Rob Gardiner

10 September - 9 October 2010

Though he is now widely regarded nationally as a pre-eminent collector and generous patron, administering a charitable trust he established several decades ago, you may not know that Rob Gardiner was for many years associated with the Waikato Society of Arts, an exhibiting community that helped play a key role in the setting up of Hamilton’s public art gallery – now incorporated into the museum. His role grew out of the fact that he was a committed painter, steadily working since the 1960s, rarely exhibiting, although constantly researching.

After 2002, when he moved from Hamilton to Auckland, Gardiner continued this research, using ideas to do with abandoning traditional supports for drawn or gesturally painted marks and using real objects directly in the exhibiting space. Not thinking about spatial illusion within a picture plane, but spatial reality in the viewer’s space.

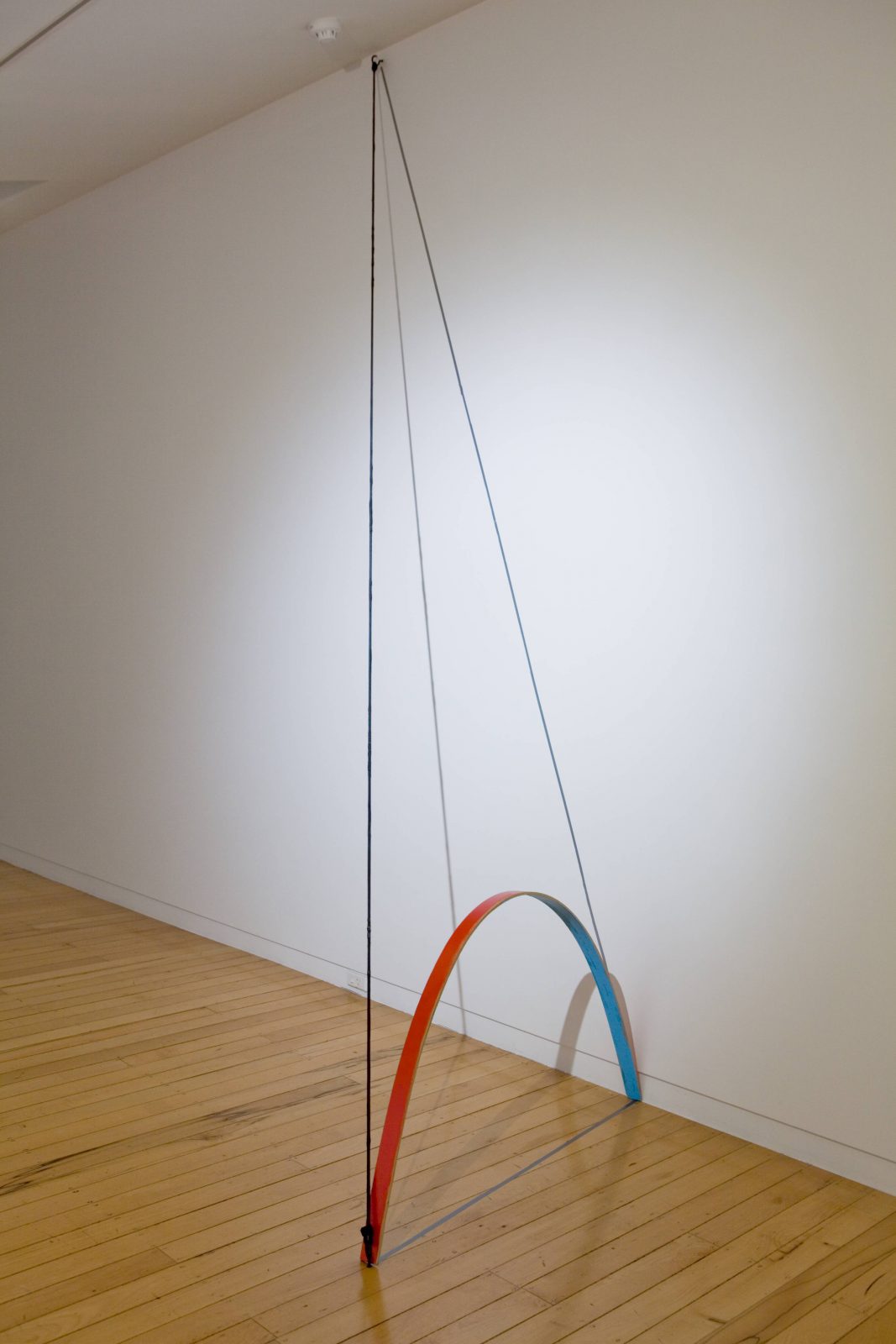

Part of this was driven by the low levels of lighting available in his studio, which made him curious about how controlled illumination affected artworks and the nature of their shadows. The normally hidden means used to hang pictures then became more interesting than the pictures themselves: a primary focus. He separated such taut strings or wires from their function of suspending painted planes so they became independently interesting as palpable lines in space.

The various types of research Gardiner was working on around that time (2004–05) included attaching objects directly to a white wall so that they projected out and cast shadows, having monochrome paintings ‘floating’ in front of the wall with coloured shadows behind, hanging vertical lines of string from horizontally projecting sticks, and glued sticks in simple geometric formations attached to the wall. In 2006 he began incorporating found objects, often discarded detritus from his painting practice, recycling them into relief sculptures which incorporated linear shadows, adjacent to which he could add marks directly on the wall using blue markers and adhesive tape.

In 2007, accessing a nearby Bunnings hardware store, he began pinioning hard and soft items to the studio wall with elastic cord, finding out what could be securely held and what it meant spatially and dynamically. He began thinking like a spread-eagled rock climber with hammer, pitons, carabiners and rope, but instead using hook screws, assorted knots and different varieties of ‘bungy’ cord.

At some point working off only one plane became too limiting, and Gardiner decided to immerse his sculptural elements in ‘real’ space, to suspend them between two or three walls or brace them against a floor or ceiling. Stretched elastic lines that functioned as supports were mingled with rigid wooden poles from which flexible shapes drooped or which pushed against a wall. These created a more immersive space for the spectator, a more participatory relationship – with the projecting elements available to move among or be entered through. Those ingredients included directed shadows that could be broken by the visitor’s body, and other ‘unbreakable’ shadows drawn on the wall. The experience of a walk-in stroll-around drawing.

Working on a new site such as the narrow upstairs Two Rooms gallery, introduces an improvisational aspect to this practice, for while Gardiner can prepare mock ups in his studio, much installation is ad hoc when in a new location. This is because he doesn’t attempt to reproduce an old work, via say a photograph – only using his memory of it as a starting point. He knows the new space will always be different, with unexpected requirements.

Gardiner also uses an appealing, modernist ‘truth to materials’ ethos where he doesn’t disguise anything. He doesn’t try to convince you that the poles are the same as the stretched lines by covering them with the same colour, though at times you might, from certain distances, be confused. Both appear to be rigid. Nor does he try to hide the screw-on hooks in the wall by making them smaller and inserting them into holes – as he could. Instead he exposes their given properties. He doesn’t want to create a mystery by hiding his process, but finds delight in the effect of light on things suspended in mid air and the resulting shadows on the wall

The smaller wall sculptures have developed also. Now decidedly random and entangled – with their interwoven mix of loose wire, netting, shadows and wall drawing – they are more organic and less crystalline, curved and tumbling; not taut and brittle. Something strangely indeterminate on the wall – to stand back from, but remain close to.

– John Hurrell

Elastic cords, wooden poles, particle boards, acrylic paint, tapes, hooks and shadows.

size variable

Elastic cords, wooden poles, particle boards, acrylic paint, tapes, hooks and shadows.

size variable

Elastic cords, wooden poles, particle boards, acrylic paint, tapes, hooks and shadows.

size variable

Elastic cords, wooden poles, particle boards, acrylic paint, tapes, hooks and shadows.

size variable

Elastic cords, wooden poles, particle boards, acrylic paint, tapes, hooks and shadows.

size variable

Elastic cords, wooden poles, particle boards, acrylic paint, tapes, hooks and shadows.

size variable

Elastic cords, wooden poles, particle boards, acrylic paint, tapes, hooks and shadows.

size variable