Elizabeth Thomson

White Coda Blue Coda

16 March - 27 April 2018

Blue notes, white noise

It is proportion that beautifies everything, the whole universe consists of it and music is measured by it. – Orlando Gibbons (1583–1625)

Ours is a universe of moving parts, of flickering, wavering, trembling movement. Things circulate; they increase and then diminish. They ebb and flow, surge and subside, glimmer and fade and are replenished. This is also the dynamic in Elizabeth Thomson’s art, which marries a life-long fascination with science and an artistic concept based more upon the processes of nature than its static forms.

When looking at Thomson’s work, the viewer is often unsure of what it is they are encountering: rock pool or lime deposit, ocean floor or the skin of an onion. As a meditation upon, and response to, the whelming natural world, her art is conceptually far closer to the process-based art of Len Lye than, say, to Colin McCahon’s metaphysical landforms. You could say Thomson’s allegiance is more with the verb than the noun.

Incorporating microscopic images, as well as views through a telescope, Thomson’s art proposes that nature is made up, in a variety of fundamental ways, of what we are not able to see. What her works offer are traces, momentary impressions or reflections. In their stylised reconfiguration of mineral and plant materials, her artistic project has a notable precedent in the photographs of Theo Schoon, who found inspiration in some of the same central North Island geothermal sites that Thomson has explored in her current and previous exhibitions. A case in point, Waiotapu (‘sacred water’) is based on an encounter with the well-known thermal field south of Rotorua. The Tatio works take, as their starting point, the geothermal regions of New Zealand and Chile (El Tatio is a world-renowned Chilean geyser field which the artist visited and photographed in 2013). ‘I don’t necessarily use photographs of a particular place,’ she elaborates. Most of the time the works are, in her mind, ‘closer to allusion than recollection’. Yet their origin in a specific place is integral and the originating sites are often retained in the works’ titles: Valle de la Luna references another well-known Chilean geological area of petrified salt and sand. Laguna Miscanti alludes to a heart-shaped lake, famously bright blue, in northern Chile.

As Thomson herself has said, the works are

about exploration and supposition –knowledge, memory, instinct, projection, the state between sleeping / waking, the real and the hypothetical. It’s about looking at the detail of life – microscopic / cosmic etc but also looking back in time to the beginning or a virtual state of being, uploaded into the conscious. It concerns the sensation and experience of viewing.

With similar objectives in mind, British painter Bridget Riley once wrote of her desire to capture ‘tremor’, to ‘shimmer like a tree in the wind’. In regard to her op art paintings of the 1960s, Riley would speak of ‘rapidity’, ‘shift’, ‘a fluttering sensation’, and her desire to establish a ‘shiver’ in a work. The kind of multidirectional, multidimensional movement you find in Thomson’s work – a current or disturbance – is what Riley called a sense of ‘rise’, both within and across the surface of a work. (The British painter considered the effect far closer to Seurat or Monet than to the slick, metropolitan surfaces with which her art was too often associated.)

With their rhythmical interludes and microtonal variations, Thomson’s works also have at their heart a musical concept. In music, variations are a kind of repetition in which only some elements are repeated while others are developed or altered. Thomson’s Kind of Blue references Miles Davis’s epoch-defining recording of that title – famous for its nuanced interplay of both musical and ‘real’ time. The title of Thomson’s Freedom and Structure, Light & Waves II hints at this theme/variation approach.

Thomson’s works belong to what Joanna Margaret Paul once called ‘the musical Frances Hodgkins school’ in New Zealand art (a school which would also count among its members Gretchen Albrecht, Paul herself and, more recently, younger artists who use repetition and pattern such as Selina Foote and Kathy Barry). Importantly Thomson’s musicality leads the viewer back to the natural world – to the white noise of wind and ocean, as well as the patterned sand and mineral deposits which configure in her mind as musical notations.

It is a very sensory kind of immersion that Elizabeth Thomson’s work offers – as if the viewer’s optical nerve went beyond the human brain and continued through the body. Which leads to another major point of departure in relation to her art and the pictorial tradition, which has for centuries, been integral to humanity’s relationship with the natural world. The western tradition is one fundamentally based upon a sense of being found, anchored to the real, a state of knowing where you are. Departing radically from this model, Thomson’s art offers an experience of being untethered and set adrift. Without an articulated focal point, the entire surface of the work becomes the centre of focus. Viewers find themselves moving simultaneously outwards into the world, and inwards into the realm of sensation. With its blue notes and white noise, Thomson’s art is a coda, the after-glow or after-impression of an encounter with nature. But the works are never an endpoint; rather they are moments of continuance, evolution, an on-going music of the visible.

– Gregory O’Brien

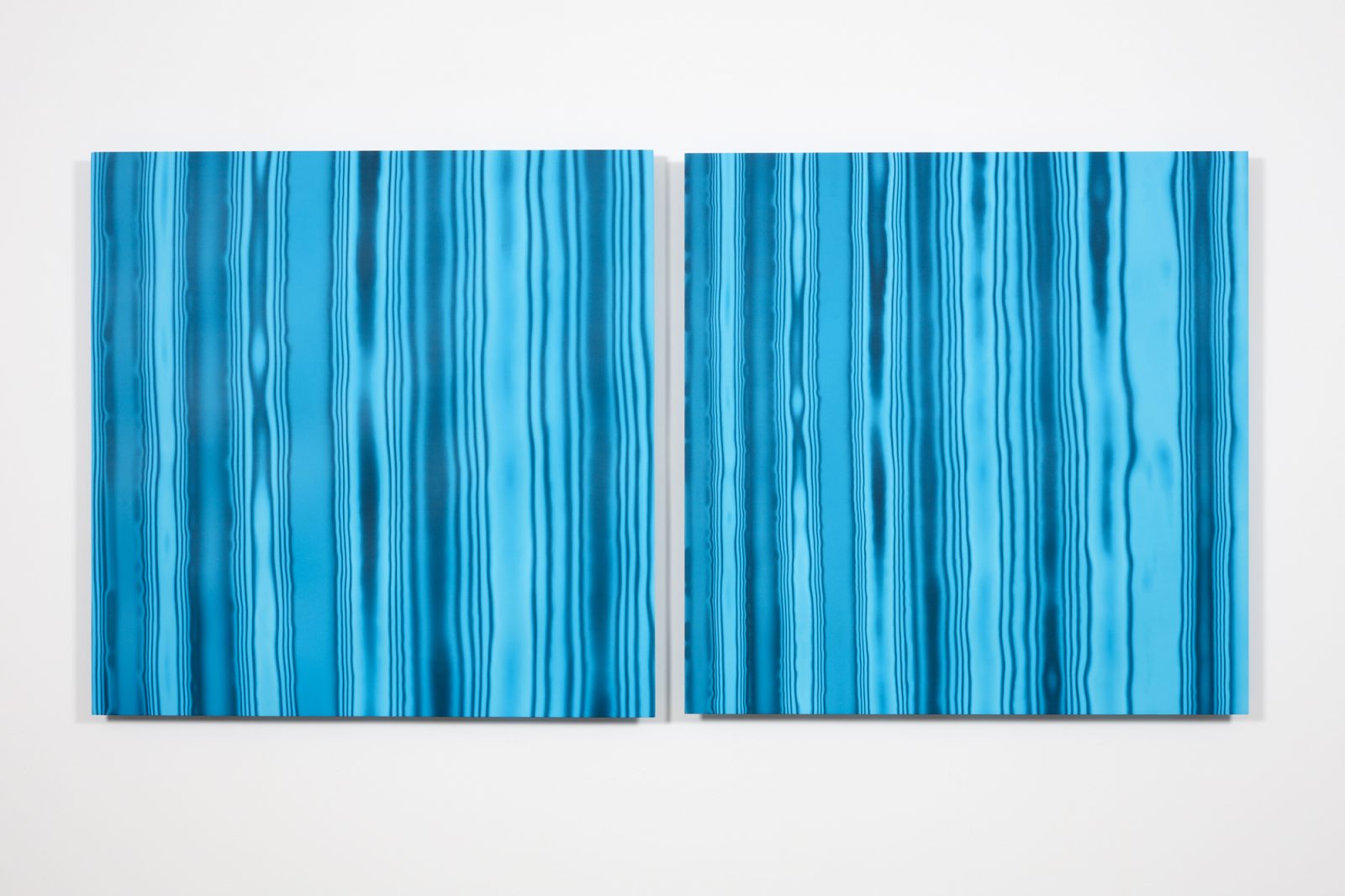

Nylon fibre, cast vinyl film, lacquer on contoured and shaped wood panel

755 x 755 x 50 mm

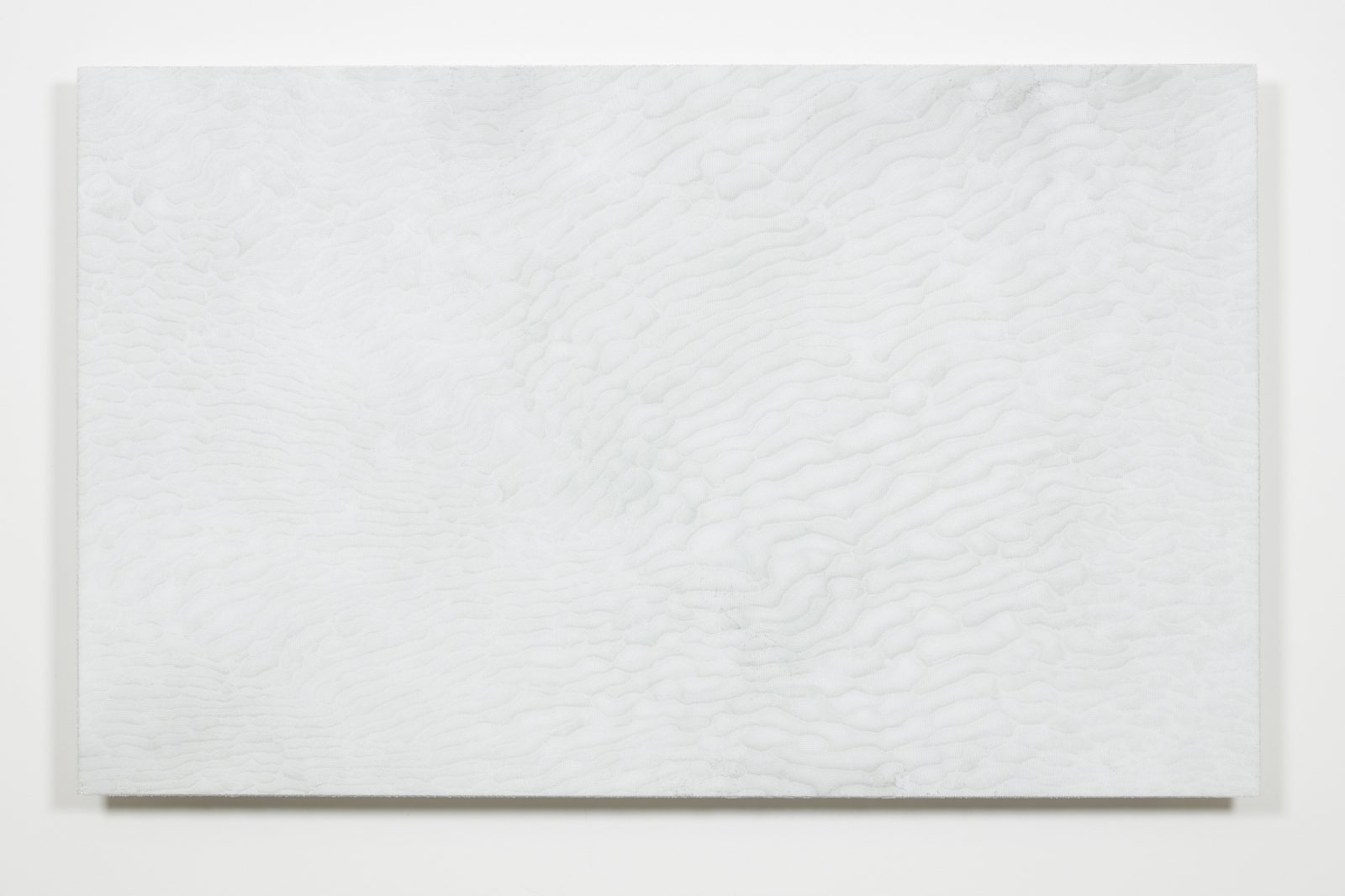

glass spheres, optically clear epoxy resin, cast vinyl film and lacquer on contoured wood panel

755 x 1222 x 40 mm

glass spheres, optically clear epoxy resin, cast vinyl film and lacquer on contoured wood panel

755 x 1222 x 40 mm

glass spheres, optically clear epoxy resin, cast vinyl film and lacquer on contoured wood panel

755 x 1222 x 40 mm

glass spheres, optically clear epoxy resin, acrylic, cast vinyl film and lacquer on panel

1400 x 1400 x 50 mm

glass spheres, optically clear epoxy resin, cast vinyl film and lacquer on contoured wood panel

755 x 755 x 40mm

cast vinyl film, lacquer on contoured and shaped wood panel

1400 x 1400 x 50 mm

cast vinyl film, lacquer on contoured and shaped wood panel

120 x 1120 x 50 mm each panel