Michael Shepherd

The Land of Cockayne

26 September - 25 October 2014

Painting has always been a compulsive activity for artist Michael Shepherd. The Land of Cockayne, Shepherd’s new series of work, meticulously rendered in the seventeenth century Dutch master’s painting technique, with numerous fine layers of paint and a recessive picture plane, which “is the greatest gift of the Renaissance to world art ” says Shepherd. The artwork, both visually and conceptually compelling, has a cryptic significance beyond that which is immediately visible.

“I was concerned with how imaginative art could deal with social and environmental issues, “ says Shepherd, who is perplexed at the collective amnesia towards the serious impact of ecological imperialism on our social and physical environment. “Northern European settlers’ disregard for the new territories upset the natural balance of our ecological system. This slow but steady “development” of the landscape has essentially changed every major landform in New Zealand: indigenous forests have been denuded, vast acres of swamplands drained and transformed into intensively farmed plains, fragile surfaces eroded and tainted with toxic chemicals, polluted rivers awash with effluent. Sixty percent of indigenous biota are either extinct or endangered and have been replaced by exotic species. We are living in a period of unprecedented change, whereby our man-altered topography has transformed the pattern of peoples’ lives. After a certain time it is the environment that will dictate how we will be able to live on it.”

A scholarly and tenaciously obsessive researcher, Shepherd has, in recent years, befriended and participated in expeditions with botanists, environmentalists and academics. He has also read voraciously across the fields of natural and social history – an experience, which he says, “ has profoundly influenced my thinking. At the same time I felt the purity of the modernist New Zealand landscape in iconic paintings by McCahon, Woollaston, Rita Angus, didn’t factor in the economic, monetized reality. In these new works I wanted to confront these issues, to dig deeper, to have a more profound engagement with the landscape.” In this content-rich series of paintings, Shepherd has de-Romanticized the New Zealand landscape, dramatizing environmental truths with painterly graphic excitement without being didactic or proselytizing.

Shepherd’s two monumental paintings in this exhibition, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (after Bruegel) 2011 and The Land of Leonard Cockayne (after Bruegel ) 2014 have interesting parallels with Pieter Bruegel’s 17th century paintings based on the legends of Icarus and the Land of Cockaigne.

Hubris or over-reaching ambition was the theme of 17th century Dutch master, Pieter Bruegel’s painting, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. In Greek mythology, Icarus is the son of the master craftsman, Daedalus, who is exiled on Crete. Icarus and his father attempt to escape by means of wings that his father constructed from feathers and wax. Daedalus warns Icarus to fly neither too low nor too high, because the sea’s dampness would clog the feathers or the sun’s heat would melt his wings. Icarus ignored instructions, flew too high towards the sun, and the melting wax caused him to plunge headlong into the sea where he drowned. According to different contexts. Icarus’ death may or may not have been witnessed by a ploughman, a shepherd and fisherman.

Like Bruegel, Shepherd’s painting is close to Ovid’s account in Metamorphoses. “Bruegel is a deeply moral painter who has Christianized his iconography, depicting the ploughman as the Sower from the Biblical parable “ you shall reap what you sow”, says Shepherd, whose response to Bruegel’s Icarus’ painting is more a matter of content, the crucial difference being Shepherd’s composition, which is constructed on the Italian proportion of the Golden Section.

Shepherd has used his facility with paint to depict the New Zealand landscape, long renowned and celebrated for its scenic splendour, as a battlefield, furrowed, poisoned and desolate. A menacing plough with two rows of raised tynes, a violent piece of machinery poised to grab and gouge the swampy land, dominates the picture. Icarus’ leg is the only evidence of his headlong plunge into the murky sludge, polluted with cow manure, urine, sour milk and other toxic matter which splatters across the sombre landscape and dying Claudian sky, contaminating the canvas. The sole witness is departing abruptly from the picture as Icarus drowns, a Giacometti figure with his sliver of a leg cut-off at the lower edge of the picture, inverts the suspended leg of Icarus.

American poet, William Carlos Williams’ poem “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” seems prophetic of New Zealand’s lack of awareness or indifference towards environmental damage as we face our own “ Battle of the Somme.”

A splash quite unnoticed

this was

Icarus drowning.

Shepherd’s painting, The Land of Leonard Cockayne (after Bruegel ) 2014 has more formal correspondences in composition with Bruegel’s painting The Land of Cockaigne. The title of the painting and exhibition is a homage to Leonard Cockayne, a brilliant scientist, regarded as the greatest botanist and a founder of modern science in New Zealand.

Cockaigne was a mythical land of plenty, a fictional utopia where idleness and greed were the principal preoccupations. It was a Medieval fantasy of the perfect life “where roasted pigs wander about with knives in their backs to make carving easy, where grilled geese fly directly into one’s mouth, where cooked fish jump out of the water and land at one’s feet. The weather is always mild, the wine flows freely, sex is readily available, and all people enjoy eternal youth.”1

Bruegel’s depiction of Cockaigne shows the spiritual emptiness derived from gluttony and sloth, two of the seven deadly sins. A clerk, a farmer and a soldier lie bloated, sated and asleep beneath a table tied to a tree, laden with partially eaten food. A knight in a lean-to opens his mouth ready for a tart to fly into it and another figure has eaten his way through a mountain of dough to reach this paradise. To reach Cockaigne you have to eat your way to enter.

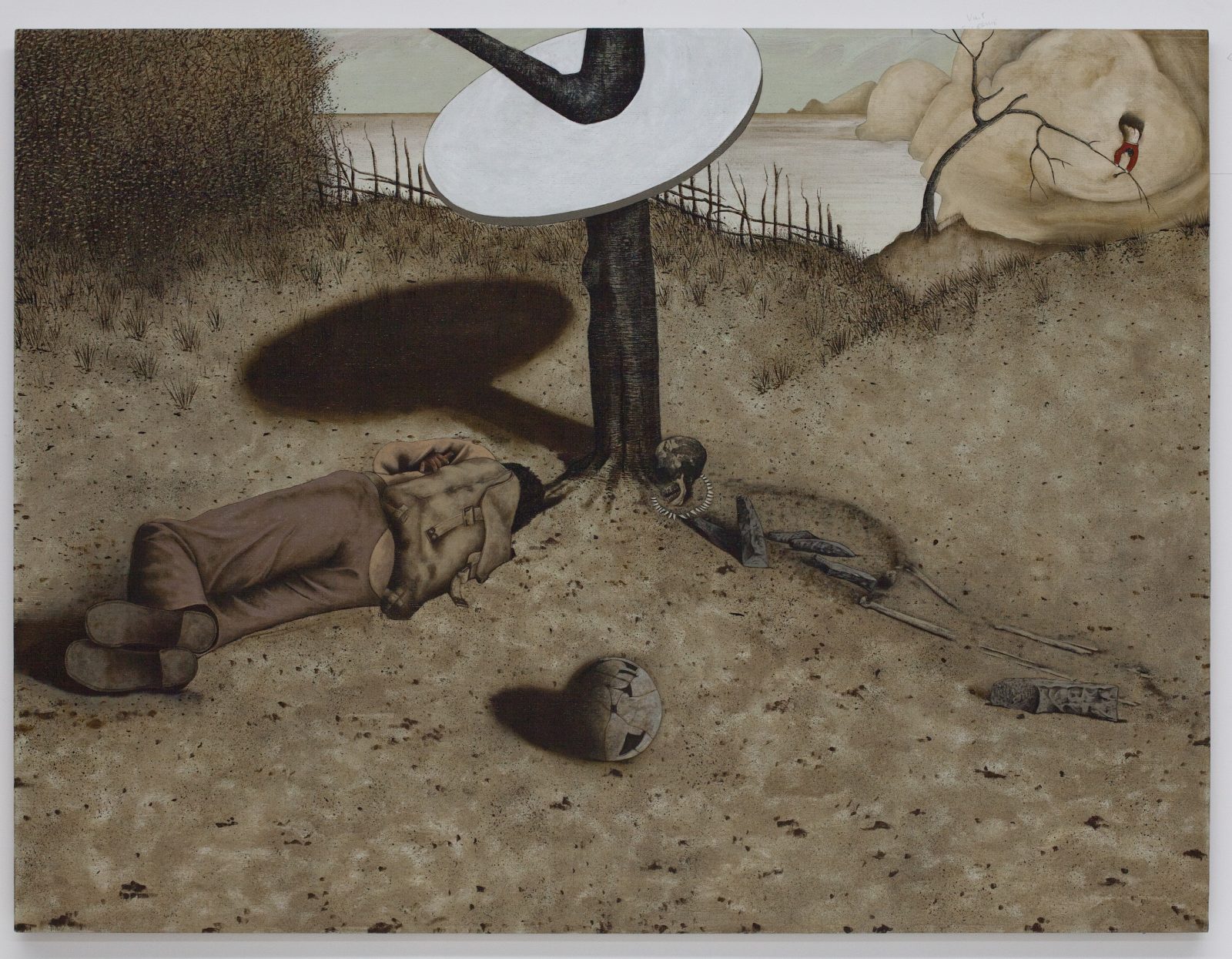

Conversely, Shepherd’s painting consciously parodies Bruegel’s Land of Cockaigne – in this painting a figure has eaten his way into the land of plenty to find the land stripped of vegetation and virtually devoid of life. There is nothing left but death and devastation. A soldier has collapsed beneath a bare table, a skull lies face down below the tree trunk with skeleton bones scattered, and a broken moa egg lies in the foreground. The artist’s limited paint palette of brown and umber reveal a land that is parched and barren, a spindly tree on the foreshore, while a rickety, broken fence runs along the edge of the coastline.

Shepherd’s evocative and hauntingly beautiful paintings have a latent sadness. They deal obliquely with our on-going depredation of the land that cannot be ignored by anyone who cares about people, progress and our planet.

Paula Savage

1. Herman Pleij, Dreaming of Cockaigne: Medieval Fantasies of the Perfect Life (2001):

Acrylic on board

850 x 1040 mm

Acrylic on board

1190 x 1580 mm

Acrylic on board

900 x 1200 mm

acrylic on board

735 x 1020 mm

acrylic on board

1170 x 1865 mm