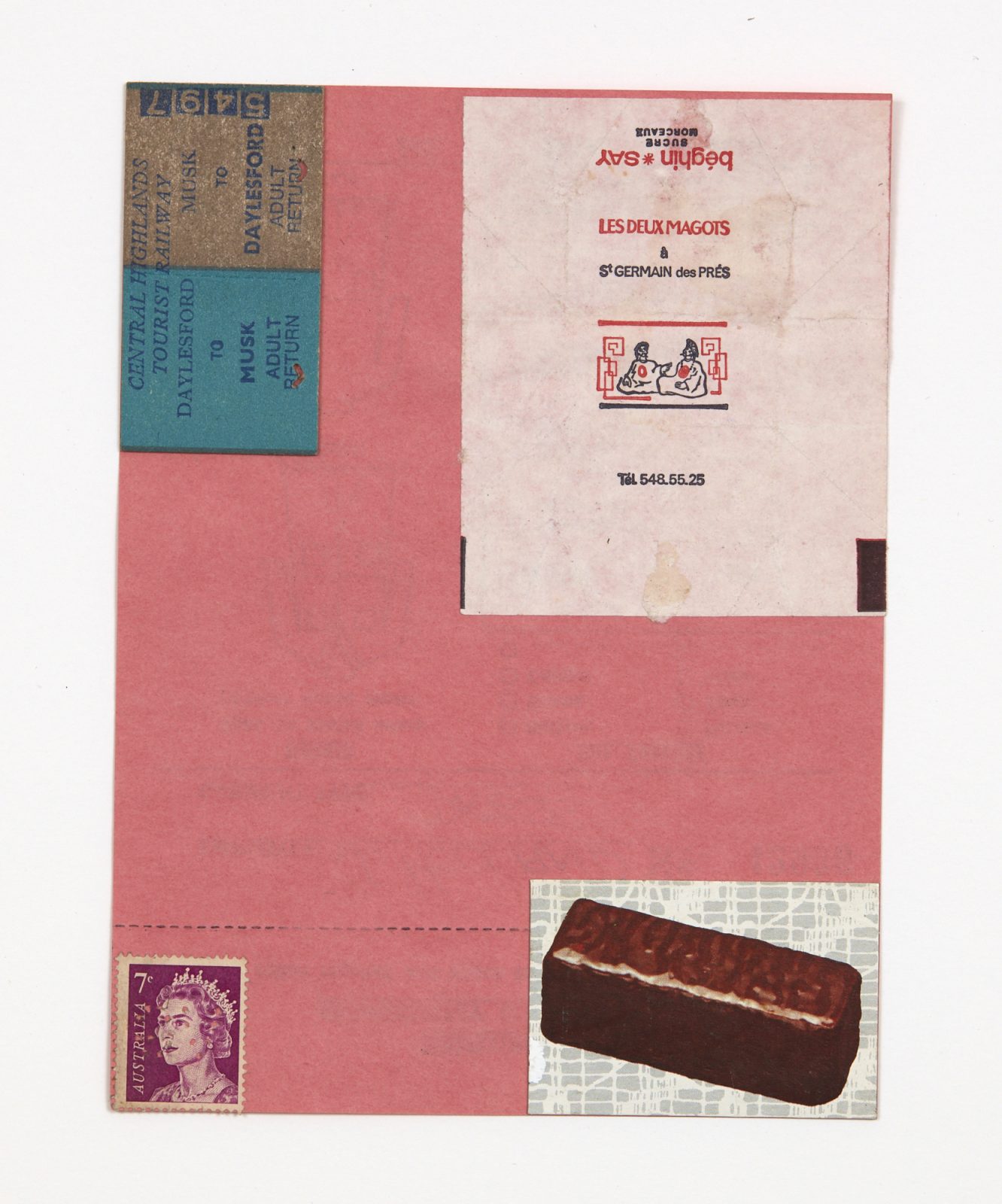

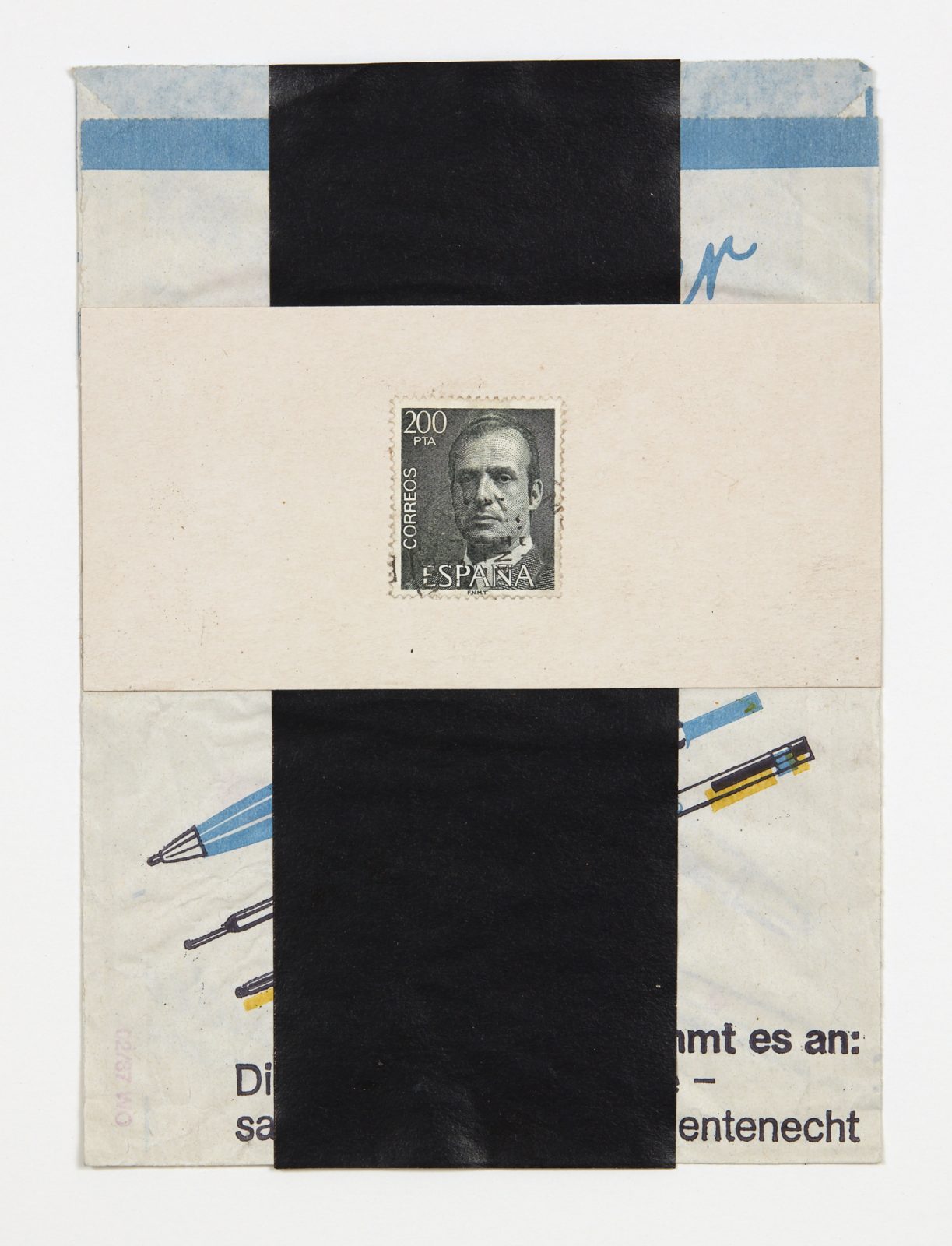

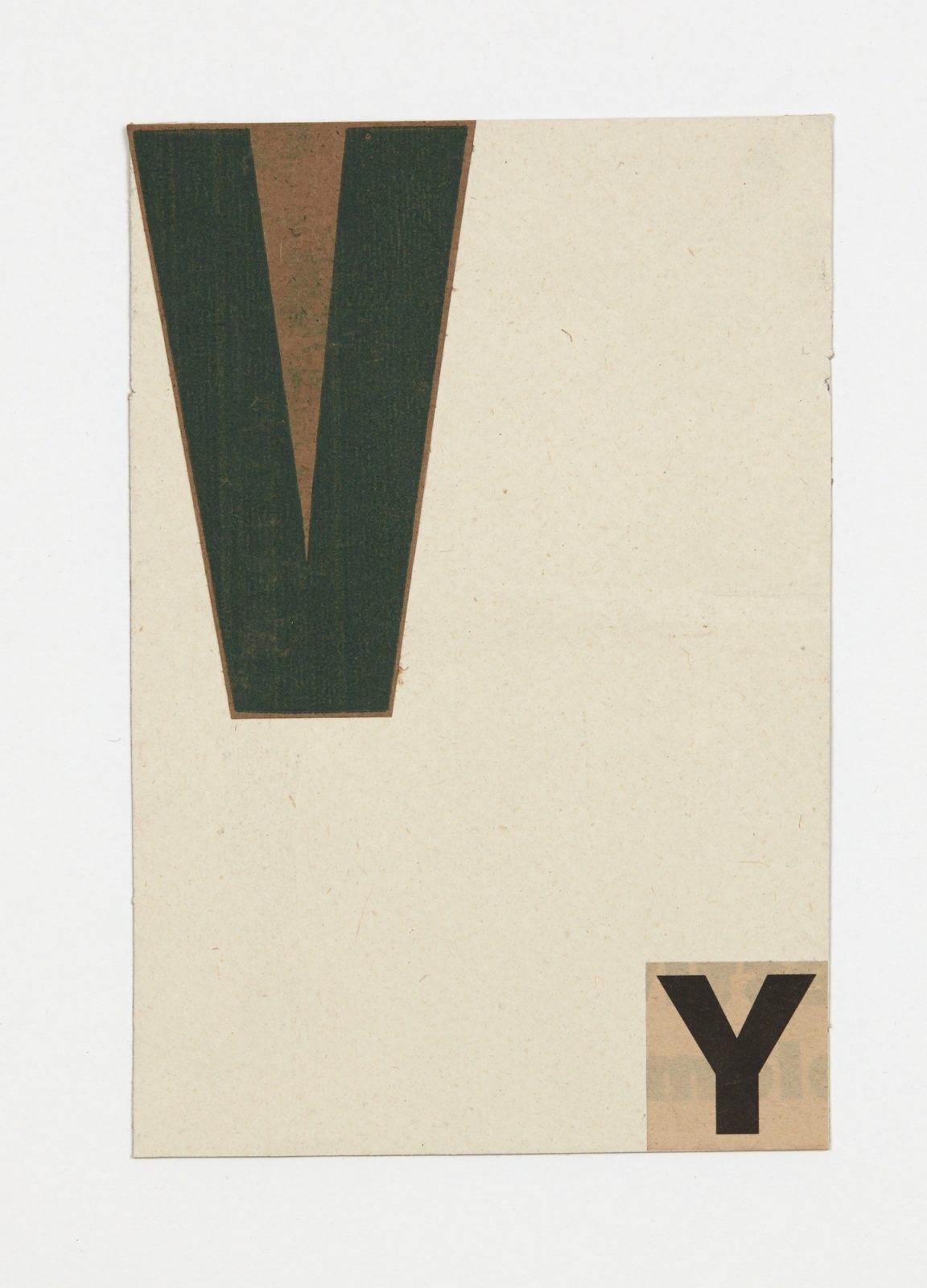

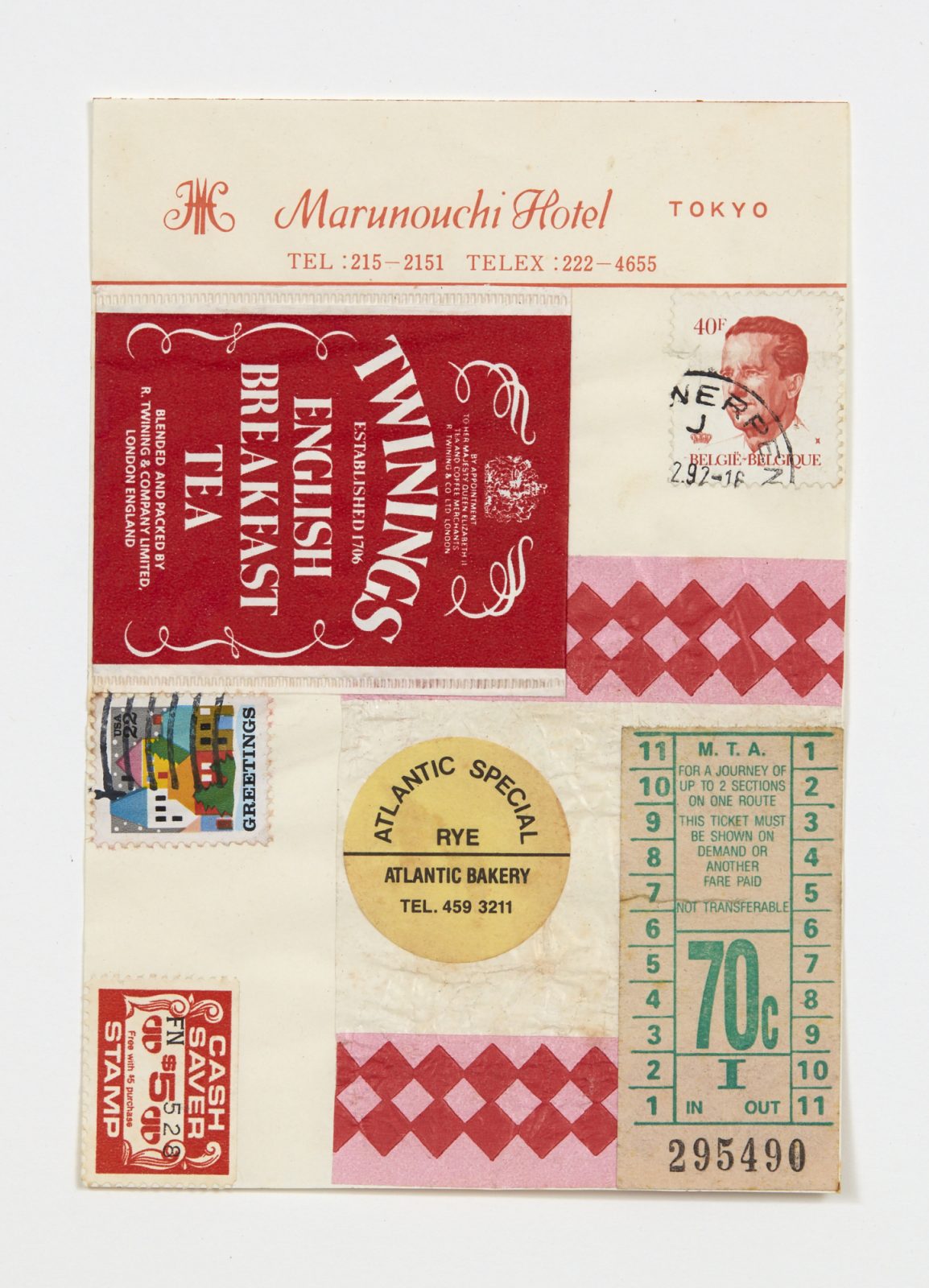

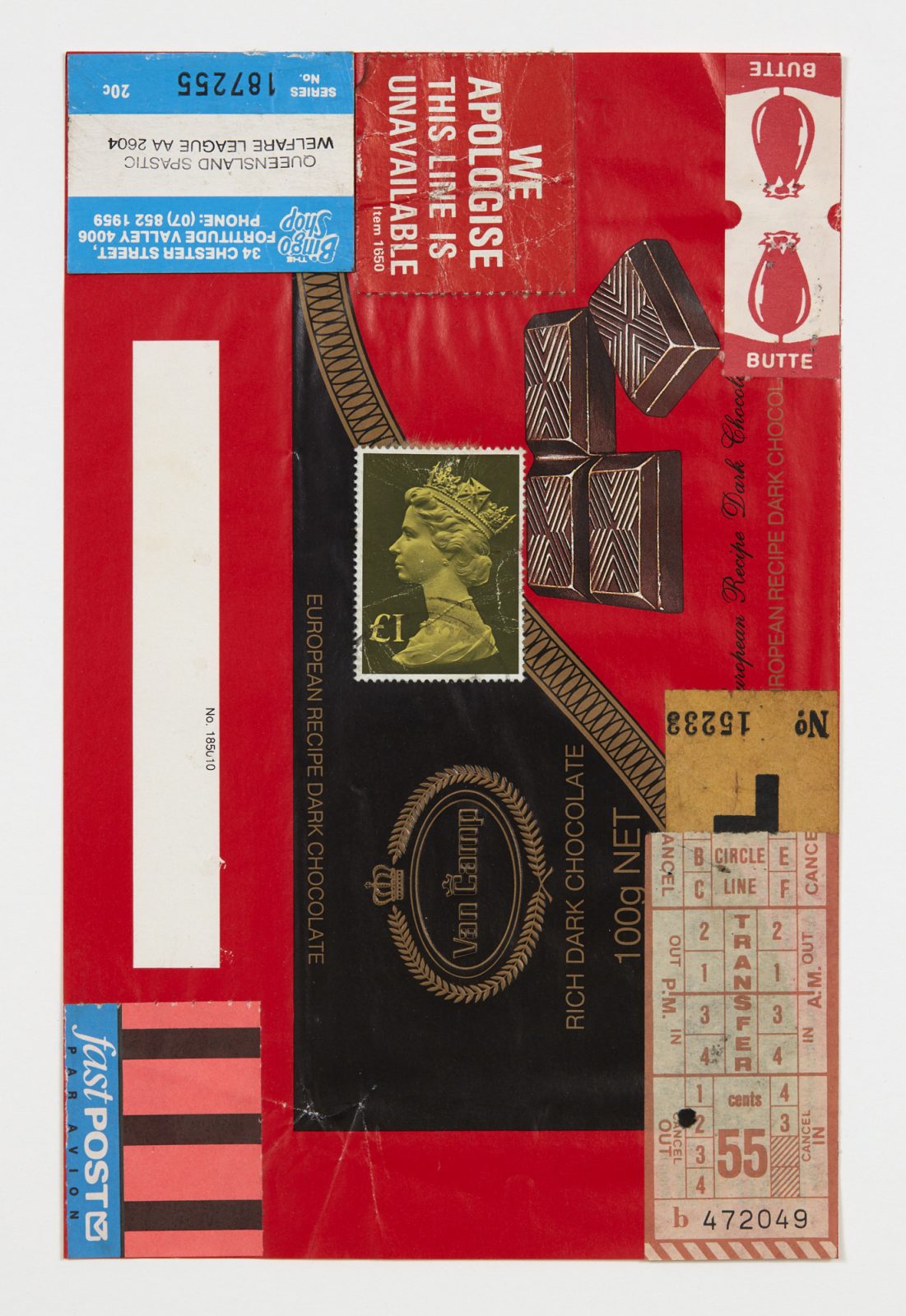

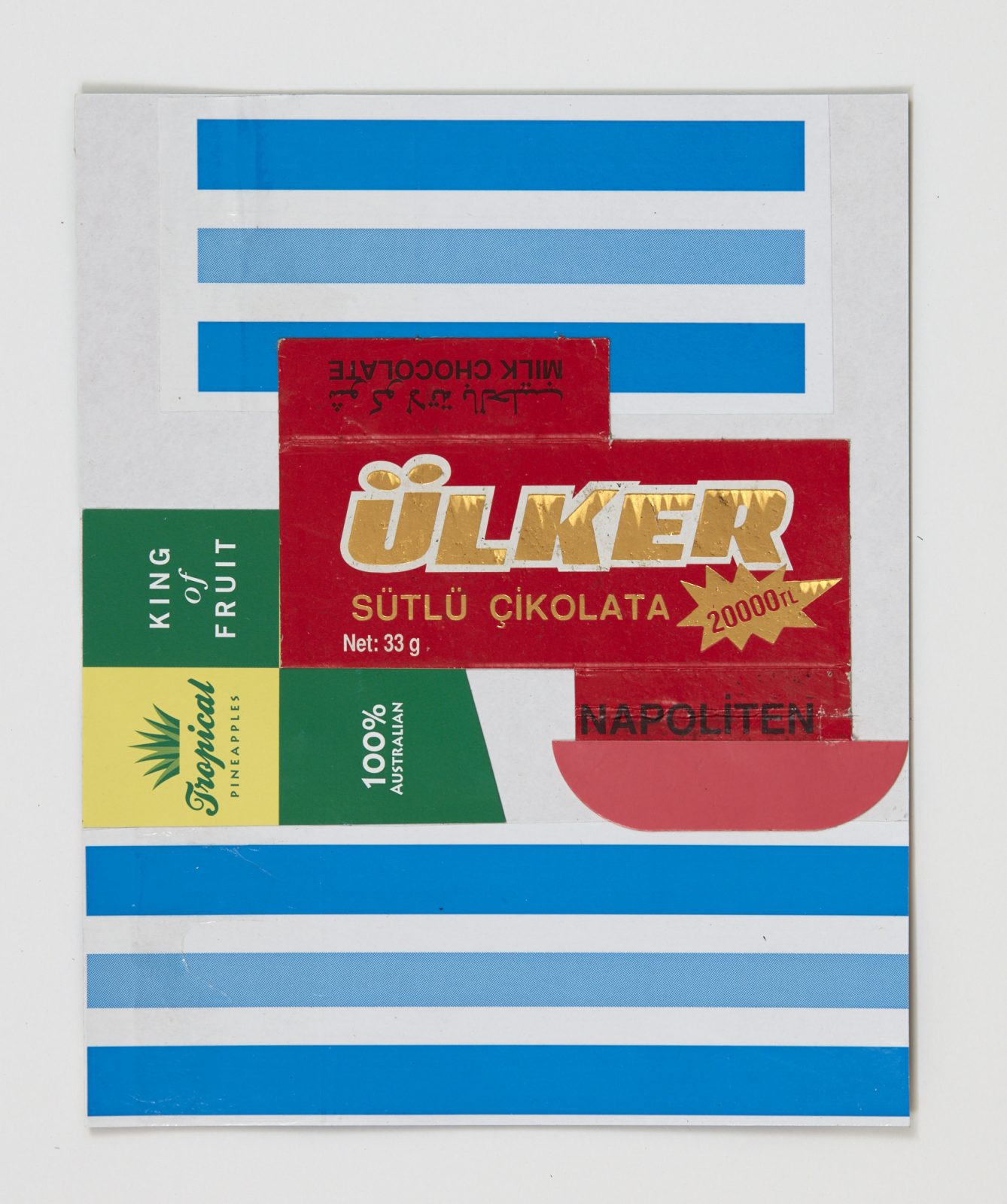

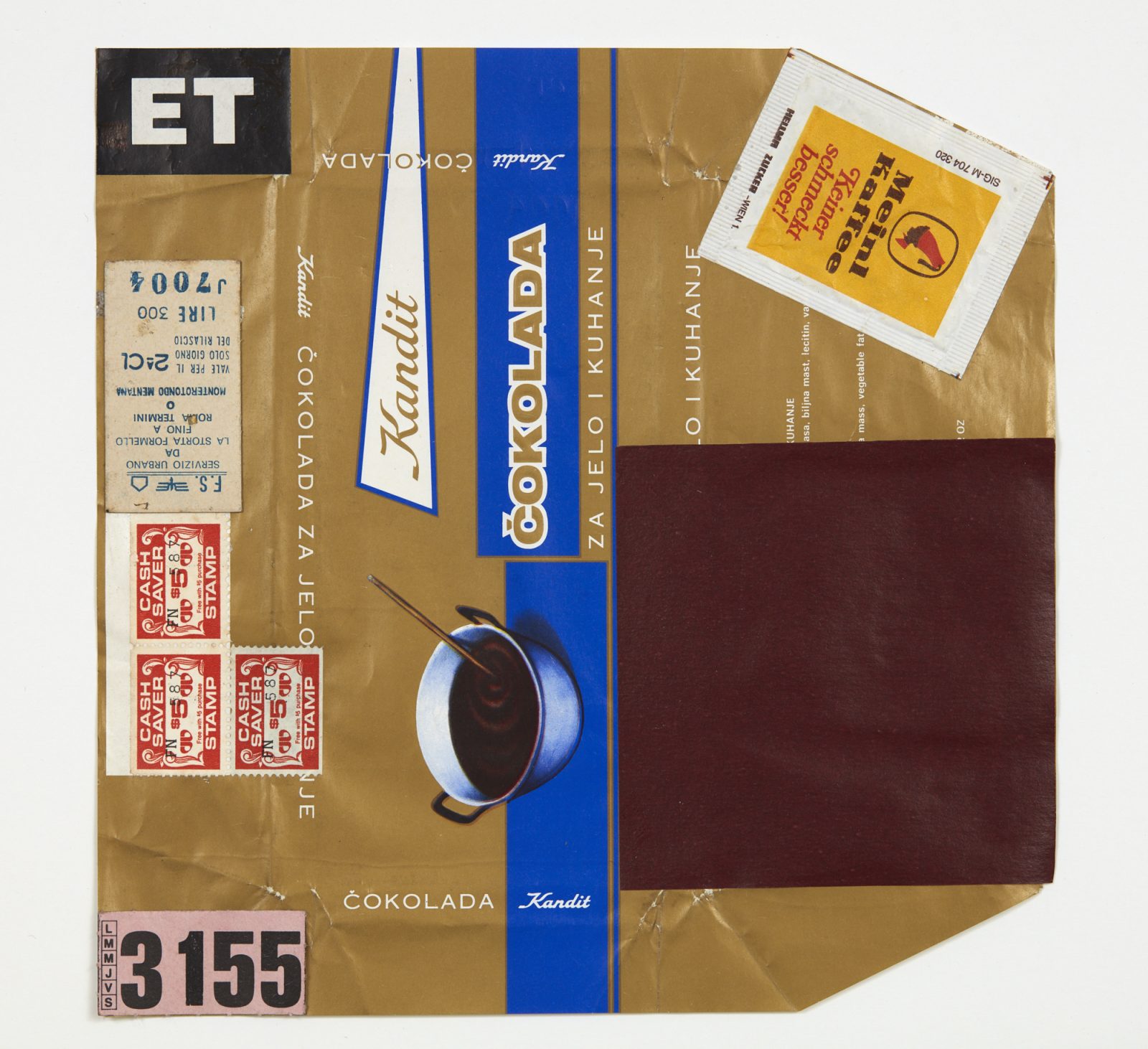

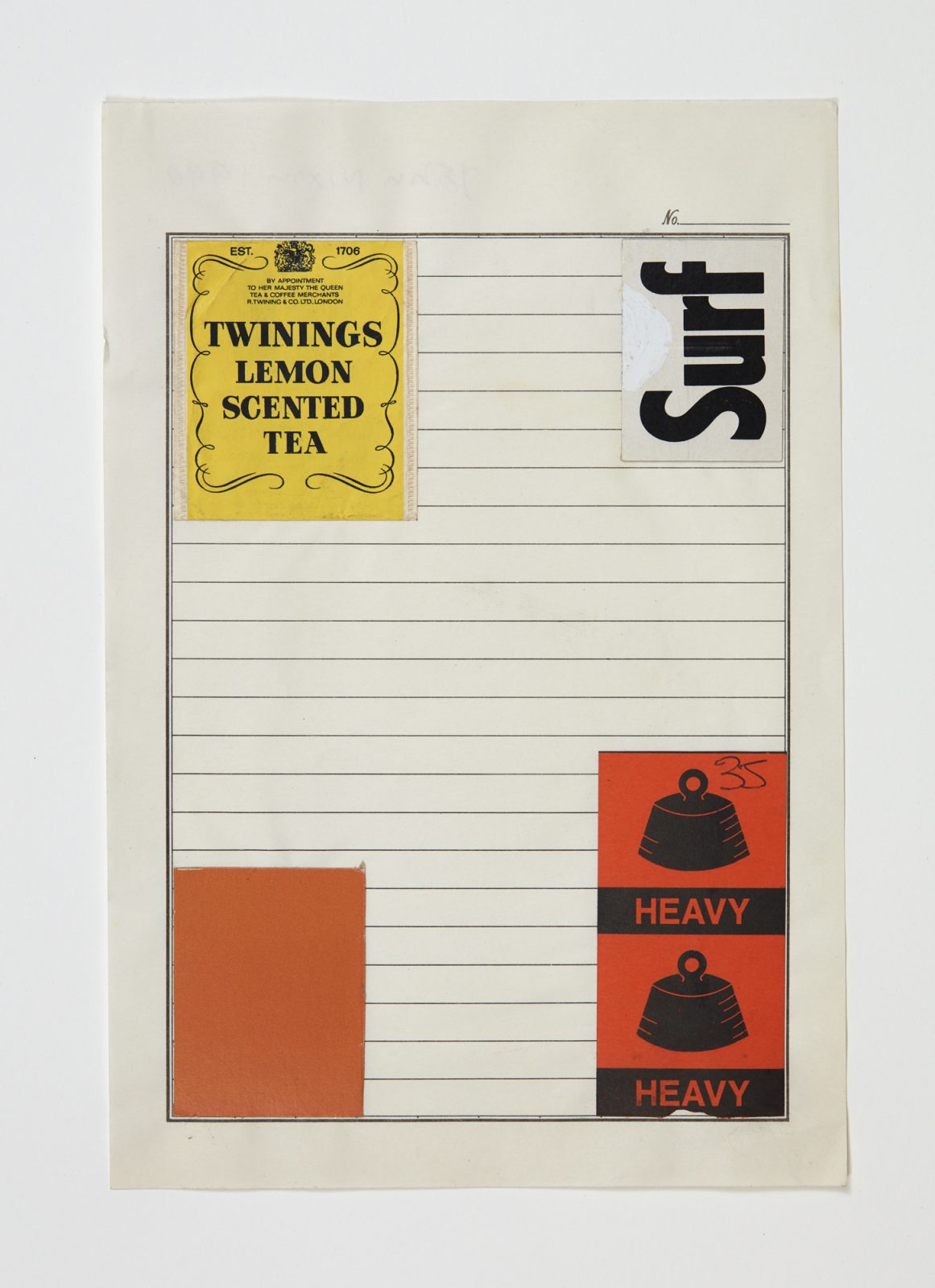

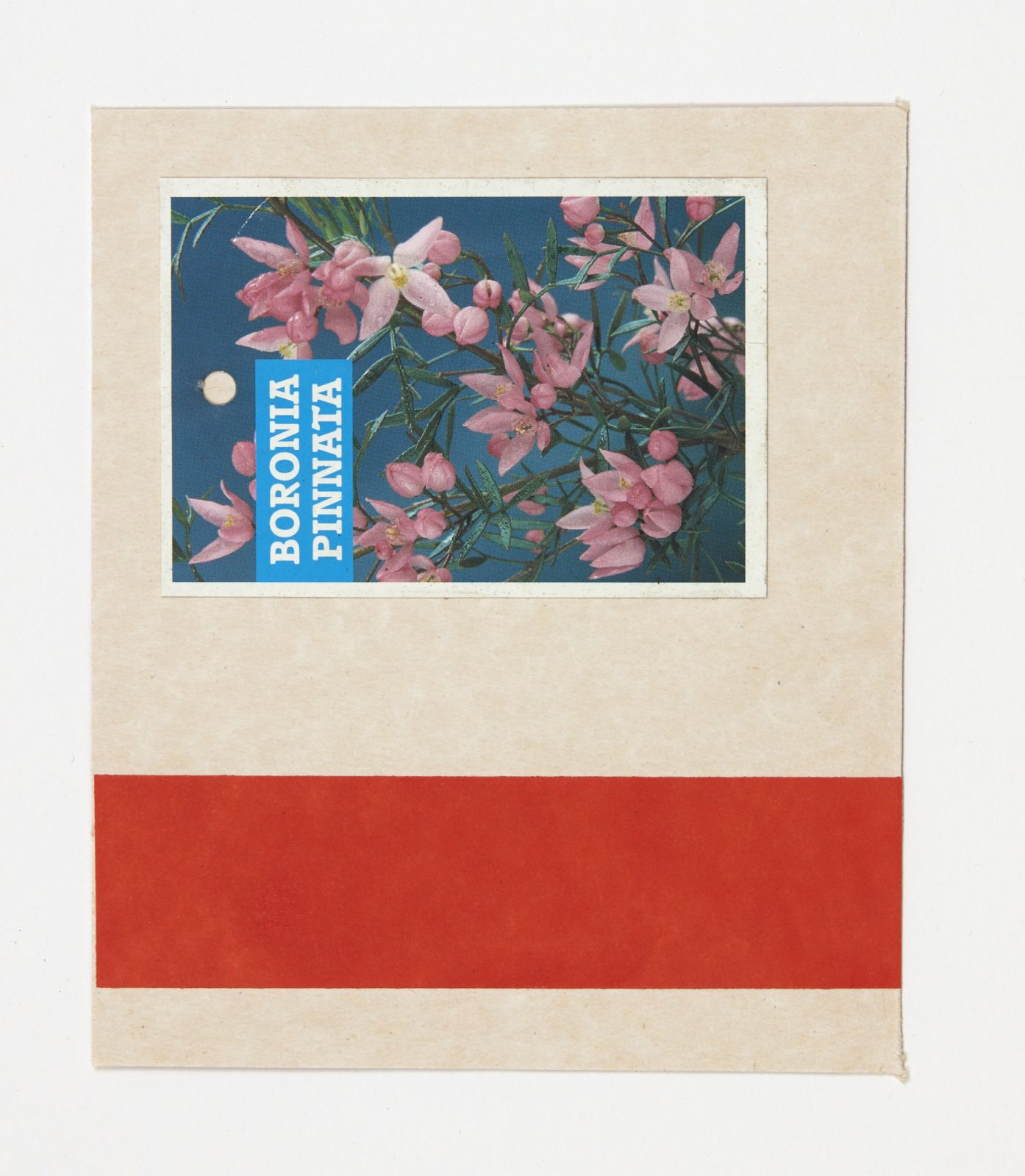

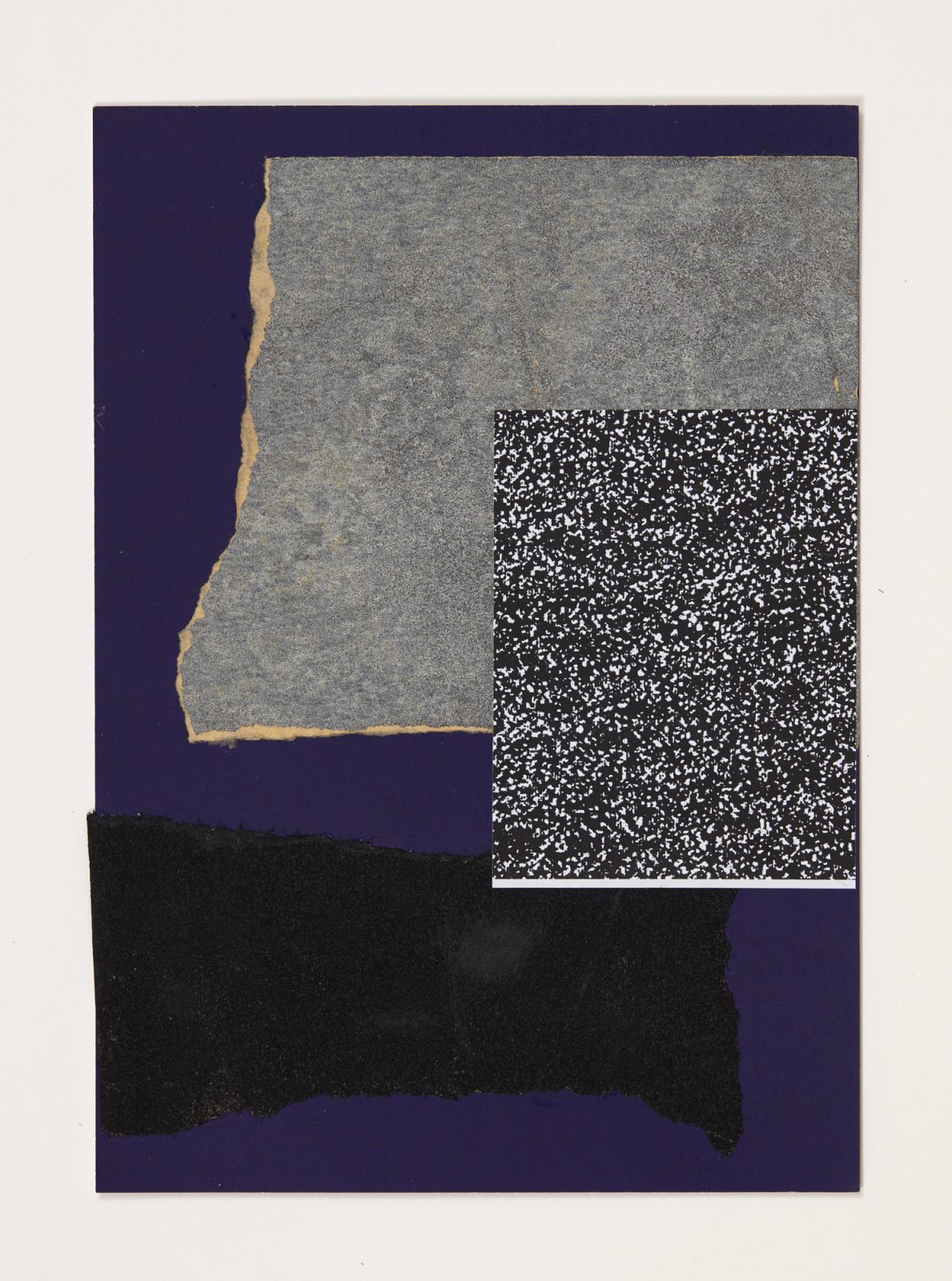

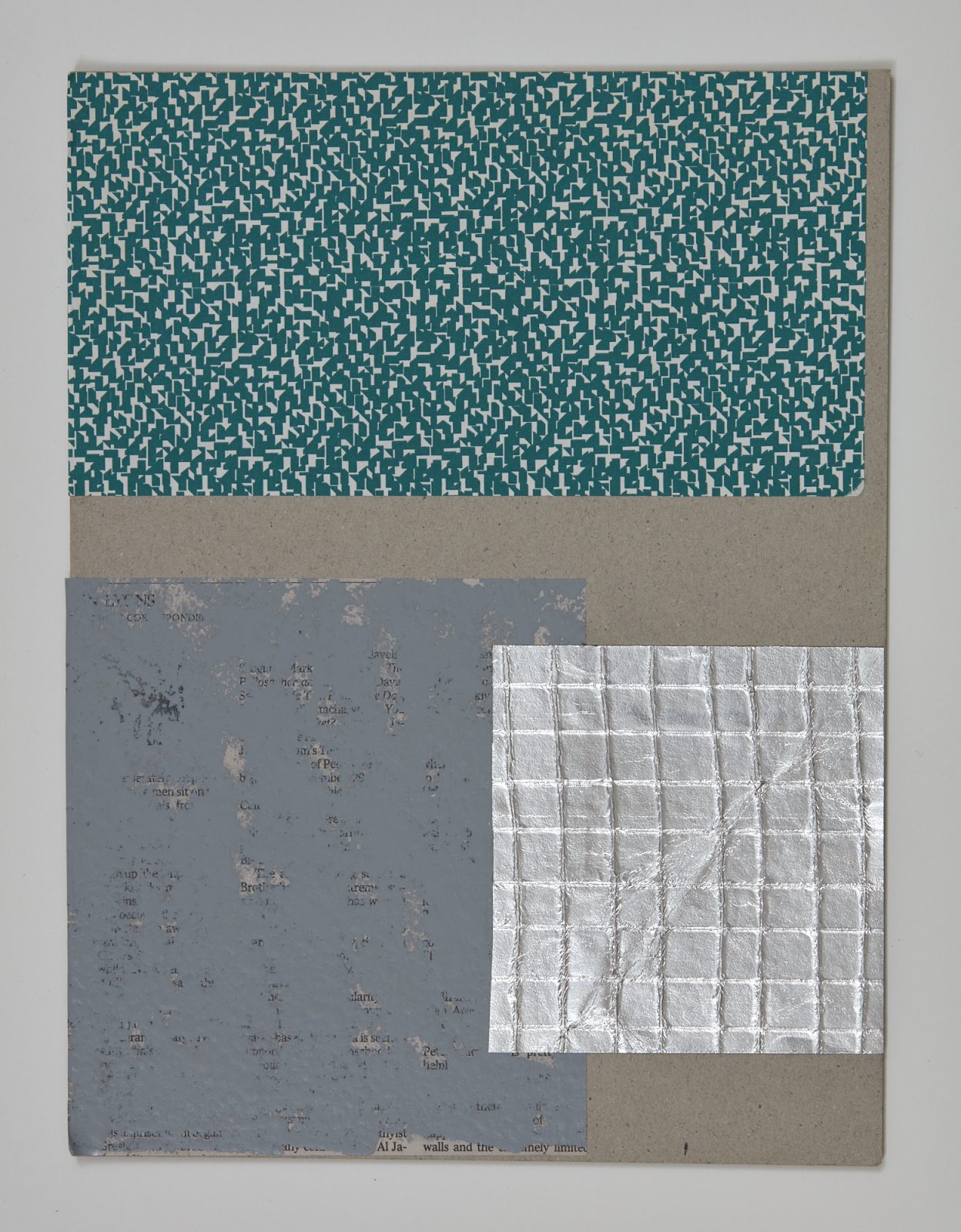

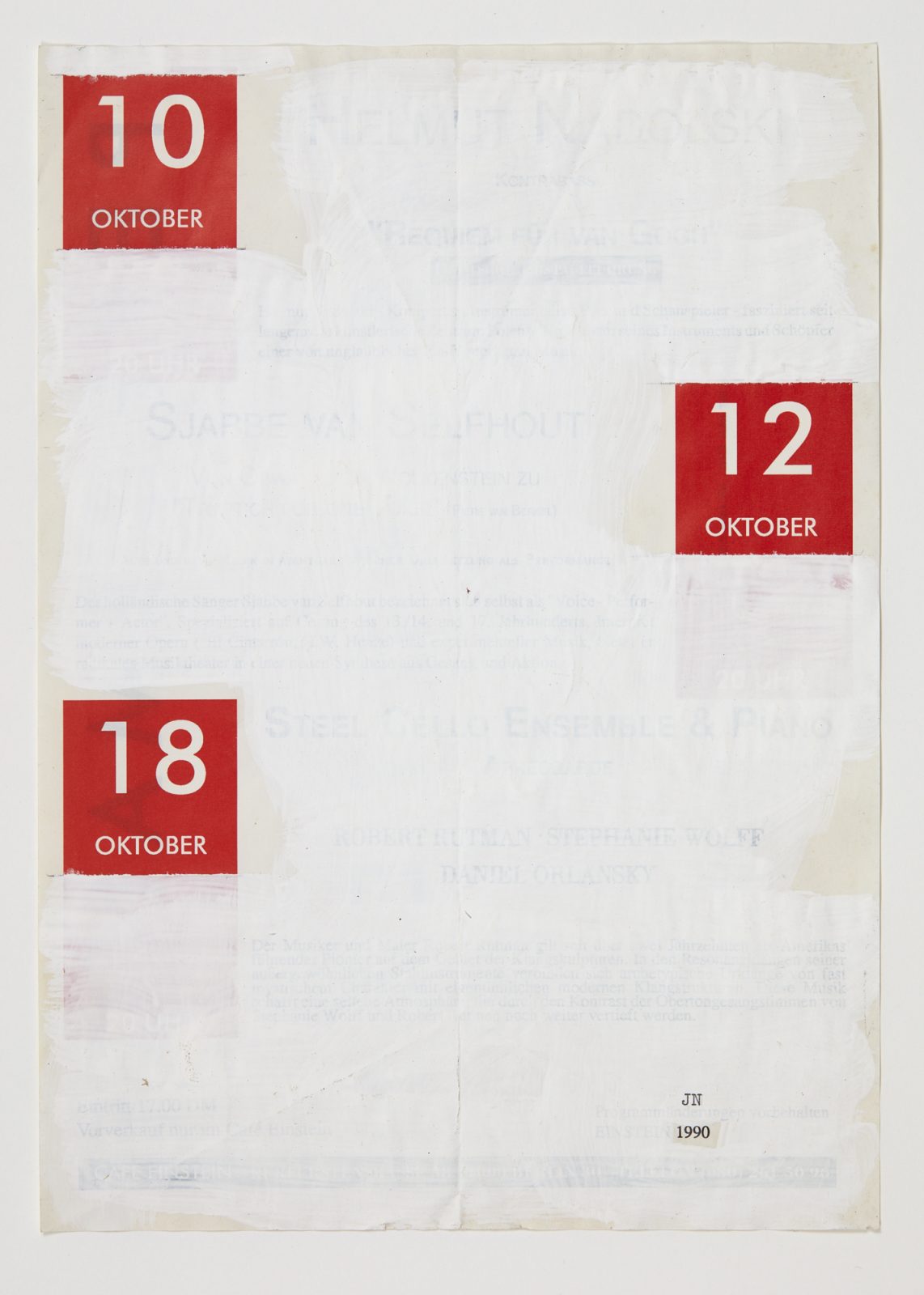

Often playfully critical and subversive, collage transforms everyday materials by juxtaposing disparate images and forms in a new pictorial space where alternate meanings may unfold. Yet these materials also bring part of their original context with them, and at once appear as themselves and something else entirely. Here disparate elements in chance meetings find an unforeseen accord beyond expectation and rationality. The possibilities appear endless.

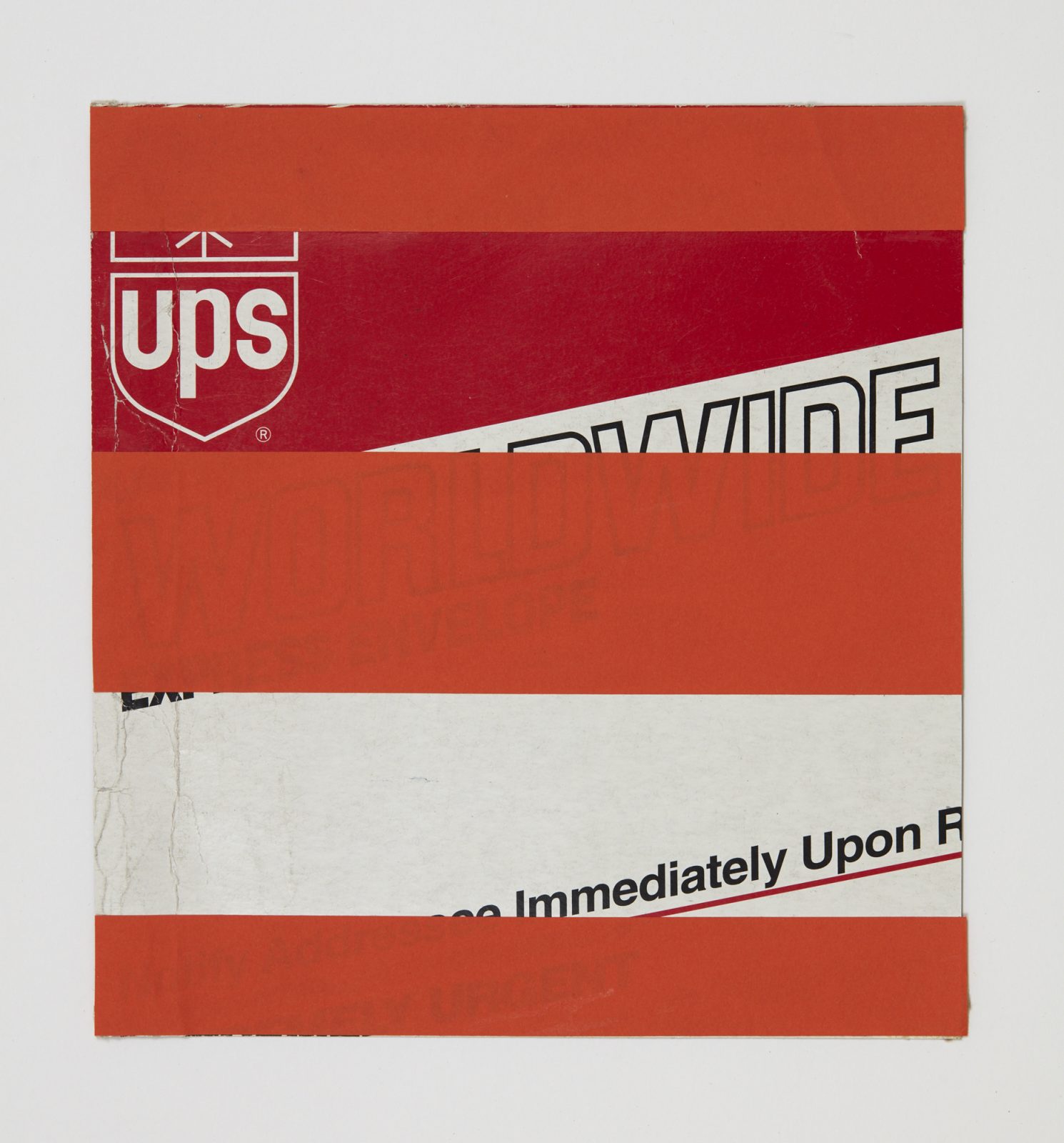

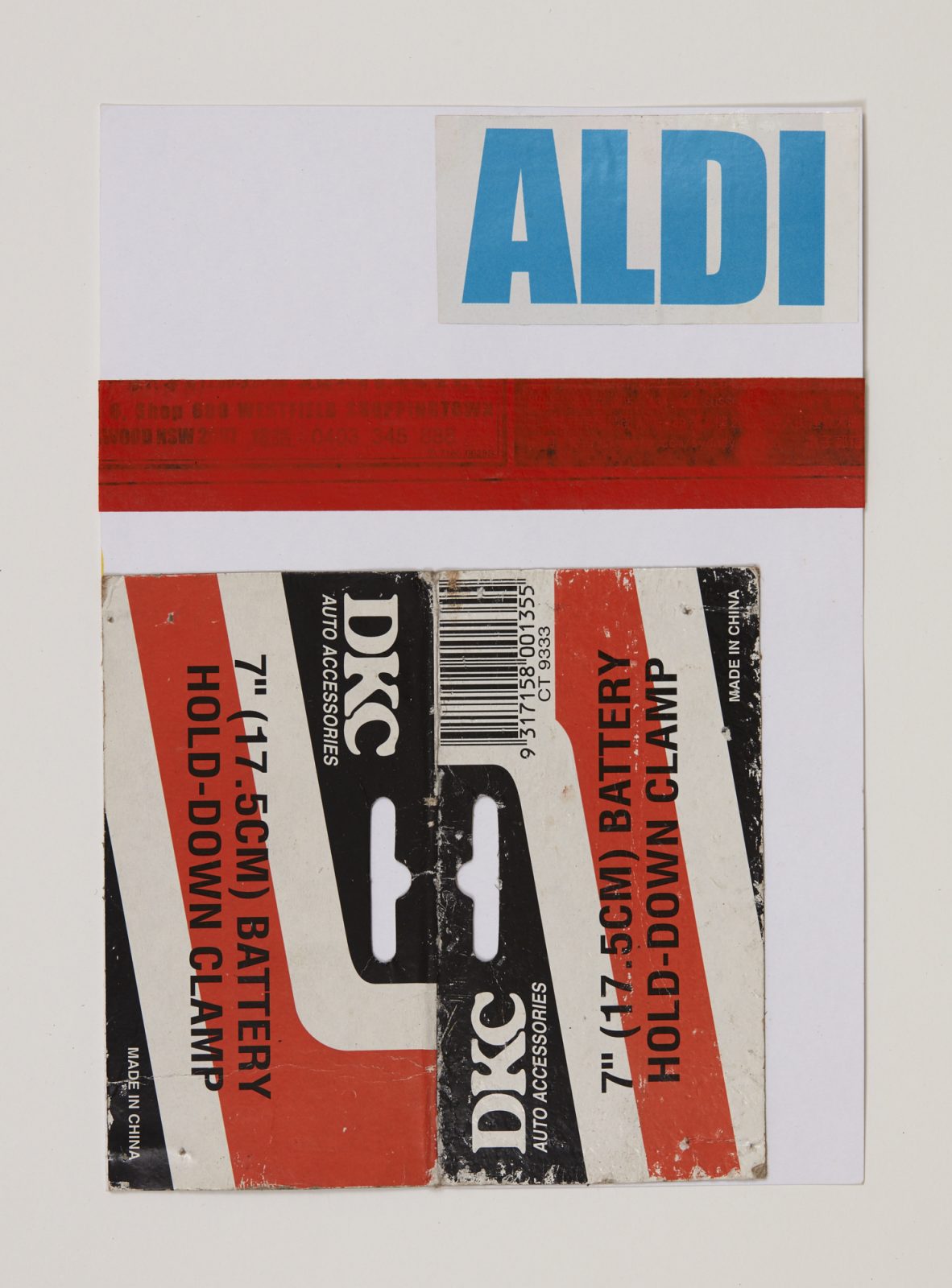

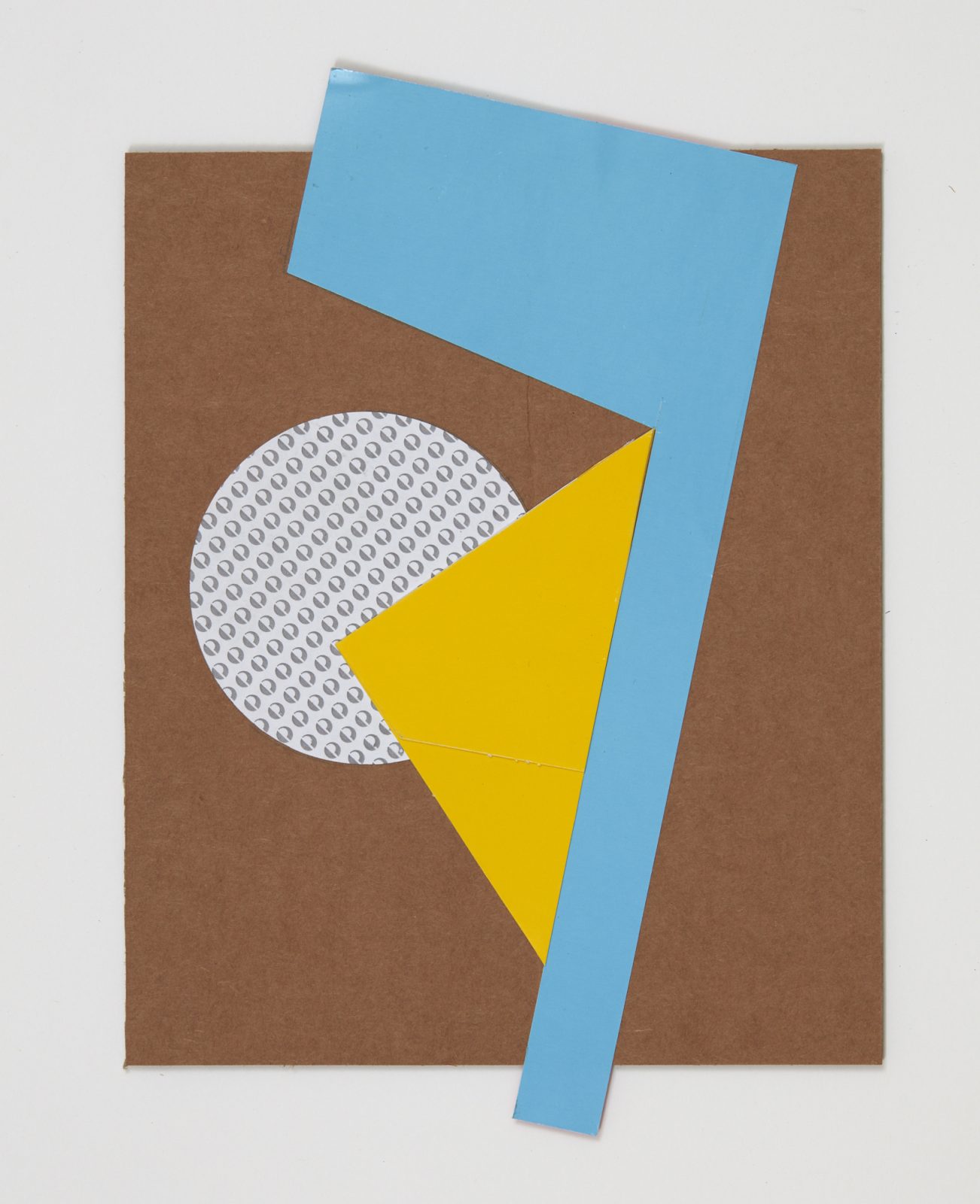

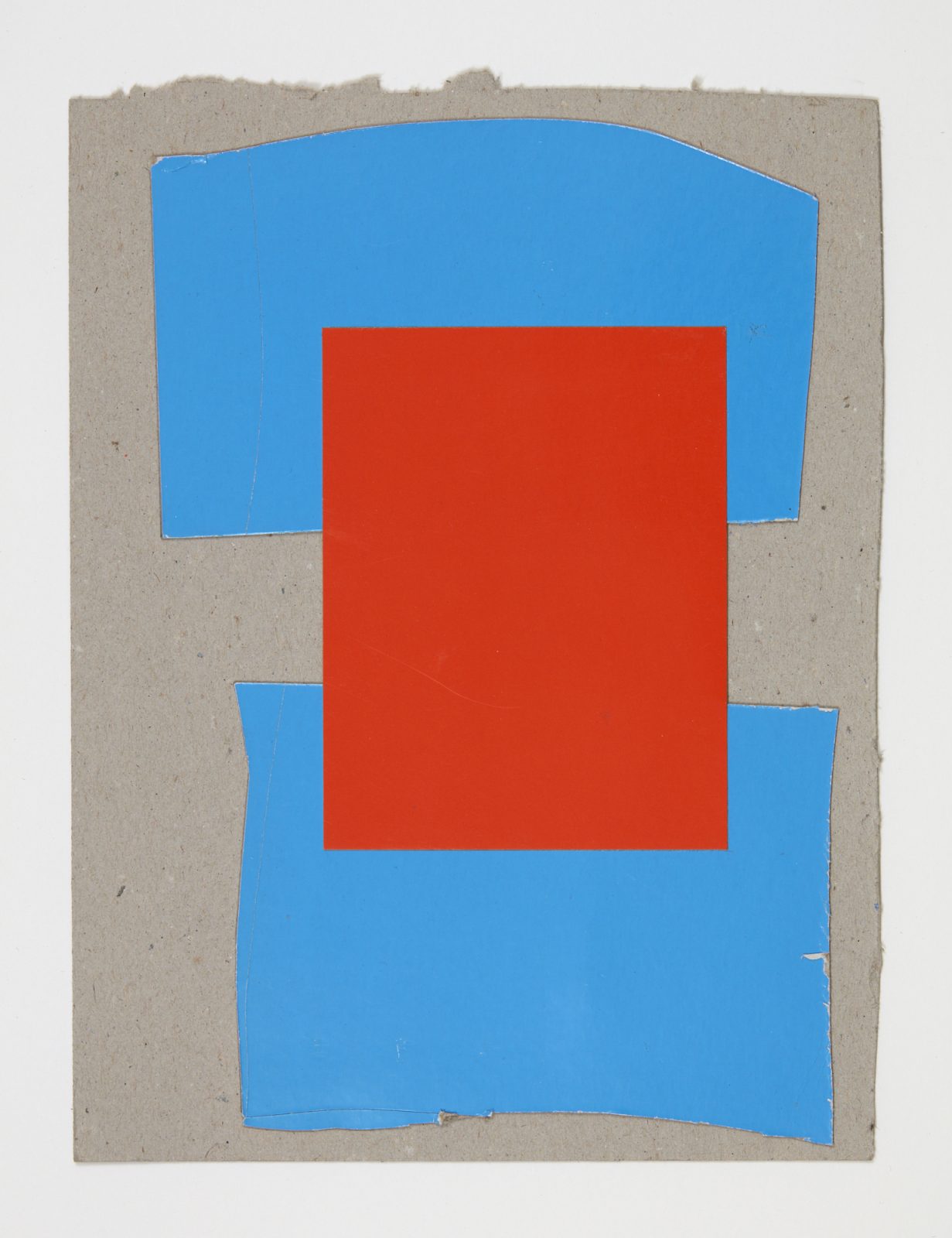

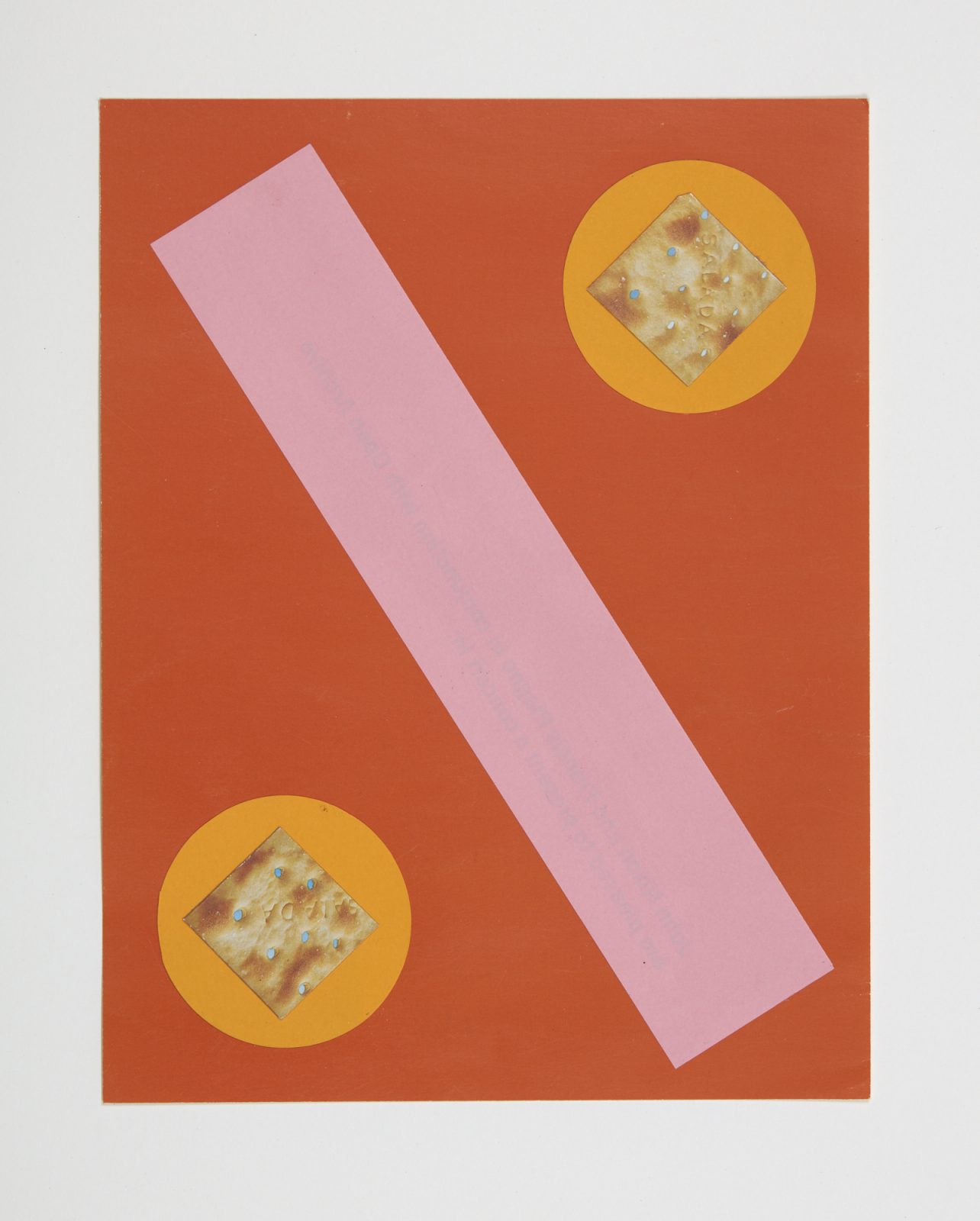

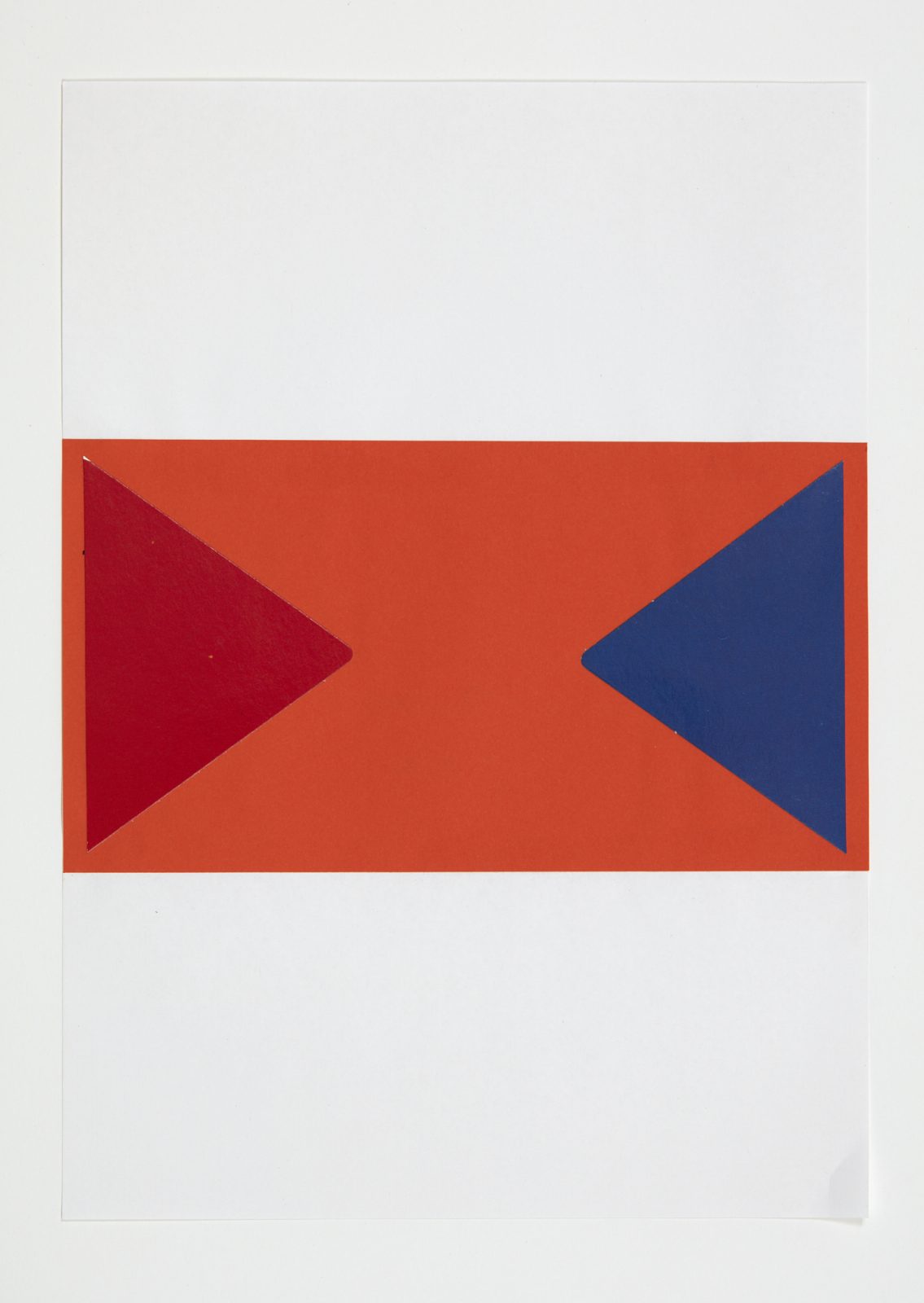

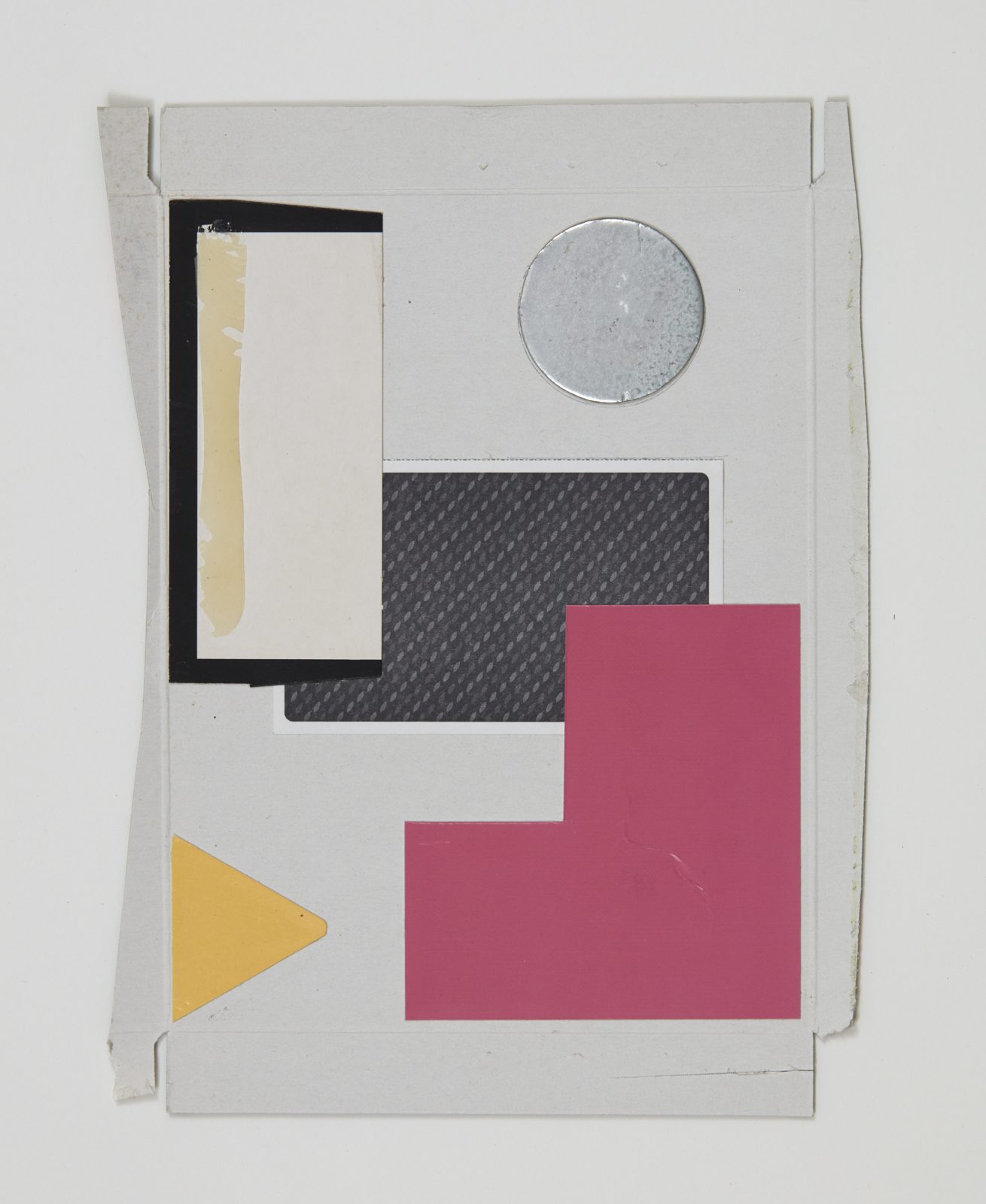

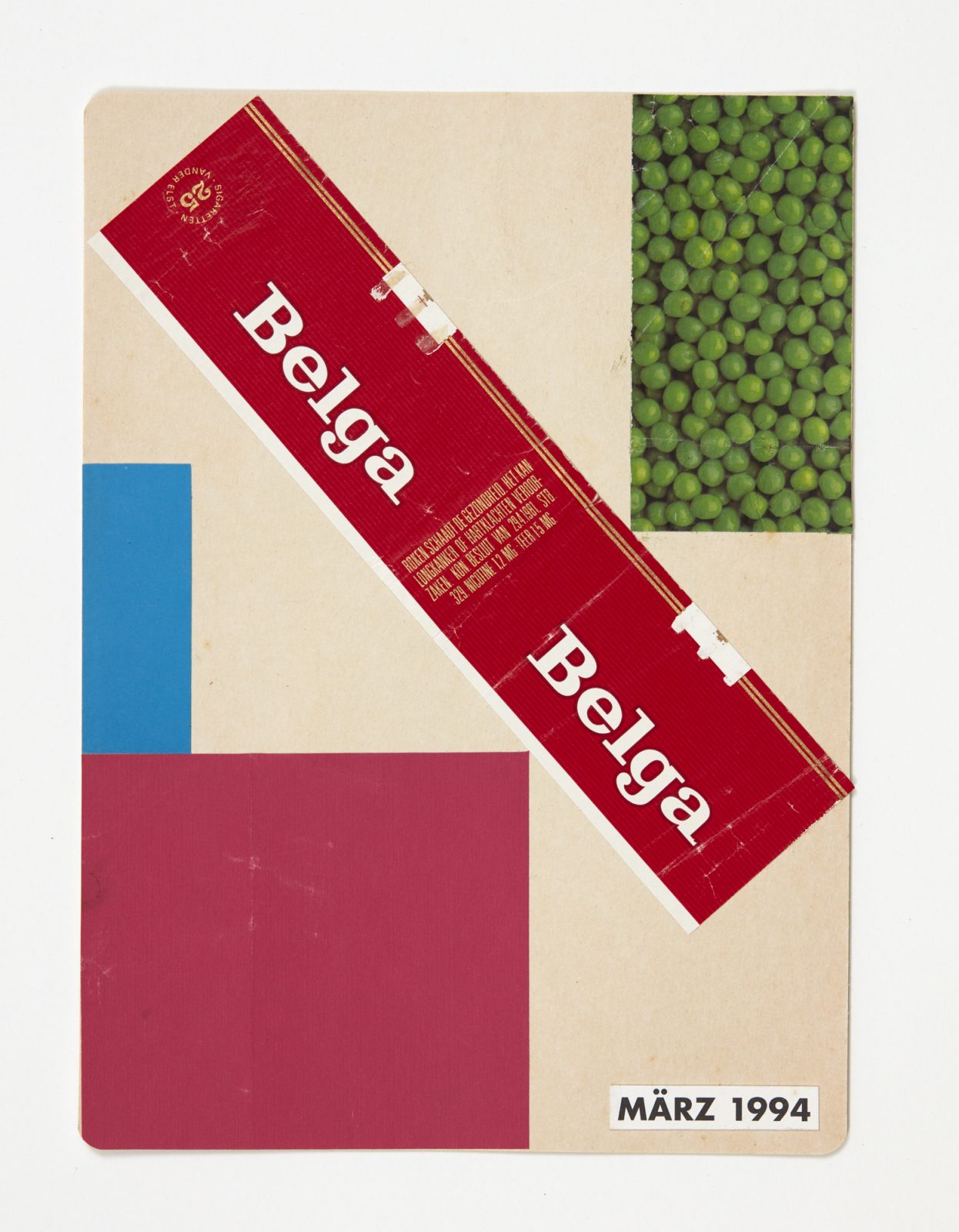

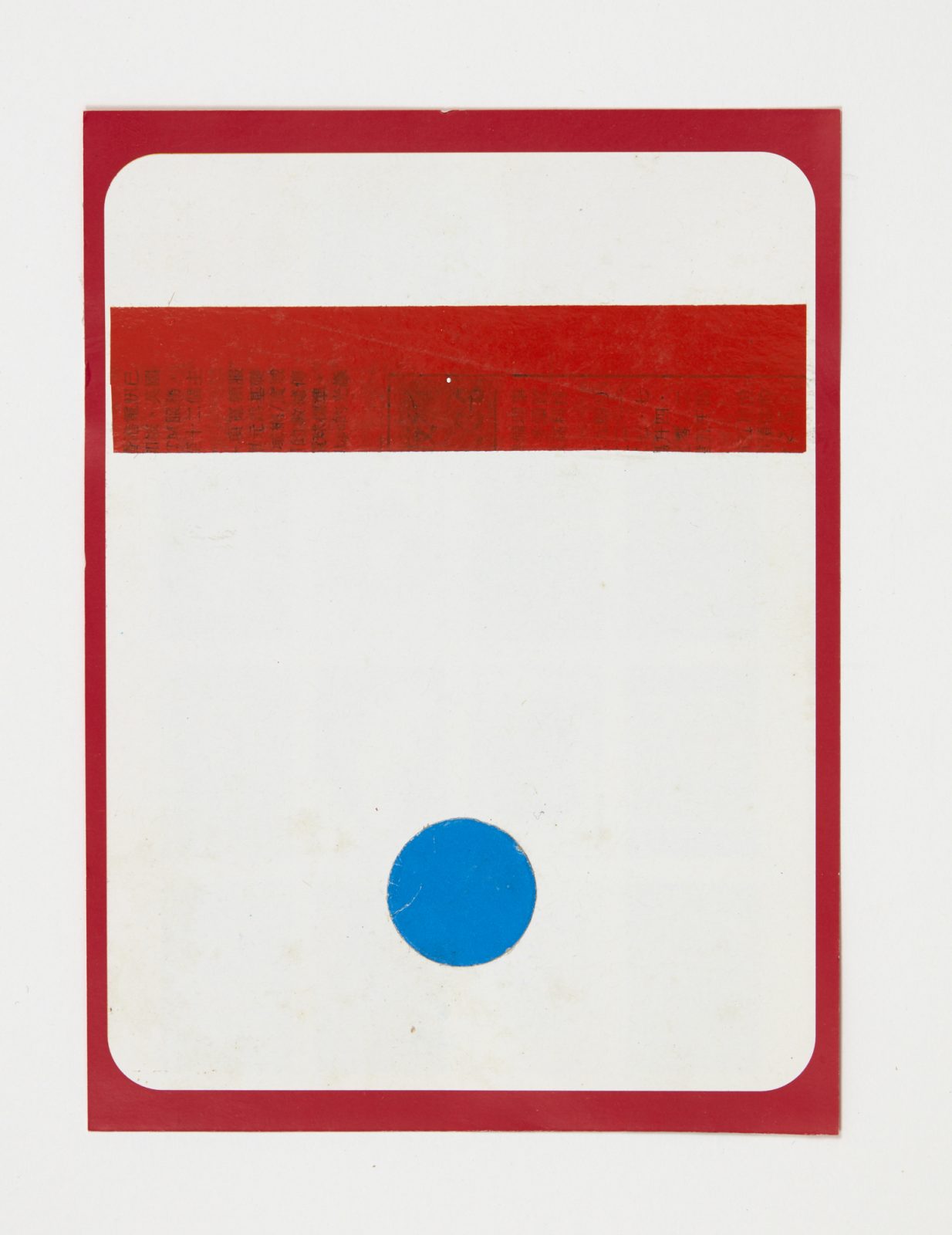

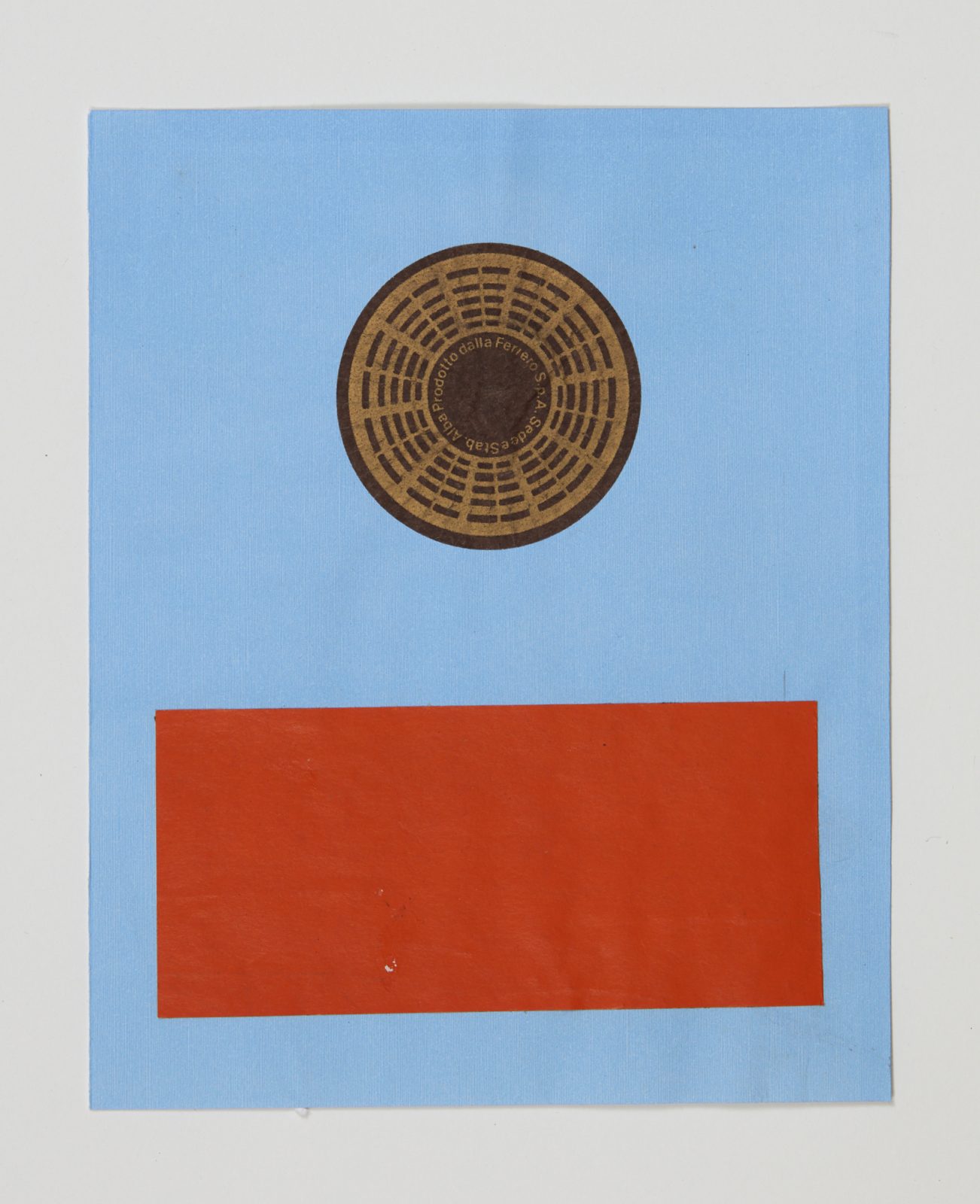

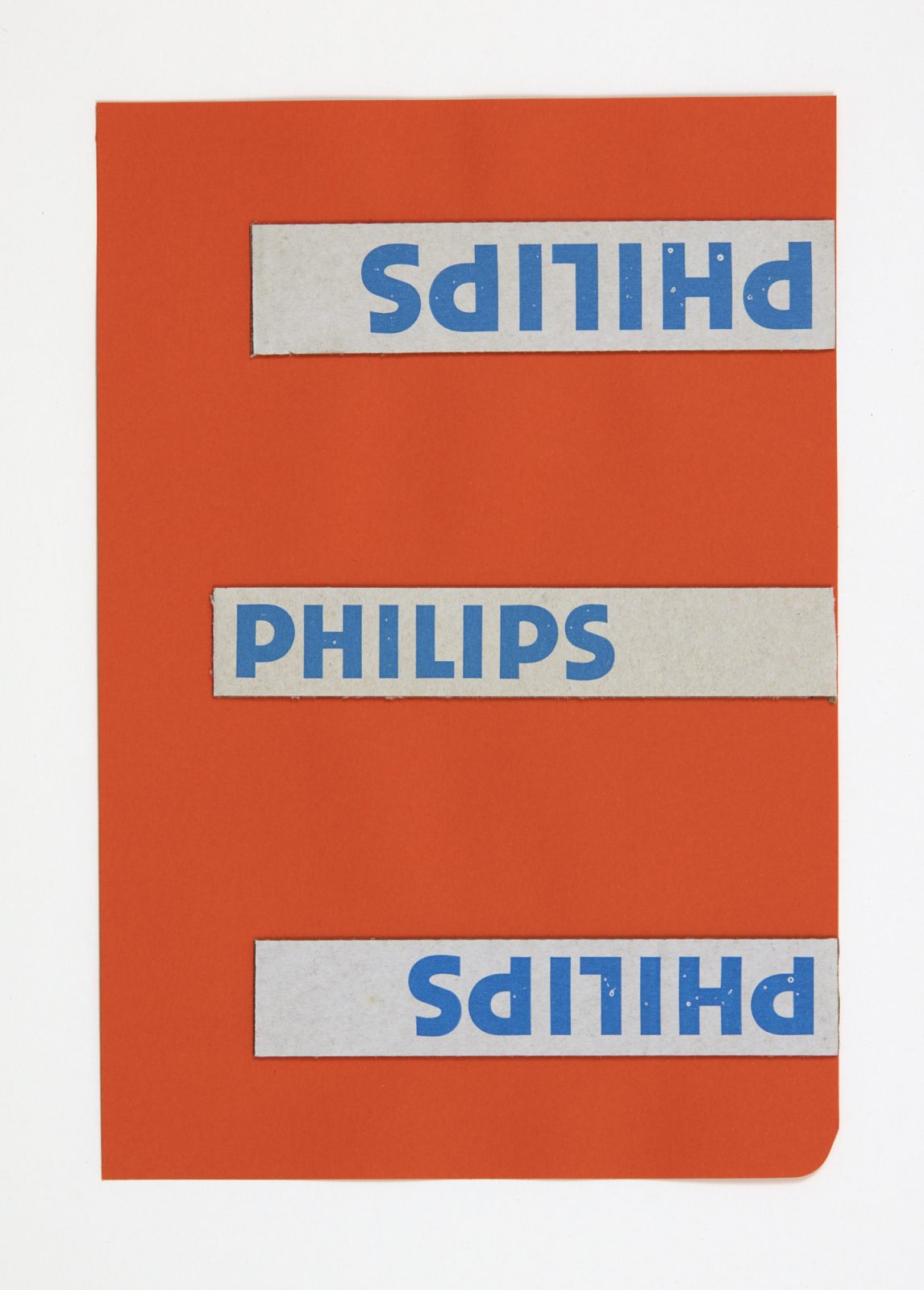

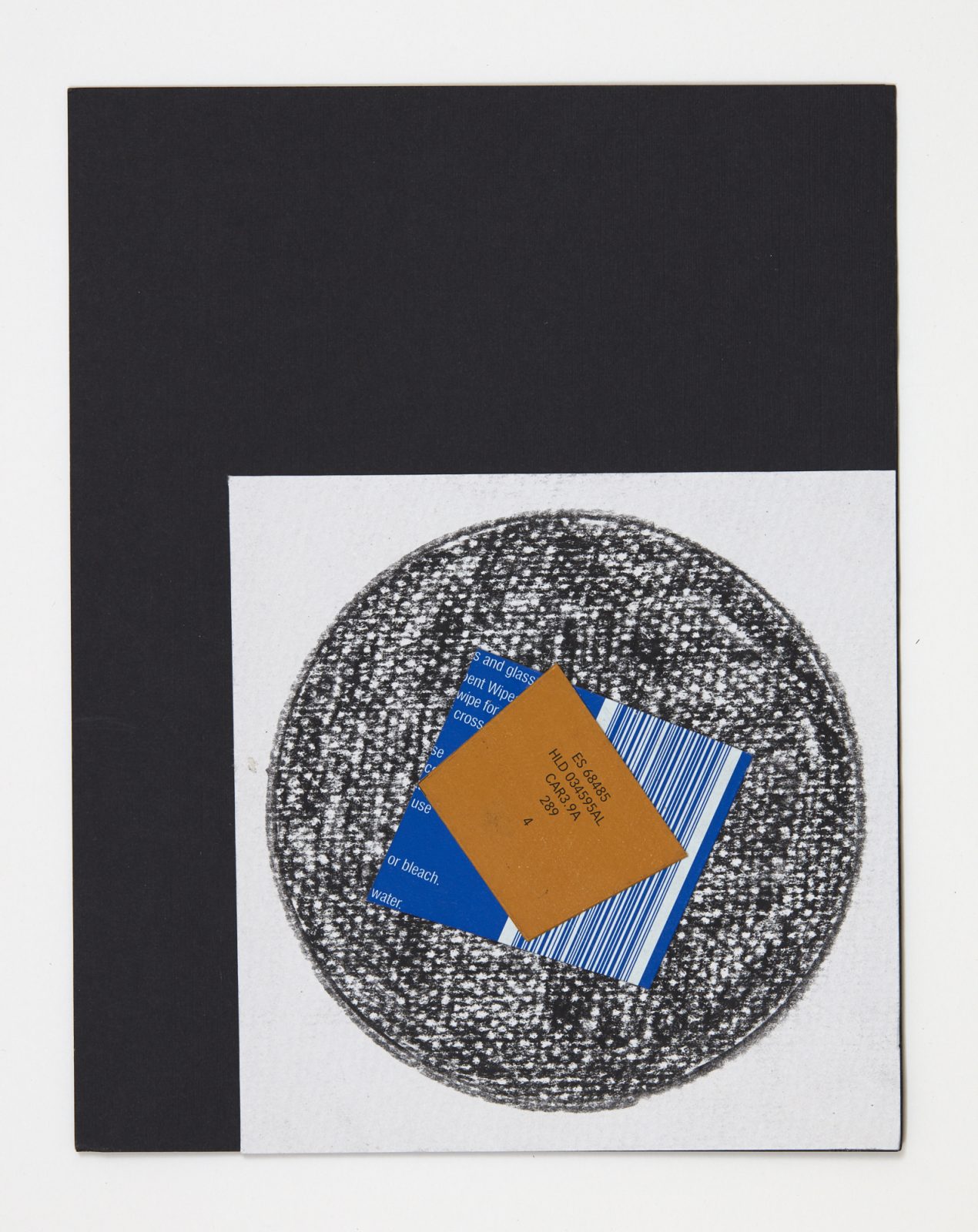

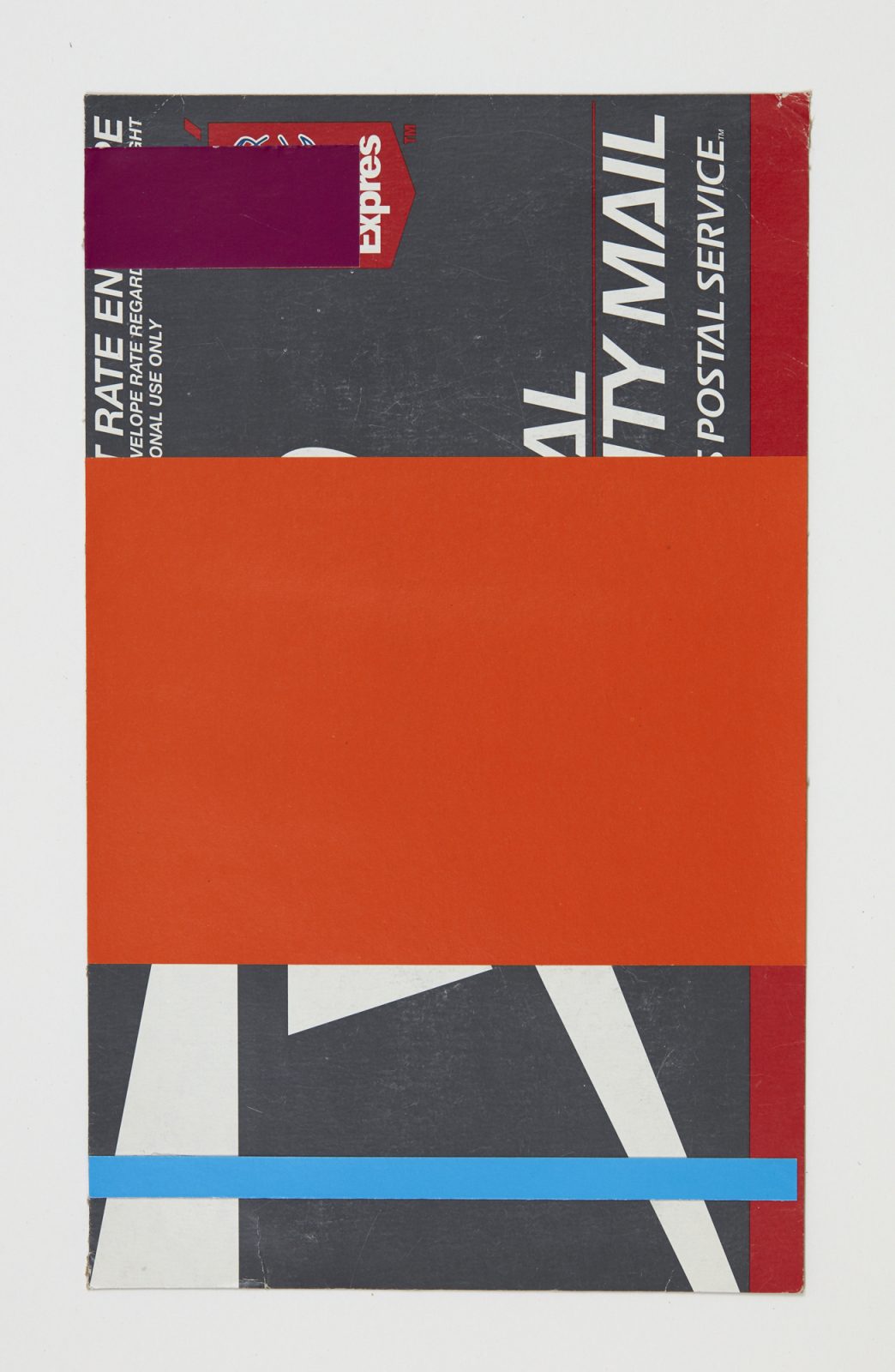

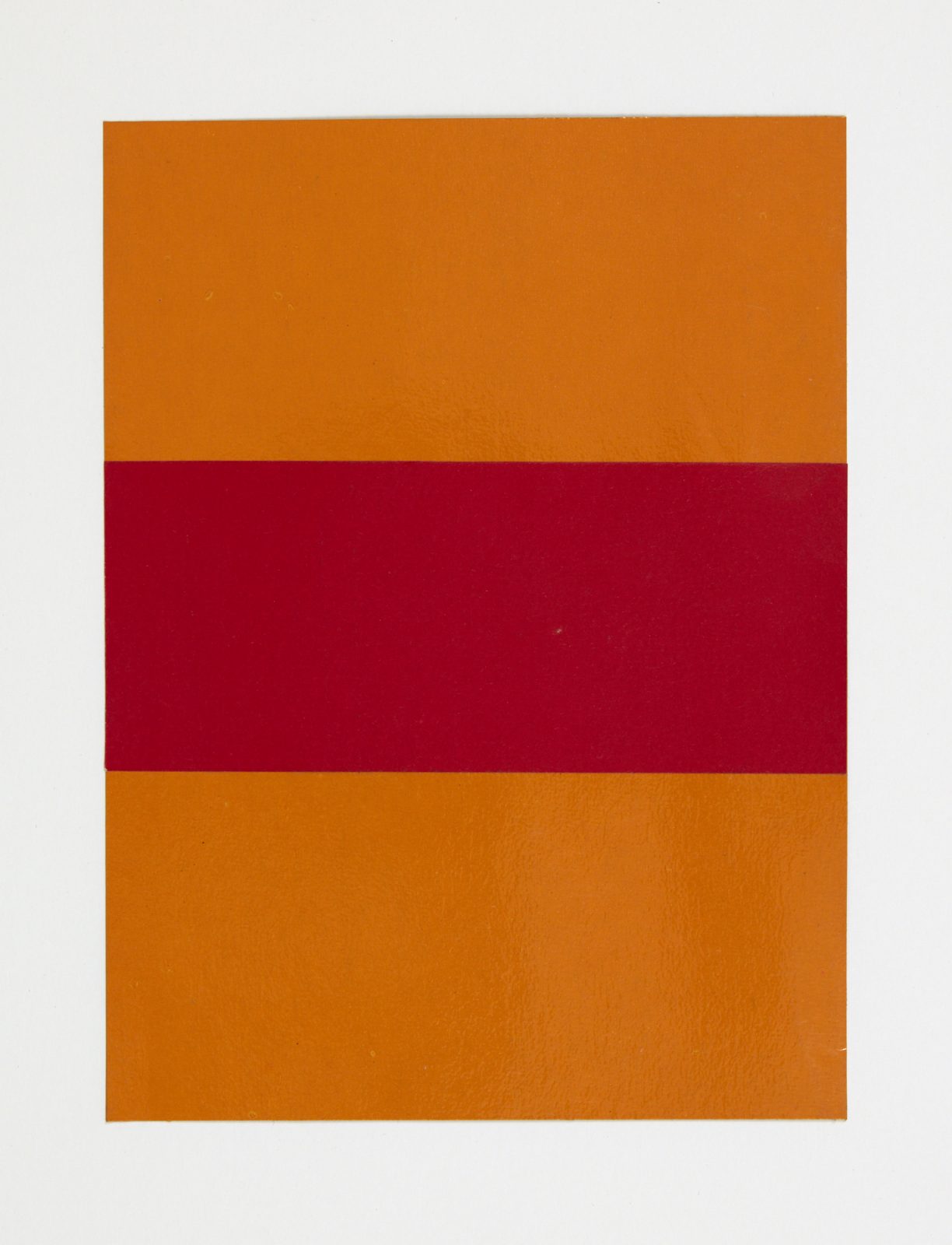

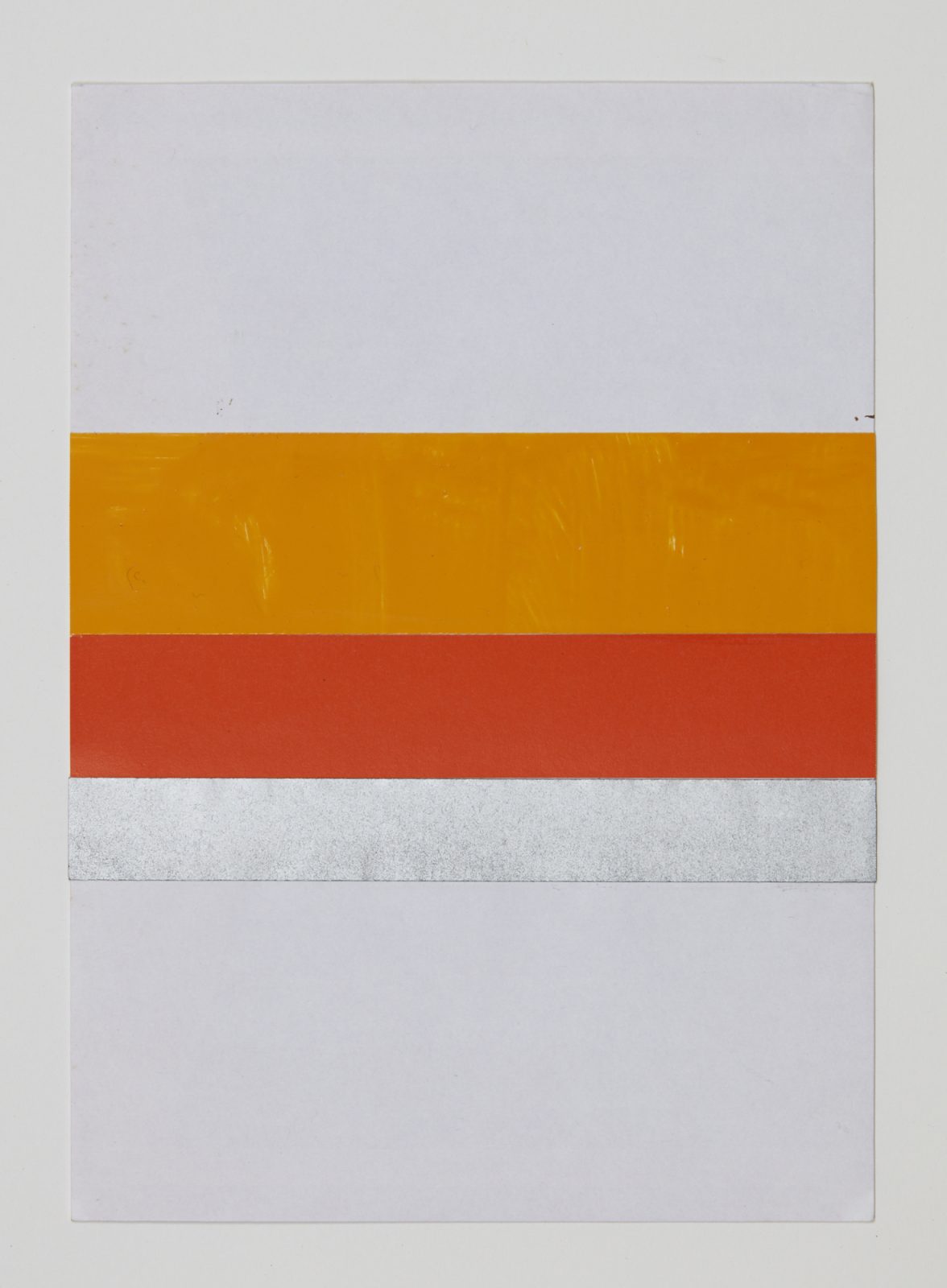

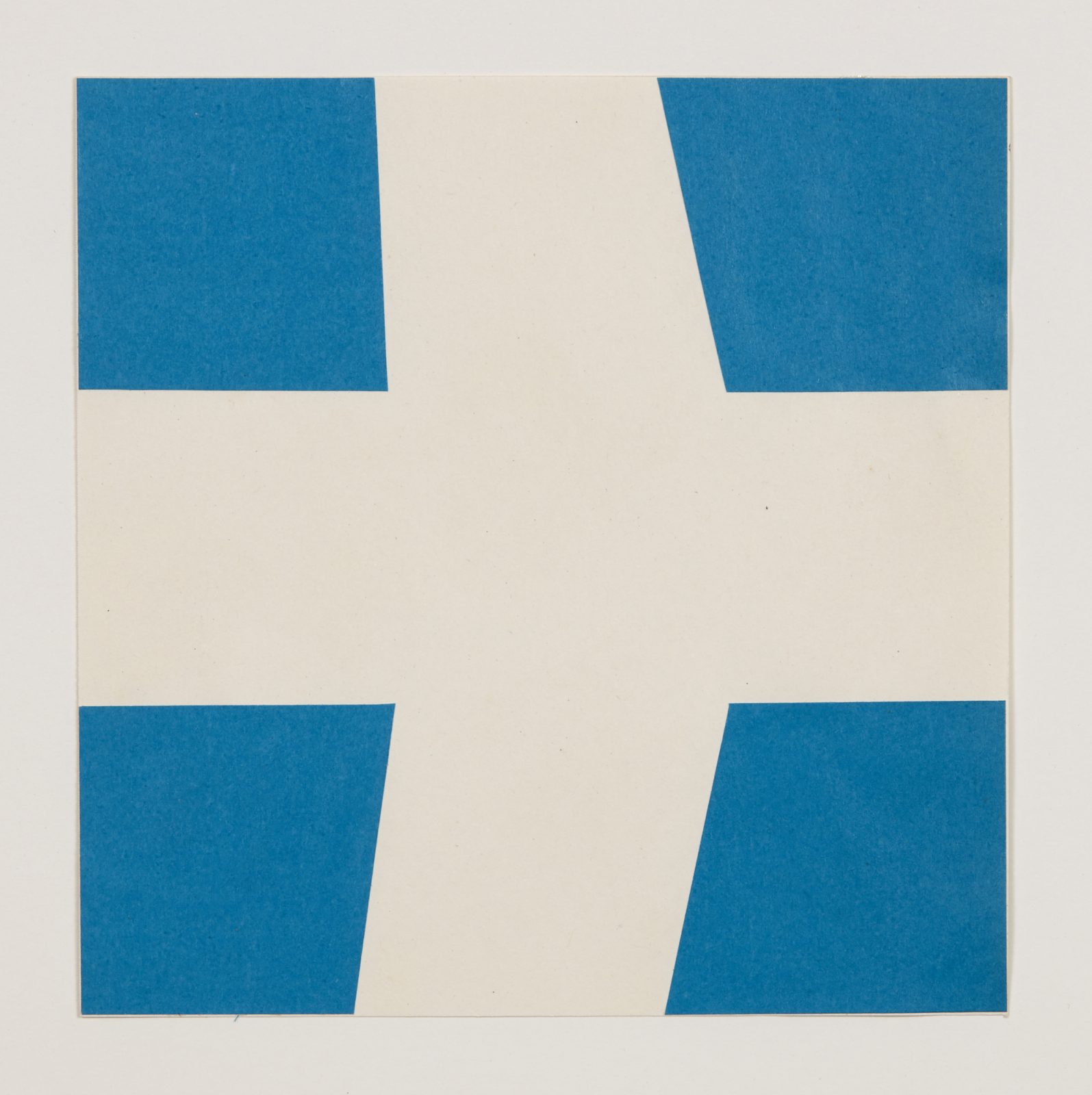

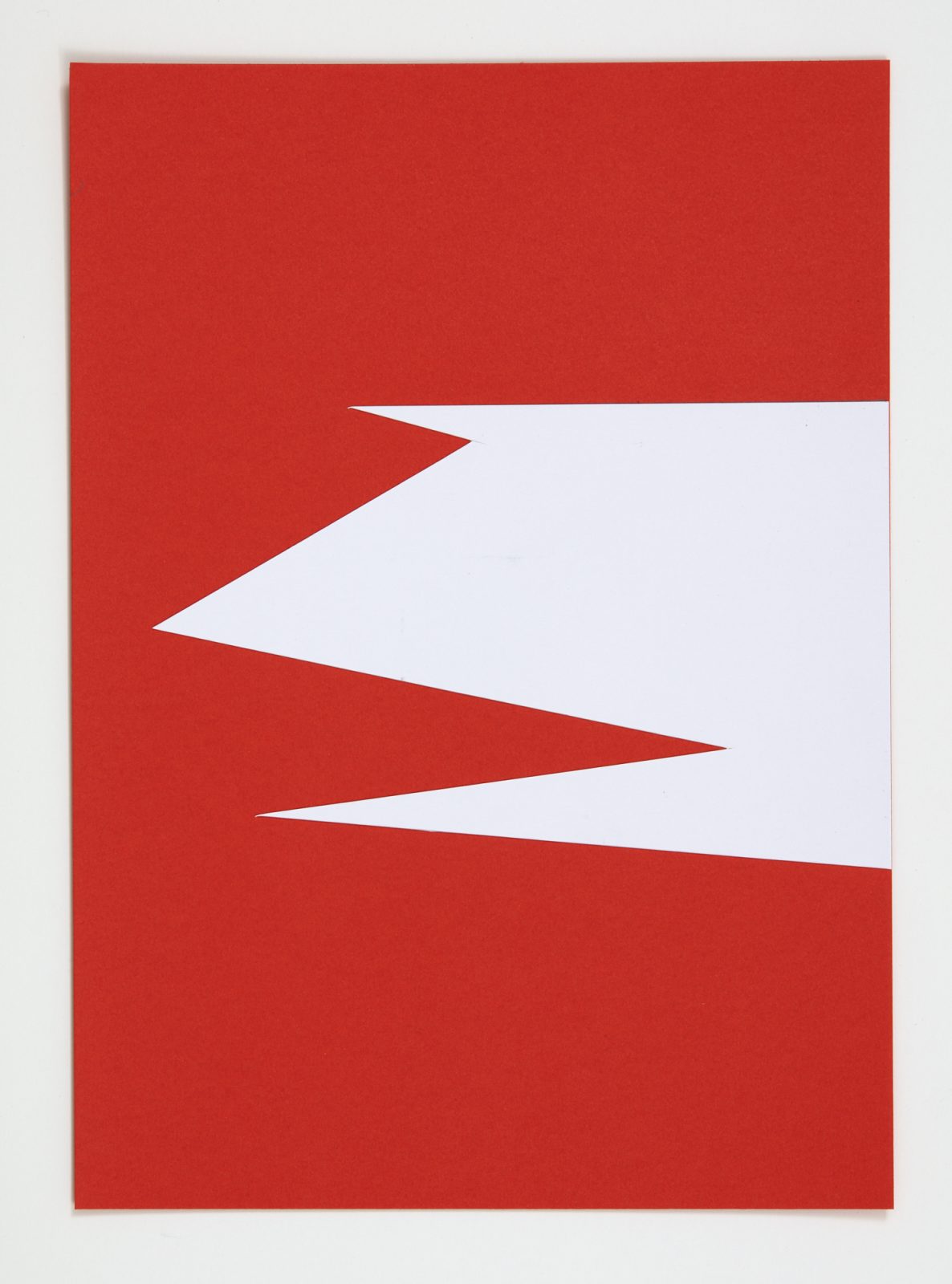

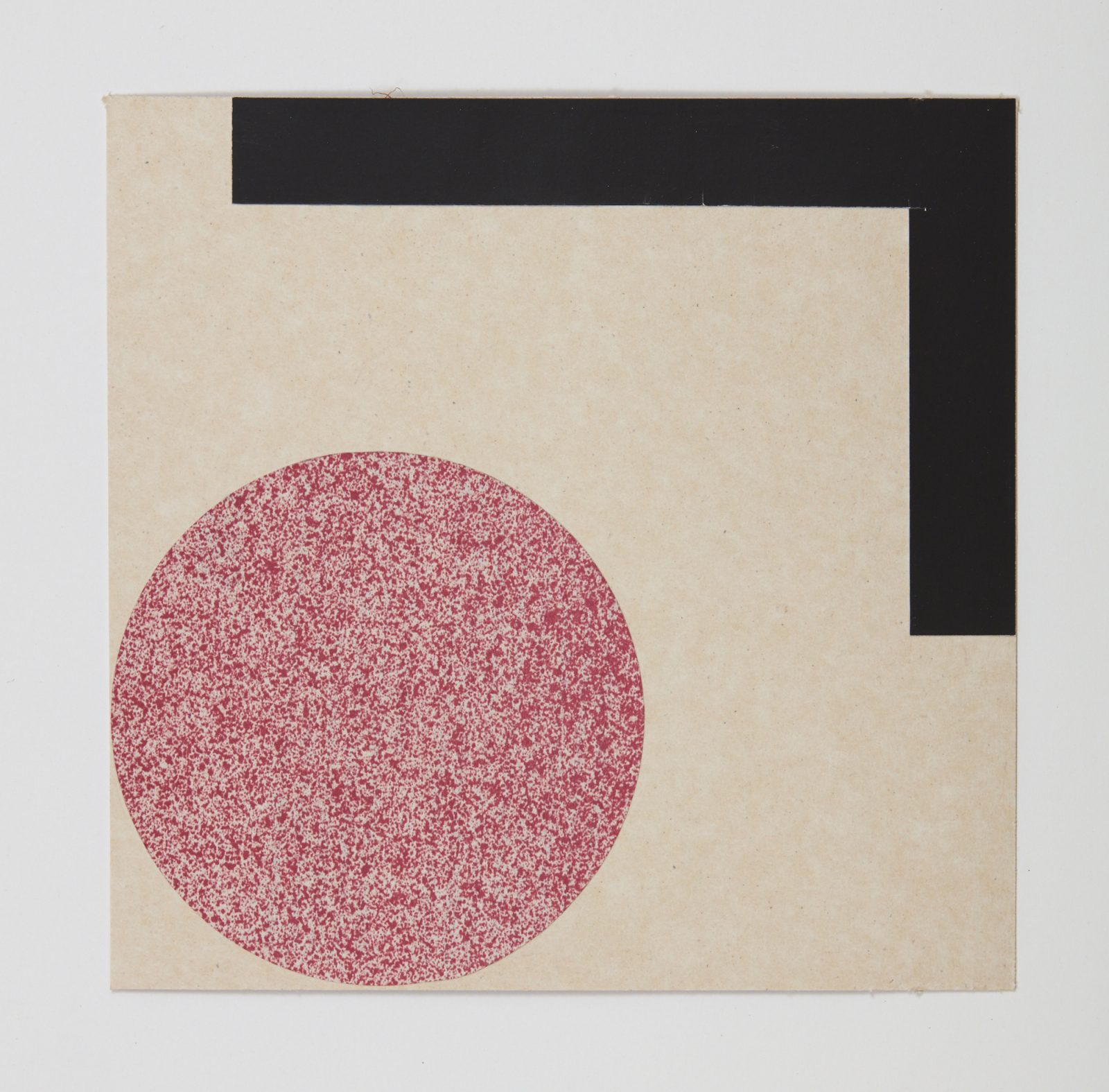

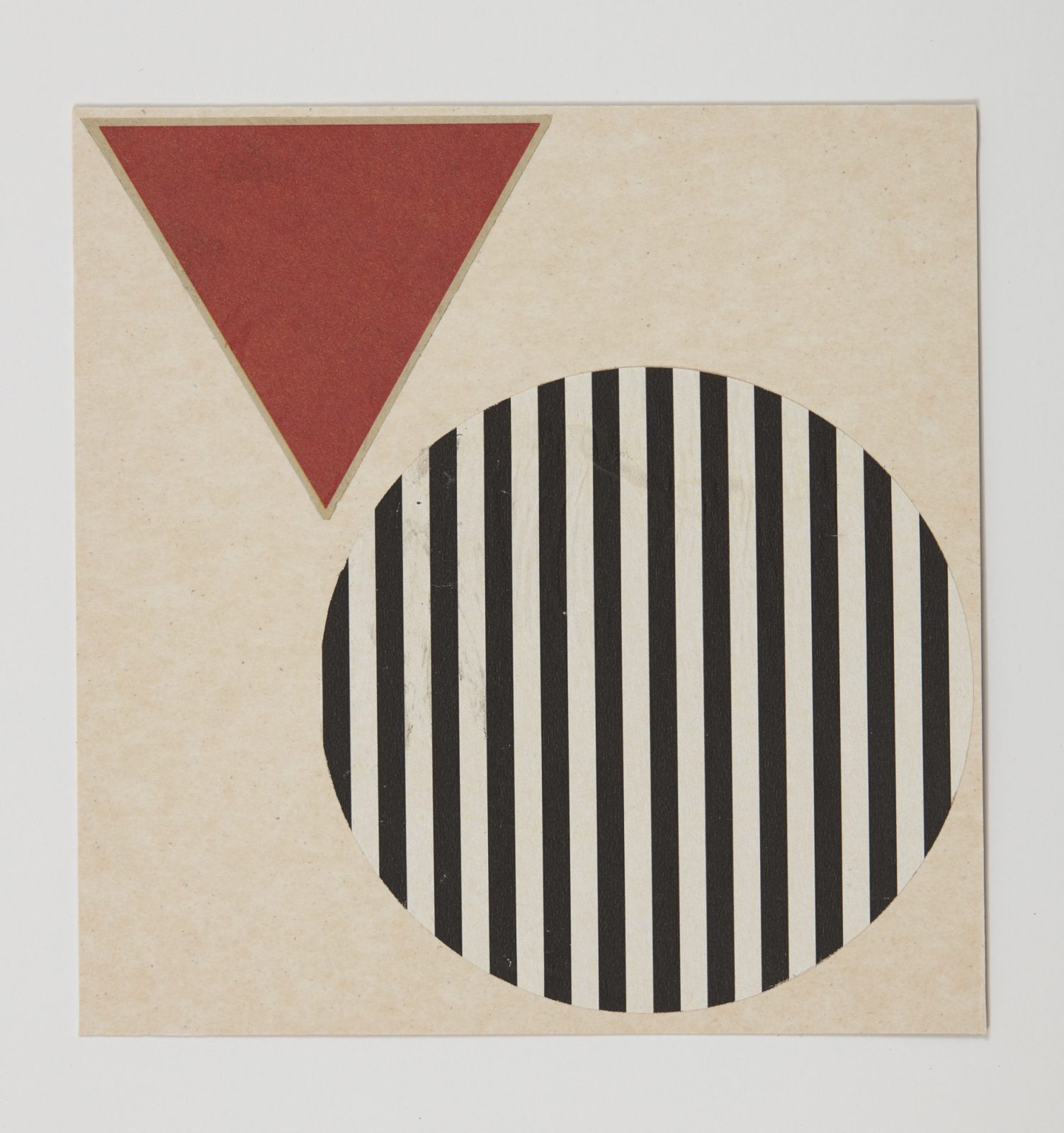

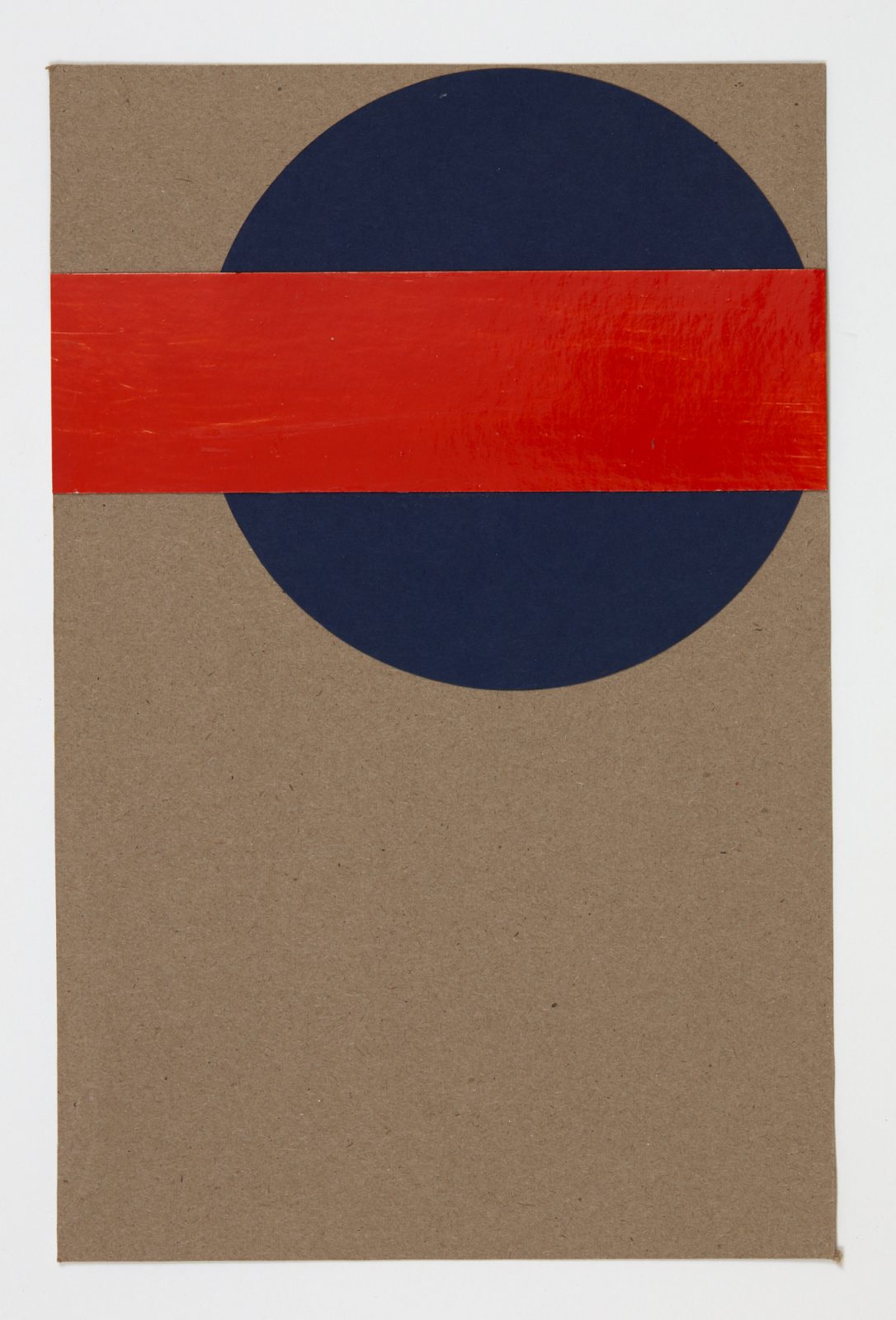

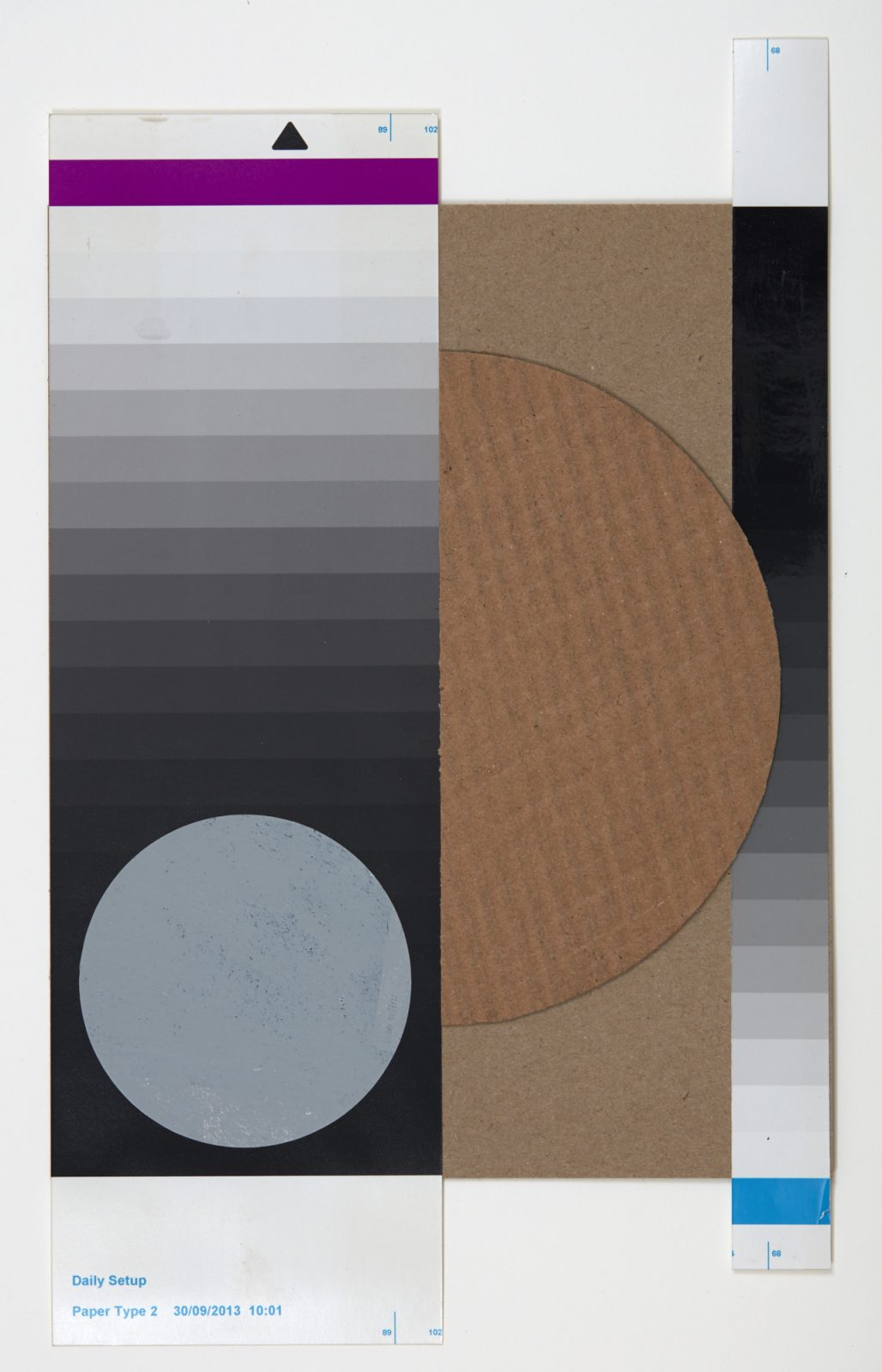

Nixon’s practice mines the visual language and potential meanings of minimal geometric abstraction, which also emerged in the early Twentieth Century around the same time as collage. Nixon’s signature orange features heavily here, along with accents of silver, as a kind of index to his paintings. Primary forms also recur: circles, triangles and crosses, to regions of vivid monochrome, both featured in Nixon’s oeuvre and in Modernism’s ‘greatest hits.’

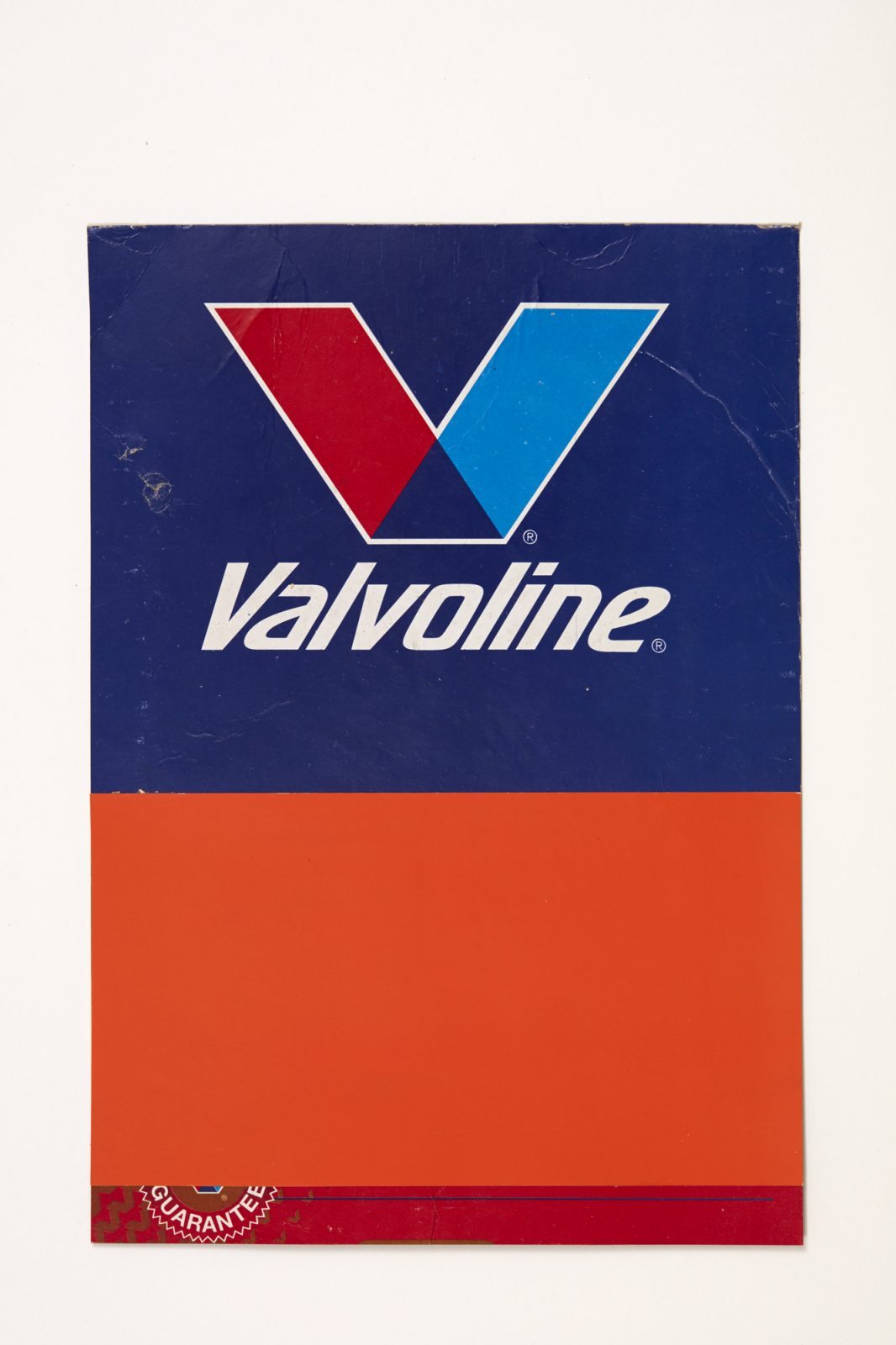

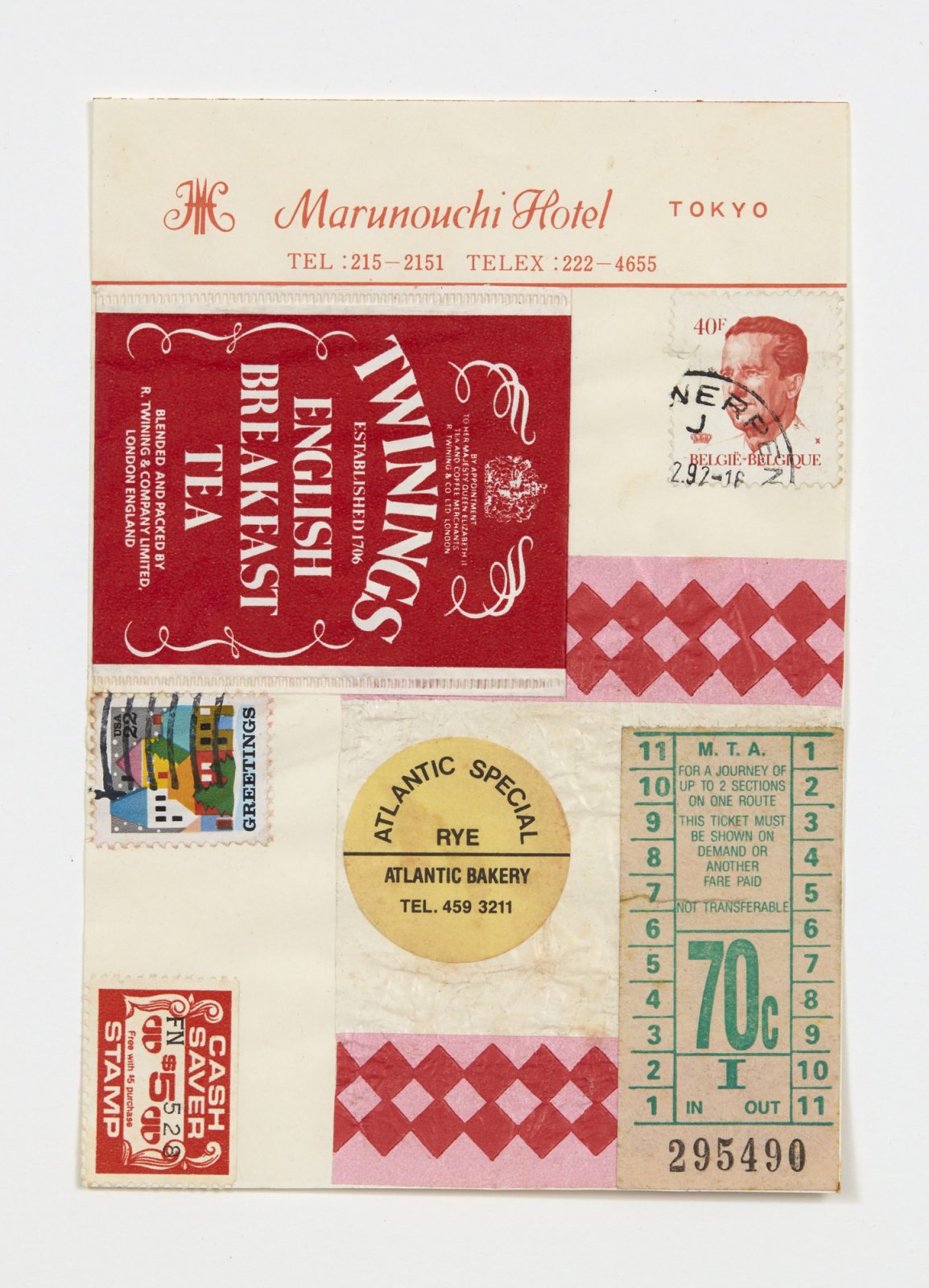

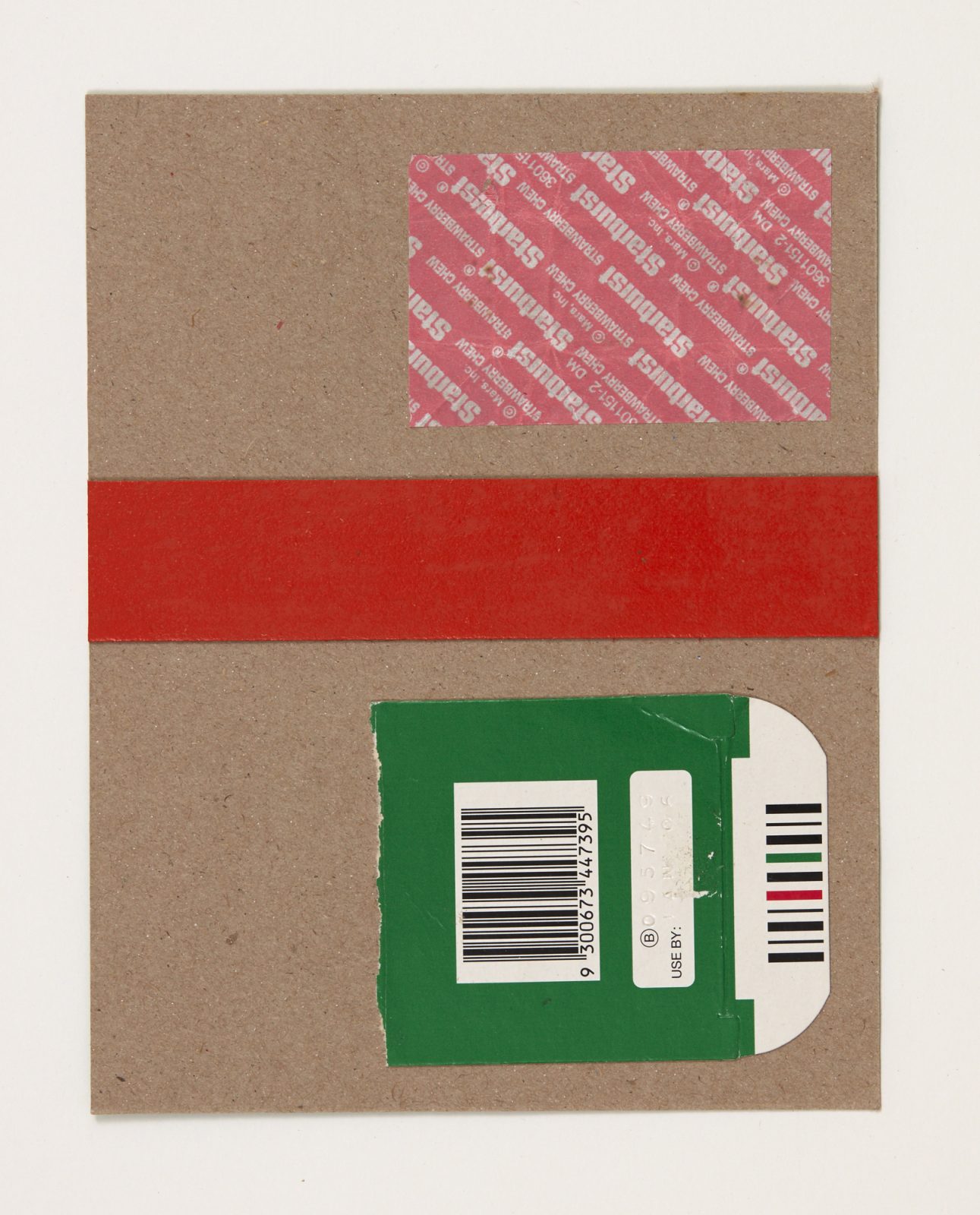

Nixon’s collages feature a diverse range of found paper-based materials with scarcely a lick of paint: Swiss chocolate wrappers, stamps, newspaper clippings, Nippon Paint palettes, coloured paper and card, sections of his own photographs, a return ferry ticket to Rangitoto Island, an invitation to his exhibition in Tubingen, Germany. They intuitively document and recycle traces of the artist’s travel through domestic, local and international spaces, from the kitchen to the other side of the world. Suitably, one is constructed on top of an envelope.

His collages reflect on the utopian promises of early Modernist abstraction, and find a corollary in those made by the advertising of consumer goods. He finds a congruence in red and green monochrome circles and a photograph of beans. He finds the likeness of a painting in the design of a paracetamol box, a pleasing geometry in the black and white barcode laid over Panadol green. Modernism in the medicine cabinet.

As we spoke about his work, he found interest in the circles printed on the cover of my notebook. With Nixon, it seems, art can be sourced everywhere.

Emil McAvoy, Auckland, April 2017

Mixed media collage

205 x 195 mm

Mixed media collage

210 x 146 mm

Untitled, 2015

mixed media collage

245 x 172 mm

Untitled, 2016

mixed media collage

264 x 196 mm

Untitled, 2017

mixed media collage

211 x 150 mm

mixed media collage

158 x 117 mm

mixed media collage

184 x 134 mm

mixed media collage

310 x 210 mm

mixed media collage

138 x 94 mm

mixed media collage

154 x 106 mm

mixed media collage

215 x 166 mm

mixed media collage

235 x 135 mm

mixed media collage

297 x 210 mm

mixed media collage

180 x 145 mm

mixed media collage

218 x 216 mm

mixed media collage

257 x 173 mm

mixed media collage

143 x 120 mm

untitled, 2009

mixed media collage

287 x 210 mm

Untitled, 2009

mixed media collage

297 x 210mm

mixed media collage

297 x 210 mm

mixed media collage

280 x 197 mm

mixed media collage

230 x 170 mm

mixed media collage

274 x 191 mm

mixed media collage

154 x 106 mm

mixed media collage

220 x 160 mm

Untitled, 2002

mixed media collage

176 x 130 mm

mixed media collage

188 x 151 mm

mixed media collage

250 x 250 mm

mixed media collage

210 x 146 mm

mixed media collage

297 x 210 mm

mixed media collage

280 x 210 mm

mixed media collage

223 x 152 mm

mixed media collage

164 x 128 mm

mixed media collage

220 x 172 mm

mixed media collage

246 x 150 mm

mixed media collage

297 x 210 mm

mixed media collage

179 x 131 mm

Mixed media collage

297 x 210 mm

mixed media collage

230 x 160mm

Untitled 2011

mixed media collage

282 x 235 mm

mixed media collage

140 x 140 mm

Mixed media collage

297 x 210 mm

Mixed media collage

297 x 210 mm

Mixed media collage

169 x 172 mm

mixed media collage

173 x 168 mm

mixed media collage

215 x 135 mm

mixed media collage

289 x 187 mm

mixed media collage

340 x 227 mm

mixed media collage

210 x 147 mm

mixed media collage

150 x 150 mm

mixed media collage

118 x 140mm

mixed media collage

203 x 202mm

mixed media collage

210 x 175 mm