Robin White

Something is happening here

22 September - 21 October 2017

What it is to dwell among friendly things.

Both the sea and Homer – all is moved by love.

To whom should I listen? Homer now draws still,

And the black sea rumbles, orating,

And with a heavy crash, draws up beside the bed.1

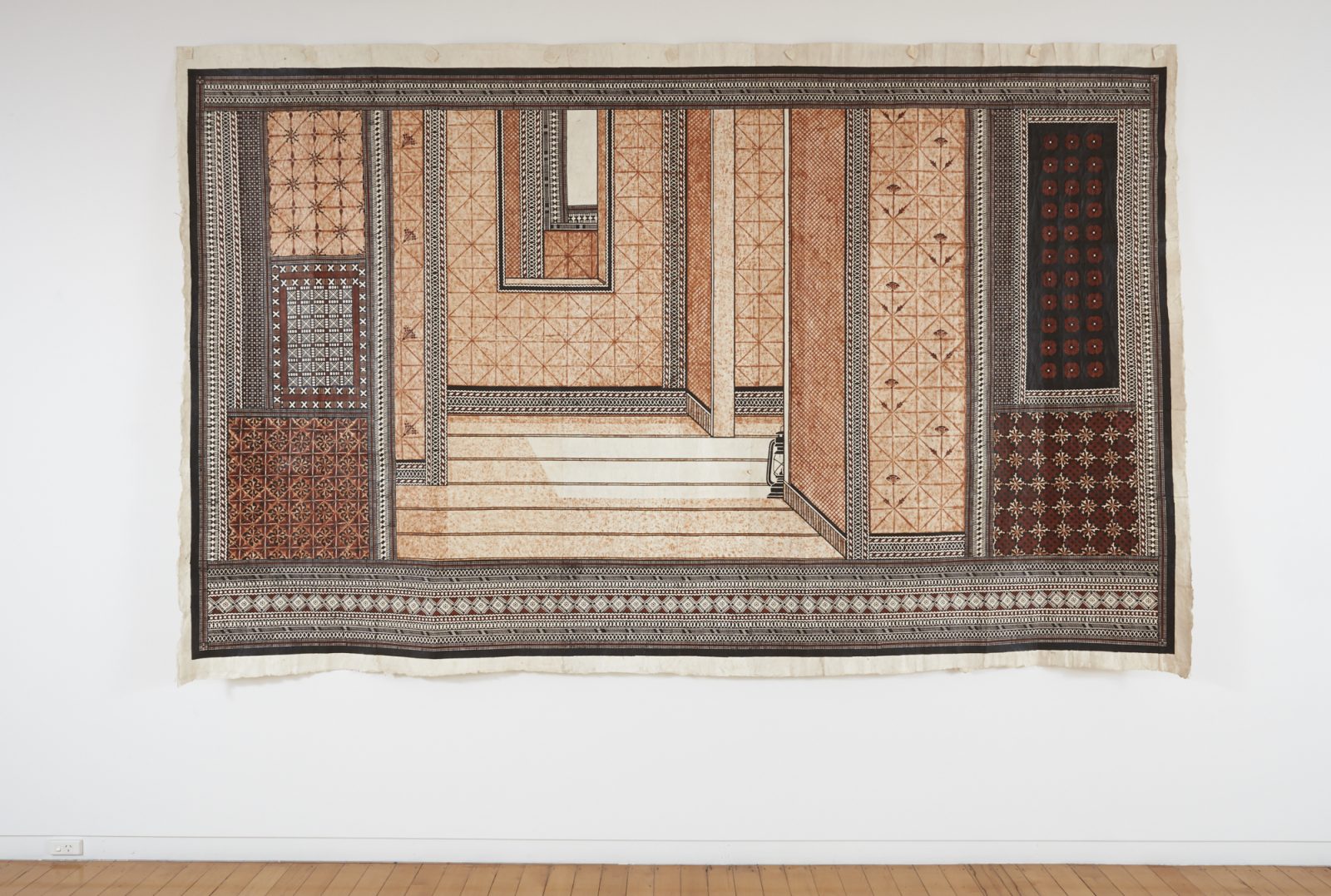

In recent years, some of Robin White’s largest paperbark works have focussed on vast oceanic spaces, particularly in the wake of a 2011 voyage to the Kermadec islands and Tonga. Among the creative yield of that expedition were three tapa works, each measuring 25 square metres. In contrast to those epic evocations of two-dimensional, map-like space, White’s latest suite of works – masi made in Fiji during 2017, with Tamari Cabeikanacea and Ruha Fifita – concentrates on intimate subjects drawn from domestic interior and still life.

Despite their radically different spatial treatments, the oceanic works and her recent productions explore similar notions of sacred space and philosophical / social / ecological equilibrium. As with the Kermadec works, Robin’s newest creations trace processes, cycles and migrations within the human and non-human world. Contained inside a cubic pictorial space not unlike a shipping container, the walls and panels of the recent masi are patterned with flowers, plant-life and flying fish. Lizards scuttle up and down – a kind of living wallpaper. Of the imagery, sourced near and far, she notes that while doves are a familiar motif in traditional Tongan ngatu, the crows depicted are based on the birds indigenous to Mt Carmel in Haifa, Israel, which are ‘revered as the descendants of the birds that brought food to Elijah in his cave’. The other airborne interloper in some of these works is the common Pacific Island butterfly – known as a bebe, in Fijian – formations of which flew outside Robin’s Lautoka workplace, occasionally darting inside while the masi was in progress.

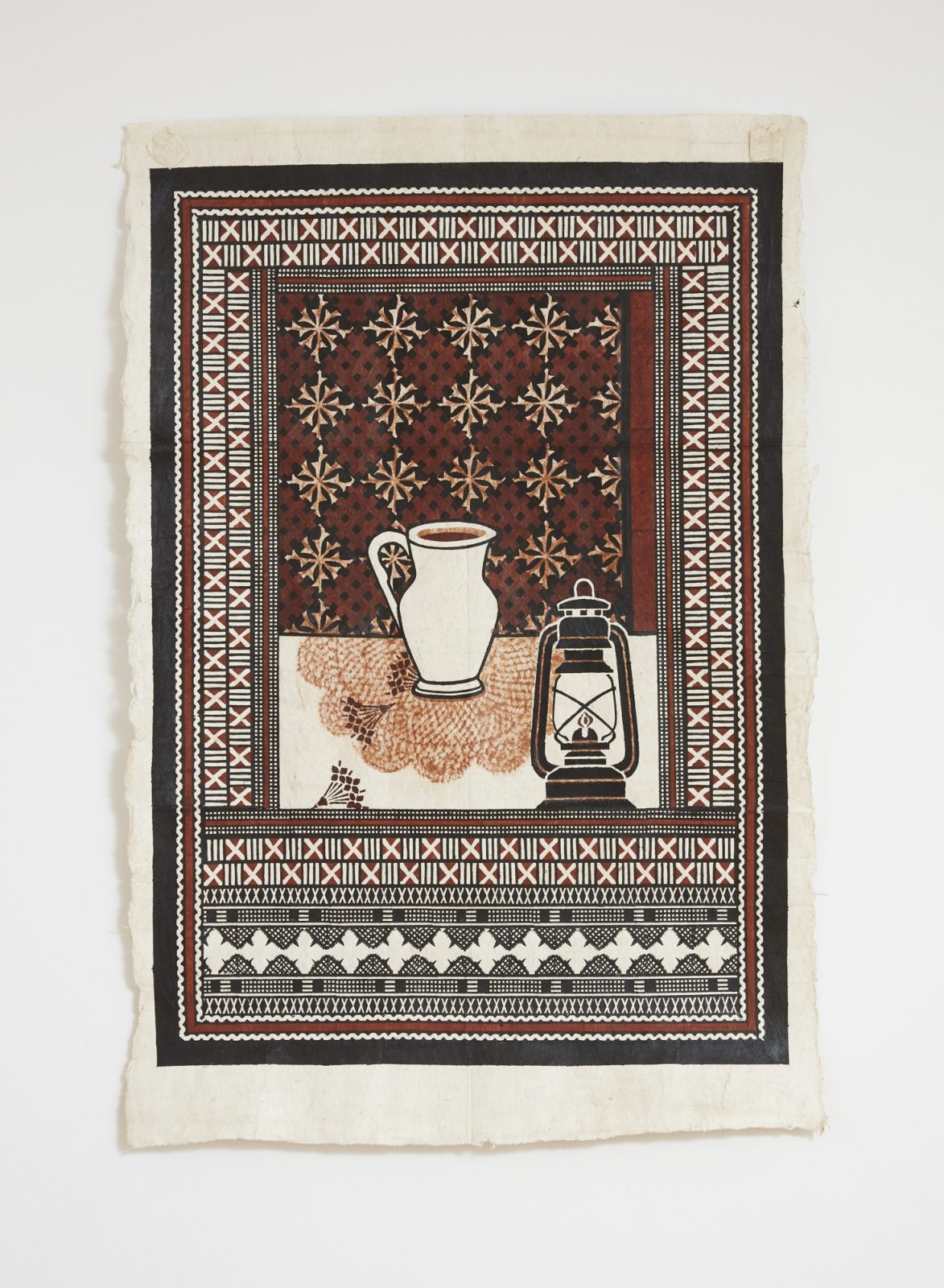

A number of ‘marvellous examples’ of mid-19th century masi which Robin studied in the Fiji Museum collection set the standard, in her mind, for the present project. As well as doing all the stencil work on the paperbark, Tamari Cabeikanacea helped Robin respectfully, but also imaginatively, work within the codes and accepted procedures of masi-making. Other influences on the unfolding work included early Western religious art – witness Duccio’s Last Supper and Fra Angelico’s Annunciation. She also acknowledges Colin McCahon’s 1968 Visible Mysteries series, with its altar-top/still life offerings.

For all their distillation and reticence, however, Robin’s interiors could never be called acts of quietism or retreat from outside realities. They comb the sea of information and data, as they do the physical world, relaying patterns derived from binary coding, braille lettering and digital barcodes. Just as RNZ National plays in her studio in Masterton, and as news of the world filters through to the outskirts of a Fijian town, the room depicted in the masi soaks up – indeed, processes – the humours and tensions of the wider world.

Titled after the refrain in Bob Dylan’s 1965 song ‘Ballad of a Thin Man’ Robin’s Something is happening here also harks back to the song’s opening line: ‘You walk into a room, with a pencil in your hand…’. Like Dylan or, for that matter, any sane and responsive person in the modern world, she feels compelled to remark upon the state of society and the planet. In the room-space of Something is happening here, ‘all distractions have been cleared away, light enters from a partly obscured doorway (or is it the number one, or the letter I in I AM?), and the lamp has been lit. Something is happening here – but we don’t know what it is. Could it be a fresh start?’ Despite much evidence to the contrary, grounds for cautious optimism are offered.

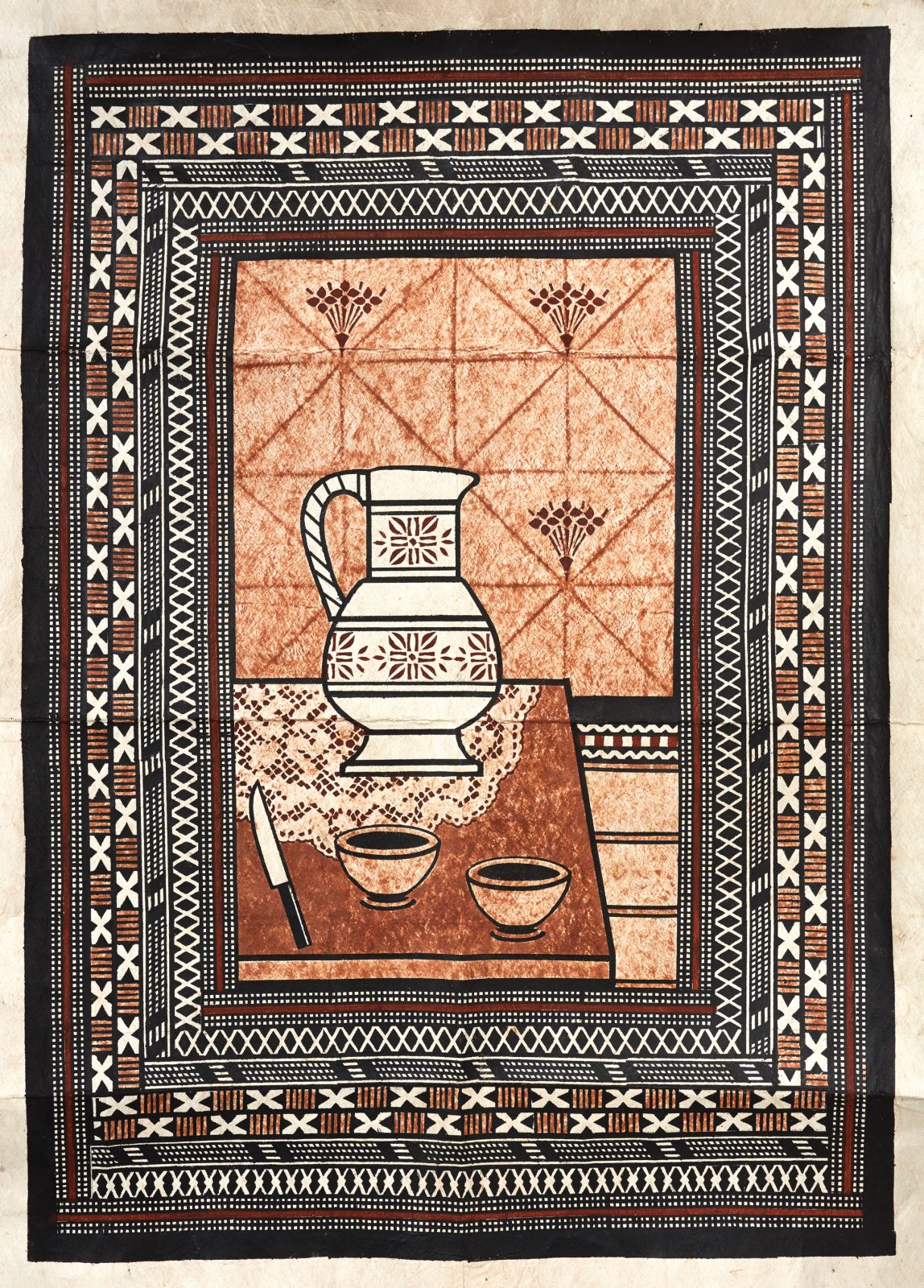

In Robin White’s orderly realm of screens, wall-hangings, blinds and panels, even the smallest pictorial elements are infused with meaning. We encounter the jug (of pure water) which McCahon compared to the Virgin Mary, and the lamp which he likened to the Infant Christ; the dining table is not only an altar, it is a bench, bed or a stand upon which a precious vessel might sit. Importantly, it is also the artist’s work-table and the sacramental site of her art-making.

‘What it is to dwell among friendly things…’ Such is the task of the philosopher, according to Heidegger – to place the human being among enriching, ordinary objects. John Durham Peters, in The Marvelous Clouds; Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media, notes how countless philosophers besides Heidegger have looked to the domestic environment on the grounds that philosophical questions can ‘be fruitfully pursued through detailed attention to shoes, clocks, or the thawing mud’. Still life painters, the metaphysicians of the visual art world, would agree.

Beyond the carefully placed items in these settings, the viewer’s attention is drawn to a particular quality in the space itself. Be it the wild blue yonder or the most confined of domestic interiors, space is not only precious, it is sacred – that is one lesson Robin learnt during her 17 years spent on the remote atoll of Tarawa, Kiribati. In that scenario, the room of the domestic home became inseparable from the wide-open Pacific ecology. And this might be the subtlest point Robin White is making here: that the architectural interior shown in the masi relates directly to the Pacific Ocean itself.

The phrase ‘something is happening here’ resonates even further in this oceanic/family home context – with its arrivals and departures, its visitations, its misadventures and aspirations. Influences from all over the globe wash into the cavity of Robin’s room as they do into the Pacific region. Japanese printmaking is echoed in the screen-like walls and ceremonial design; bowls from a Japanese tea ceremony offer a counterpoint to the adjacent English teapot and cups (which appeared earlier in numerous works exploring the lives of the appropriately named Bell Family, who settled on Raoul Island in the late 19th century). The influence of traditional Indian painting is evident in the spatial choreography, courtly decorum and, more specifically, the vertical arrangement of sugar-factory buildings along the periphery of some works – an apposite note to strike here, given Fiji’s grim history of indentured Indian labour.

A laying out of Pacific reality, with its natural history as well as its waves of settlement, these works speak of the advent of Christianity and colonial expansion, as they do the complex cultural weavings of Robin’s own Bahá í faith. Above the island/table of communion – where all these influences come together – the birds and butterflies in Living in a material world might embody the ‘winged words’ of the bard/poet/prophet, be it Homer or William Blake (a figure Robin alludes to in Hear the voice) or Bob Dylan. Light falls in and through this space, rendering all the components at once transcendent and bathed in the radiance of this world.

In Robin White’s recent masi we experience the Pacific in terms of that most human of environments, the living room – a place of belief, custom, ritual, sustenance, interaction, rest, activity and, crucially, of love. Instead of thinking about the Pacific as an infinite expanse, here we contemplate it as an intimate family space. Closeness has drawn distance to itself; the evenly spaced waves at a beach have become the lines between floorboards; the ocean’s fish have become the evening’s repast. And, in this space which is at once oceanic and domestic, we question those things that we carry with us – be they material or immaterial – and those that we leave behind.

Gregory O’Brien August 2017

- Quoted in Clare Cavanagh, Osip Mandelstam and the Modernist Creation of Tradition, Princeton University Press 1995

Barkcloth, earth pigments, natural dye

2100 x 3300 mm

Barkcloth, earth pigments, natural dye

2100 x 3300 mm

Barkcloth, earth pigments, natural dye

1000 x 720 mm

Barkcloth, earth pigments, natural dye

1000 x 720 mm