Jude Rae

Recent Paintings

26 September - 26 October 2019

Tethered

I believe that nothing can be more abstract, more unreal, than what we actually see. We know that all we can see of the objective world as human beings, never really exists as we see and understand it. Matter exists, of course, but has no intrinsic meaning of its own, such as the meanings that we attach to it. Only we can know that a cup is a cup, that a tree is a tree – Giorgio Morandi, 1960

Jude Rae’s paintings are remarkable for being paintings. Not photographs or sculptures, they are not embedded in the world but interested in revealing an experience of it. Paintings are a very specific kind of object. They are two-dimensional, yet depict space; your eye can reach into a painting, move around inside it. They are specific also for the way they exist within a rarefied history of objects, each painting just one line in a conversation that spans thousands of years and encircles the globe. In the case of Rae’s still lifes, we understand them within the tradition of realism, a section of the conversation characterised by honesty and precision. While realism is concerned generally with the depiction of ordinary life, the still life could be considered the most mundane genre of all, historically seen to occupy the lowest rung in the hierarchy of genres. Yet still lifes have always been painted, always been popular, their popularity testament, perhaps, to a universal craving for a stillness only painted objects can offer.

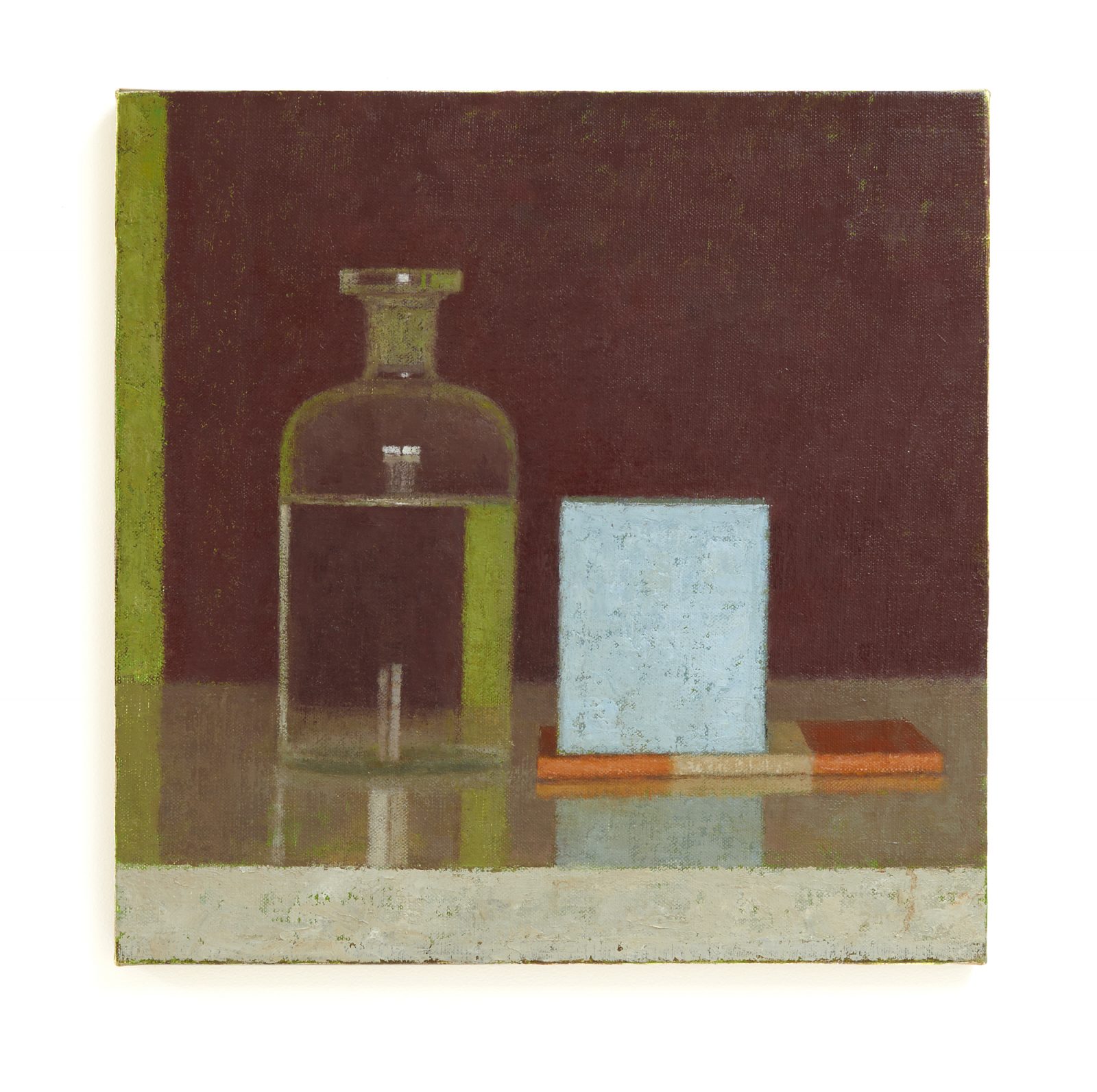

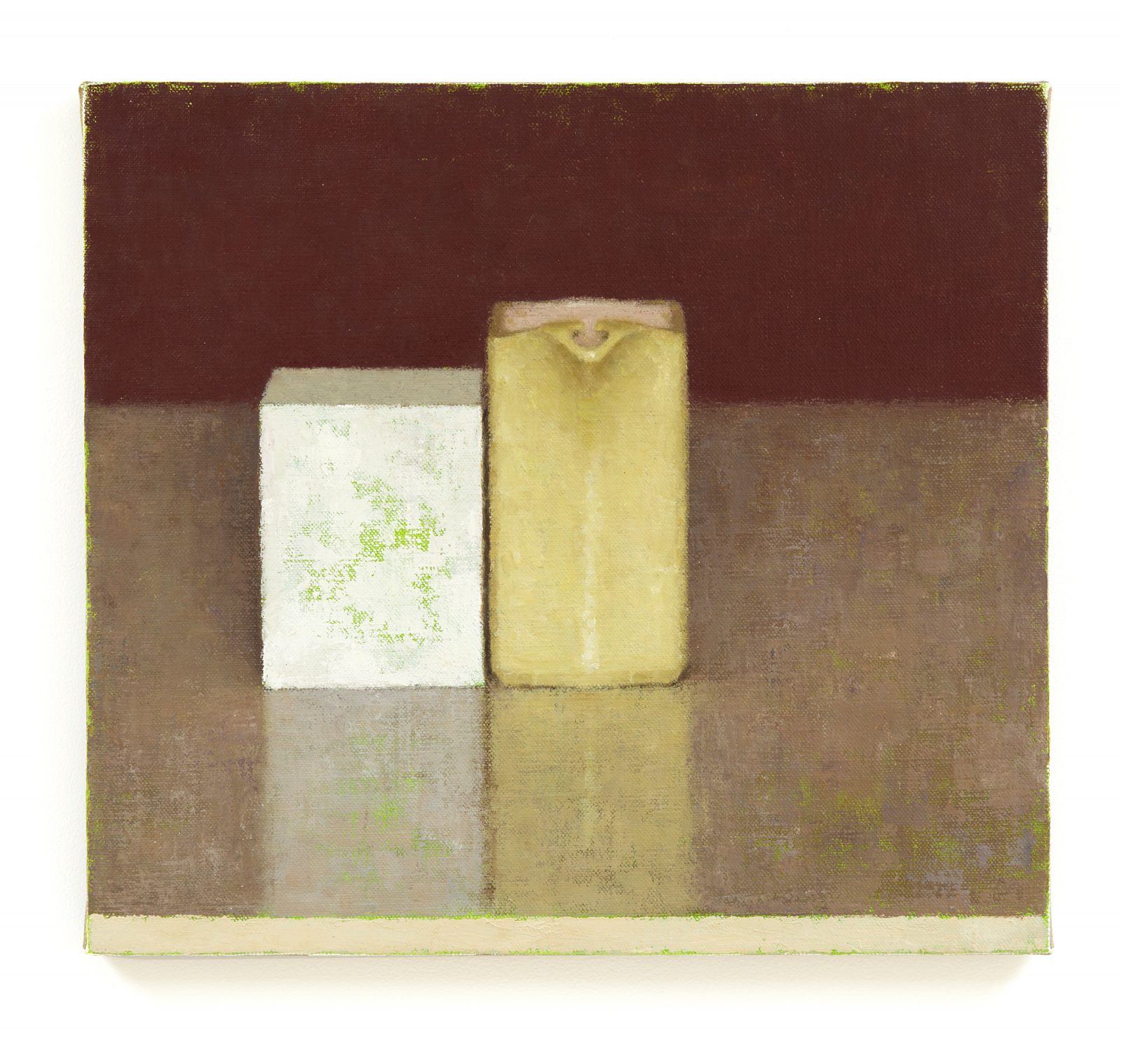

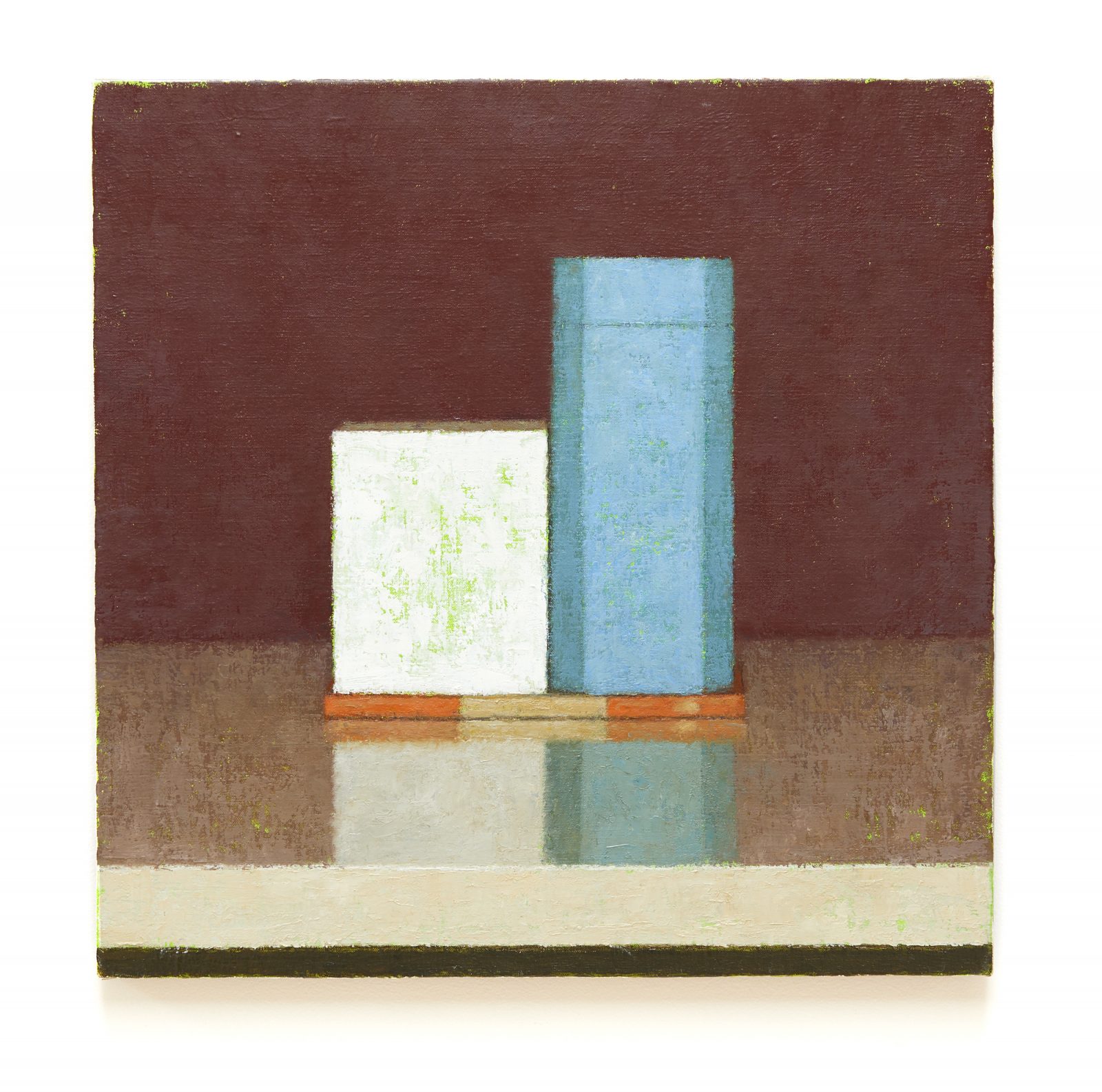

Paintings are more than the sum of their parts. When we are shown a painting, we can say it is a painting, but that would tell us nothing of its meaning, which comes more from the effect it has upon us than the content we can find within the frame. Paintings are not like the ‘matter’ Morandi speaks of, for they would not exist had the artist not chosen to render meaning in material. Searching for meaning, we could say Rae’s still lifes allow us to find beauty in utilitarian objects, arrangement and simplicity. However, to leave it here would be to miss out on something far more intriguing. Instead of asking why the artist has chosen to attend to this vase, this block, this gas bottle, we would do better to ask how our experience of these objects has been reorganised. Could the curved cream edge of a ceramic jug ever appear so soft if it were just sitting on the table before me? Under what light would those edges seem to buzz? If I reached out and touched it, would my flesh disrupt whatever charge holds it together, would the softness collapse into liquidity? To stand before SL 398 is to feel a fizzing serenity akin to the sensation of walking along the shore of a lake, negative ions making you feel at once enlivened and at peace.

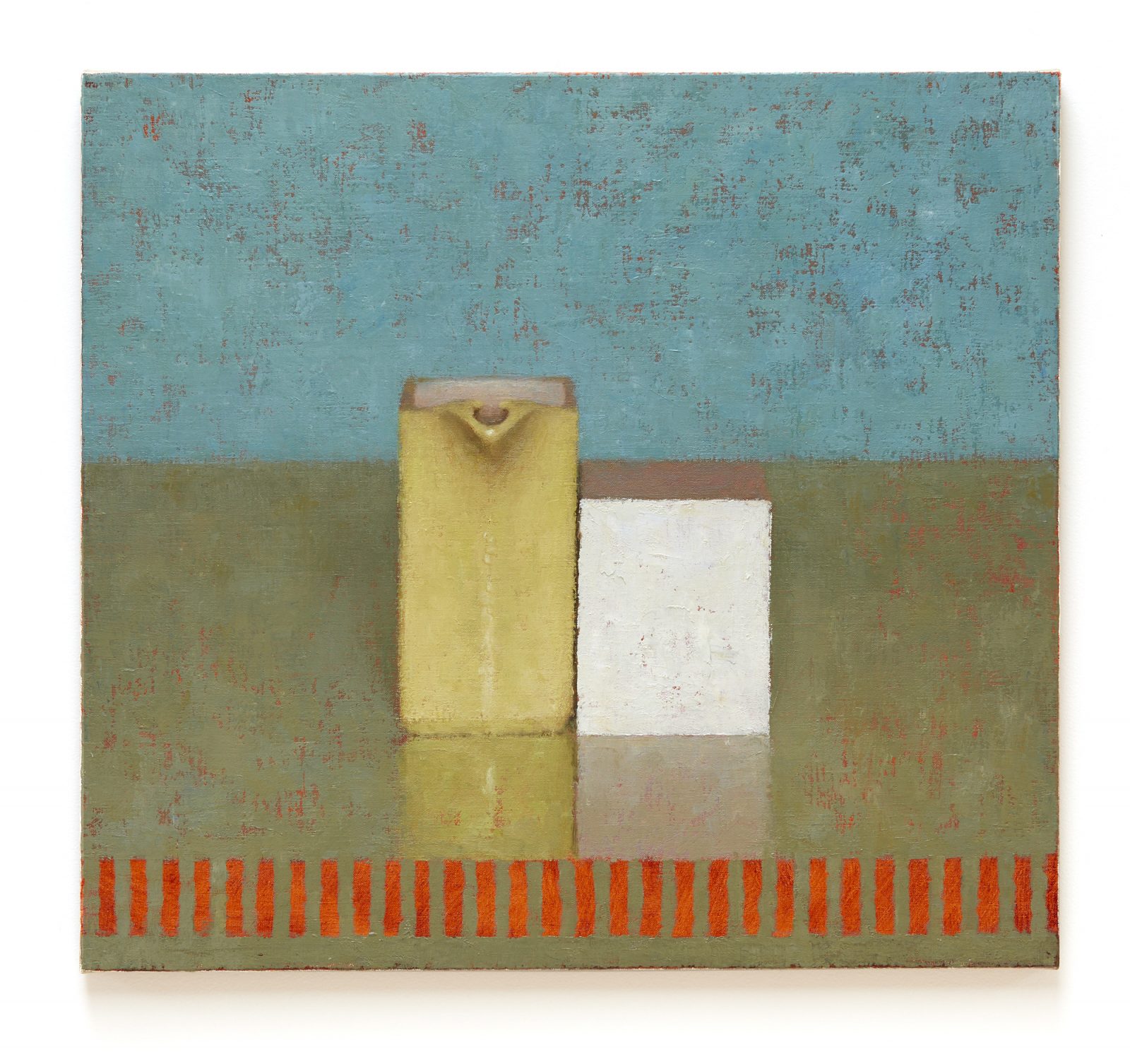

The painting is not the objects it portrays, nor is it necessarily about them. In the case of Rae’s still lifes, the paintings often seem to be about painting itself, for there are moments that feel less about an accurate depiction of the object than about the exploration and creation of forms. In works such as SL 408, the red-and-white horizontal stripes of a squat fire extinguisher are refracted through the octagonal walls of a tall jar, turning vertical as they pass through glass and water, becoming more pattern than object, hinting at the historic flow from still life to the abstract, from the lowest genre of painting to lauded innovation. It is in these moments that the significance of arrangement becomes clear. For Rae, it seems the selection and arrangement of objects is a means to a very specific ends, creating opportunities for forms to slip into abstraction but never fall, always remaining tethered to real world objects and their effects.

In the same way that a writer may discover how they feel about an experience as they write about it, or any person may come to understand themselves more deeply by talking through their emotions to a sympathetic listener, perhaps Rae paints objects in order to make sense of them. The irony being, of course, that in paint, the objects are not themselves; they are changelings, solid forms swapped for visions conjured in dabs of paint. The otherworldly version comes to overpower the original, holding our attention in a way the true tabletop arrangement never could.

And yet we understand these simulacra as the objects they impersonate. We know that a cup is a cup, that a tree is a tree. We understand this not because cups and trees are remarkable, but because they are so very prosaic. Vases, gas bottles, fire extinguishers, those white plastic canisters they often pack honey in. Propagated succulents growing roots in jam jars filled with water, ceramic urns with milky blue glazes, a wavy lipped oyster shell. Some of these objects are complicated to name, but they aren’t complicated to look at, feel and understand. The gaze is wordless and knows exactly what they are.

–Lucinda Bennett, 2019

oil on linen

565 x 565 mm

Oil on linen

510 x 510 mm

Oil on linen

500 x 560 mm

Oil on linen

1220 x 1370 mm

Oil on linen

510 x 510 mm

Oil on linen

560 x 610 mm

Oil on linen

700 x 810mm

Oil on linen

560 x 610 mm

Oil on linen

460 x 510 mm